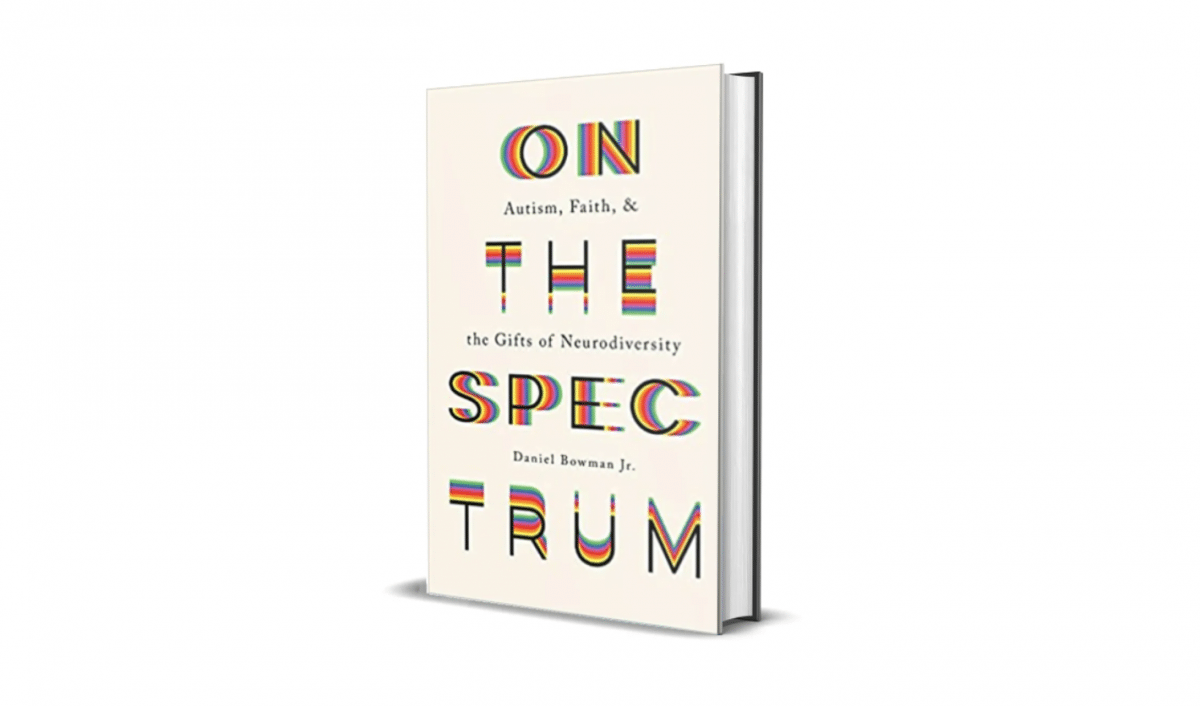

ON THE SPECTRUM: Autism, Faith, and the Gifts of Neurodiversity. By Daniel Bowman, Jr. Grand Rapids: Brazos Press, 2021. Xxxi + 221 pages.

I offer here an updated version of a review I posted on my blog—Ponderings on a Faith Journey—in October 2021 of Daniel Bowman’s excellent book On the Spectrum: Autism, Faith, and the Gifts of Neurodiversity. The reason for offering an updated version of the review is that the Academy of Parish Clergy has chosen to honor the book as its 2022 Book of the Year (chosen from books published in 2021). I serve as the chair of the committee that made the selection. We had the opportunity to announce our Book of the Year Award, along with a Top 10 list of books, in a Zoom conversation simulcast on the APC Facebook page. Before COVID, we would have announced the awards at our annual conference, but COVID required a different format—Zoom plus Facebook. While the Academy looks for books that will speak to clergy, this is a book that speaks to a very wide audience.

In recent years we have heard quite a bit about autism. It became the cause célèbre of anti-vaxxers who blamed the rise in diagnoses of autism on increased vaccinations. Most reports on autism suggested that it is a disorder that needs a cure. When people think of autism, they often think of one particular form—Tourette’s Syndrome—or they think of the movie Rain Man. What if, however, autism isn’t what we thought? I will confess that I know little about it, even though I have clergy friends and colleagues who self-identify as autistic. With as much conversation that is out there in the larger society, with much misinformation being promulgated, it would seem that now is the time to start paying attention and learning the facts.

Robert D. Cornwall

I hadn’t intended to explore or reflect on autism until I received an advanced reader’s copy of Daniel Bowman’s book On the Spectrum. Even then I simply put it on my review stack. Since it was originally sent to me in my position as a journal editor, I could easily pass it on to another reviewer. I thought seriously of asking one of my clergy colleagues who is autistic to review it. Then, before I reached out and made that contact, I saw a note from a clergy colleague and writer whom I respect, who recommended it. With Katherine’s recommendation in mind, I decided to open the book to see what I might find. I must say that I am glad I decided to read the book. I quickly realized that I know very little about autism. While I knew that autism existed on a spectrum with different degrees of effects, beyond that, I knew very little. As I read Bowman’s book, I realized that this is a book that needs to be read by everyone, and not just autistic persons or the family members of autistic persons.

Books come in different forms. There are clinical and scientific books that are important and helpful to a point. Then there are the memoirs, most of which are written by parents of autistic children sharing the challenges of parenting an autistic child. Very few if any books on autism have been written by autistic adults, sharing their stories. That is until Daniel Bowman wrote On the Spectrum, which allows us to hear a first-person telling of the story of autism from the perspective of one who was diagnosed as autistic.

Bowman is a college professor who teaches creative writing and the arts at Taylor University in Upland, Indiana. He also codirects the university’s “Making Literature Conference.” The key here is that Bowman is not a math and science whiz, he’s a professor in the humanities. That might be surprising to some. As I noted he is one of the few autistic persons who has written a memoir about living as an adult who is autistic. As I also noted above, most books on autism are either written by scientists and clinicians or parents of autistic children who share the challenges of raising a child who is autistic. He hopes that by writing this book he can pave a way for others to share their stories.

When it comes to autism, language and nomenclature are important. Bowman writes that there is disagreement within the autistic community as to whether we should speak of a person living with autism or speak of a person as being autistic. The former suggests the possibility that autism is a disorder that can be overcome/cured. That is, it suggests that autism is an abnormality. By choosing to identify as an autistic person, Bowman tells us that this is his identity. This is who he is. What differentiates him as a neurodiverse person from a neurotypical person is the different operating systems with which we live. Think of the difference between Apple and Microsoft.

The book contains twenty-five essays that explore different elements of life. Some of these essays speak directly to autism while in others it is not the central focus but is present. He prefaces the book with a chapter he titles “Prelude: You Always Hurt the Ones You Love: Crisis, Diagnosis, Hope. It is in this introduction that Bowman sets a context for us as the reader. He gives us a basic overview of his life story and his journey toward diagnosis and making sense of that diagnosis. As for the twenty-five essays, he breaks them into seven sections.

The first section is titled Foundations. As the title of the section suggests, the essays in this section offer definitions and set the tone for what is to come. In the essay titled “Why You Should Read This Book (and How),” an essay directed to folks who are neurotypical, Bowman emphasizes the importance of hearing from autistic writers. Too often those who are not autistic speak for those who are autistic. He makes it clear that neurodiverse persons can speak for themselves. He writes as well that “every essay in the book is thoroughly autistic!” So, he warns against “skipping ahead to the ‘more autistic’ parts of the book. So, what he does is invite us to “inhabit the whole story—and see the autistic heart, mind, body, and spirit at work in both the profound and the mundane” (p. 5). Here the key to the conversation is the distinction between neurodiversity and being neurotypical (I had never thought of myself as neurotypical, and yet I am. That is my operating system).

From the section on foundations, we move to a section titled “Place.” Here again, it’s important to understand this is a collection of essays, which are, as he says, fully autistic even if autism isn’t front and center. So, in this section, we explore the place—where he lives and breathes. We explore culture making in the context of, for example, an effort to create a county arts center in his community. He shares how difficult it was for him to enter into this work because his operating system makes working with others at times difficult. He also writes about riding his bike and how that fits into his life as an autistic person.

The next section speaks to “Community, Worship, and Service.” The essays here don’t simply speak to church life, but the church is an important component of this section. It’s important to remember that this is a book written not only from an autistic perspective but a faith one as well. It speaks to the challenges of being in a community when social interaction is difficult. Indeed, when service is a challenge. One thing he shares is the challenge of spontaneity. He needs a heads up before entering into an experience, thus for him, the formality of the Episcopal Church is extremely helpful. The point is that the way an autistic person worships and serves might be different from a neuro-typical person.

From church life, we move to his vocational life. Here he shares about his life as a writer, including his attraction to poetry. He writes about the “Insidious Nature of Bad Christian Stories.” He has a problem with bad writing, such as the kitsch that often is offered in the form of Christian novels. He writes that “Bad storytelling is bad theology, forwarding an immature view of God, self, and neighbor. And in my case as a creative writing professor, failing to call out bad storytelling is also bad teaching” (p. 111). This section speaks to the role that autism plays in his life, but as you can see it is a broader conversation, but from a particular perspective informed by his identity.

The next section takes up questions of family and identity. He talks about his family name and what it means. He invites us to explore our own identity, including ancestry. In the course of this conversation, he shares how his diagnosis helped him learn what makes him tick. So, he writes “I came to know that the constellation of traits I displayed had a name: autism—and that taking on the name autistic, while scary, could also be redemptive. In the end, it’s about being my true self” (p. 148). In the section that follows he includes three interviews that speak to his life as an autistic person. He notes that these interviews were not oral but involved questions to which he could write answers. He does this to show the importance of speaking about what it means to be autistic. He sees his own calling as involving sharing his perspective, his voice so that others might come to understand their own identity. This takes a lot of courage but is so important.

Bowman concludes the book with a section titled “New Directions.” He speaks about how autism is represented in plays, books, novels, and films. He addresses the fact that too often these portrayals are developed by non-autistic persons. They attempt to speak about what they have not experienced, and even if well-meaning often get the message wrong. So, Bowman is calling here for those who wish to share the story of autism and neurodiversity to include those who are neurodiverse. Yes, some cannot communicate, but that is only one portion of the spectrum. There are many like Bowman who are fully capable of speaking for themselves.

Bowman writes with great passion about his own journey of discovery and what it means for him to be autistic. He recognizes that it would be much easier to be a neurotypical person, but that is not who he is. Thus, he has to find his own pathway. He writes the book in part for people like me so we can know what it means to be autistic in all its diversity—not all autistic persons are great with math (i.e., Temple Grandin and Rain Man). Some, like Bowman, are gifted artists and writers, though the way they write will be different (different operating systems). He also writes with the intent to be a mentor to others who are autistic, helping them to discover their own gifts and way of living.

As I read Daniel Bowman’s On the Spectrum and considered the definitions and descriptions, I began to better understand what it means to be autistic. It also gave me greater insight into how my autistic friends live their lives. I also began to realize that I may have other friends and family members who are autistic, and they may not know it (and at least I do not). What a gift this book is to the church and the larger world. It is important that autistic people tell their own stories, rather than letting neurotypical people (like me) define them and their stories. While autism is part of every essay, it is not always the focal point. That is part of the point of the book. Autism needn’t be at the front of the conversation in every case for us to learn about it. So, take and read. Thanks must go to Katherine for raising the book to the forefront of my attention! I hope I have done the same for you.

This review originally appeared on BobCornwall.com.

Robert D. Cornwall is an ordained minister in the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ). Now retired from his ministry at Central Woodward Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) of Troy, Michigan, he serves as Minister-at-Large in Troy. He holds a Ph.D. in Historical Theology from Fuller Theological Seminary and is the author of numerous books including his latest books: Called to Bless: Finding Hope by Reclaiming Our Spiritual Roots (Cascade Books, 2021) and Unfettered Spirit: Spiritual Gifts for the New Great Awakening, 2nd Edition, (Energion Publications, 2021). His blog Ponderings on a Faith Journey can be found at www.bobcornwall.com.