“I believe this notion of the separation of church and state was the figment of some infidel’s imagination.”

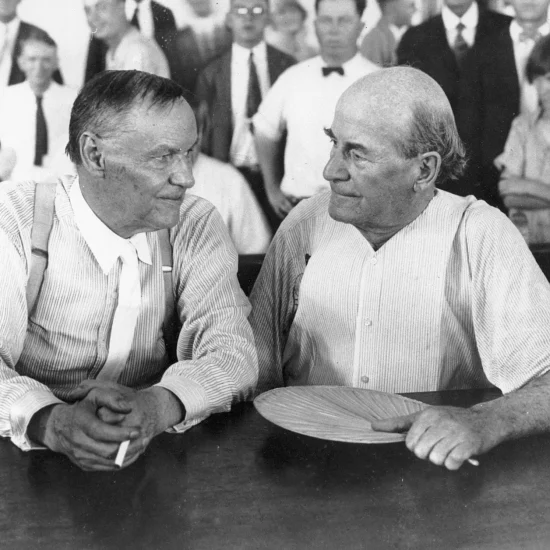

With that declaration, the pastor of First Baptist Church in Dallas, Texas, defended his partisan campaigning for Ronald Reagan in 1984. In his sermon on the eve of the Republican National Convention in Dallas, W.A. Criswell, who was also a former president of the Southern Baptist Convention, implicitly endorsed Reagan’s reelection. From the pulpit, Criswell praised Reagan as “the best president we ever had.” Then a few days later Criswell offered the benediction at the Republican gathering on the night Reagan gave his acceptance address for his renomination.

CBS Evening News asked Criswell how he justified his politicking from the pulpit of First Baptist and the podium of the RNC in light of the separation of church and state. That’s when he blamed an unnamed infidel for the concept. We’re not sure which one. Perhaps he meant Thomas Jefferson (who did cut up his New Testament), but the author of the Declaration of Independence borrowed that concept of church-state separation from Baptists like Roger Williams, John Leland, and Thomas Helwys.

Yet, as Criswell played a significant role in the movement that was at that moment pushing the nation’s largest Protestant denomination rightward and into more active partisan politics, he needed to excommunicate those historic Baptist figures. After all, the constitutional principle that most stands in the way of the agenda of Christian Nationalism is the idea of church-state separation, especially as articulated in the First Amendment clause barring government establishment of religion.

But the phrase “separation of church and state” isn’t in the Constitution, someone might interject. And by someone we mean lots of critics of the idea today. It’s a true comment but not a clever one. That exact phrase cannot be found in the Constitution, but that doesn’t mean it’s not a constitutional principle. You also won’t find the phrase “religious liberty” in the document either, but it’s clearly a constitutional precept. Similarly, you won’t find the word “trinity” in the Bible, but that doesn’t mean it’s not a biblical doctrine.

Because of the impact of church-state separation on our society, there’s been a significant political effort to chip away at the wall between the two. The perspective of Criswell appears to be gaining traction not only within his denomination, but also with Christians more broadly and even with justices on the U.S. Supreme Court.

On Tuesday (June 21), the latest shot came as six justices ruled in Carson v. Makin to push state funding of private religious schools. As we consider the problematic ruling and how it shifts First Amendment jurisprudence, we should also revisit the case that seems to most energize the effort to undo church-state separation. After all, the 60th anniversary of the Court’s landmark decision on government prayers in public school will be this Saturday (June 25). Six decades later, the high court has moved substantially toward the perspective of Christian Nationalism (with one justice even dismissing the “so-called” separation of church and state).

In this issue of A Public Witness, we travel back to 1962 to consider the Court’s case on prayer in public schools (including how Word&Way and other Christians praised the ruling at the time). Then we return to the present to analyze the arguments in Carson v. Makin before peering into the future to consider where this dangerous trip might be taking us as a nation.

In this issue of A Public Witness, we travel back to 1962 to consider the Court’s case on prayer in public schools (including how Word&Way and other Christians praised the ruling at the time). Then we return to the present to analyze the arguments in Carson v. Makin before peering into the future to consider where this dangerous trip might be taking us as a nation.

NOTE: The rest of this piece is only available to paid subscribers of the Word&Way e-newsletter A Public Witness. Subscribe today to read this essay and all previous issues, and receive future ones in your inbox.