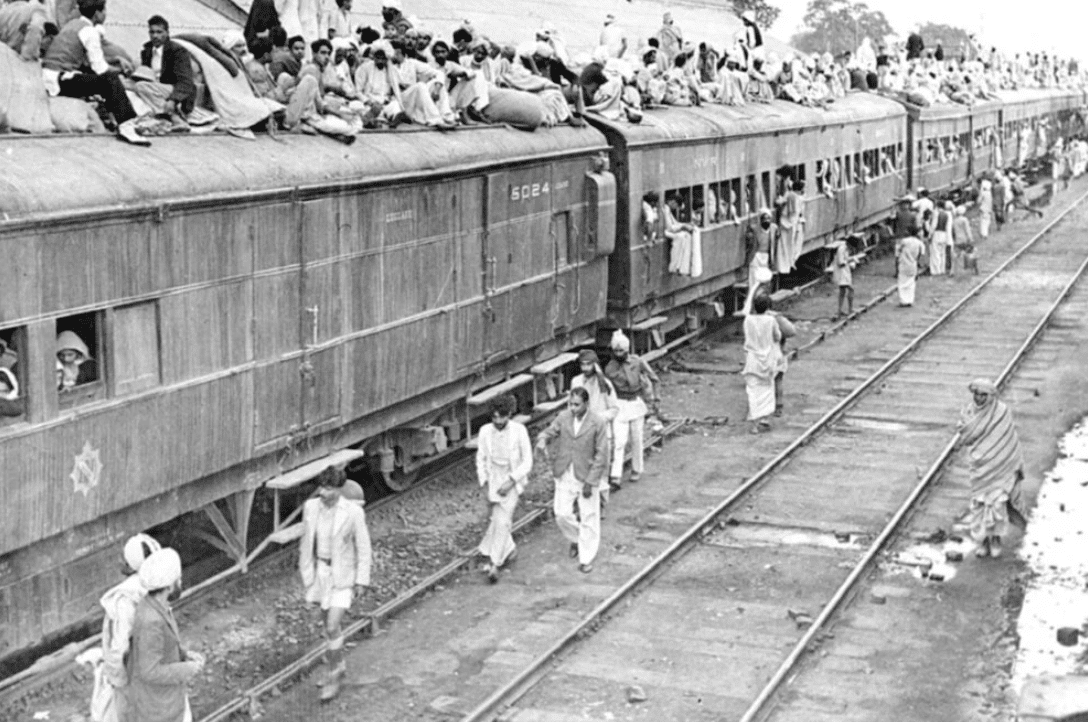

A special refugee train at Ambala Station in February 1954 in northern India. The 1947 Partition of India resulted in the largest human migration in history, lasting years. Photo courtesy of Creative Commons

(RNS) — In September of 1947, after Tarunjit Singh Butalia’s Sikh grandparents’ ancestral home in West Punjab was set afire by mobs from a neighboring village, they had no choice but to flee. A Muslim couple in present-day Pakistan swore on the Quran to give them shelter and protect them as if they were family.

They survived, and seven decades later, Butalia, now executive director of the interfaith advocacy organization Religions for Peace USA, tracked down the Muslim couple’s son. The man guided him to the village where his parents, Ahmed Bashir Virk and his wife, Amina Bibi, were buried. Butalia knelt and kissed their graves.

“There are angels that walk on the earth,” said Butalia, who chronicled his grandparents’ past in his 2020 book, “My Journey Home: Going Back to Lehnda Punjab.” “And for my family, they were indeed angels on earth.”

Butalia is only two generations removed from the Partition of South Asia in August 1947, when the British, as they ended their colonial rule in India, imposed a national boundary across northern India that created Pakistan. In so doing they split the religiously diverse province of Punjab into West, or Lehnda, Punjab, and East, or Charda, Punjab.

The border added a geographical quotient to the existing religious distinctions made between Sikhs, Muslims, Hindus, Jains and Christians, resulting in nearly 15 million people being divided from their religious community. Many left their homes to seek wholeness again in the largest mass migration that the region has seen; others stayed and fought for their rights as minorities. More than half a million people died in revenge killings, riots and communal violence from all sides.

Butalia believes the kindness shown to his grandparents fostered his devotion to creating meaningful relationships and understanding between people of faith. The shared history of Muslims, Sikhs and Hindus at the time of Partition led him to his current position, as well as his work as a founding member of the Sikh Coalition for Interfaith Relations.

“The interfaith movement is very much who I am,” said Butalia. “It has been a critical factor in my formation of Sikh identity.”

The feuding that the Partition initiated between Indian and Pakistani Hindus and Muslims has not ceased. Increasingly it is fueled by governments on both sides that stoke religious nationalist feelings among their citizens.

But in this 75th anniversary year of the Partition, stories such as Butalia’s are the focus of many Indians and Pakistanis who are looking to oral history to preserve the memory of interfaith collaboration as an essential part of their two countries’ histories. Butalia himself said he hopes to use the past, when Hindus, Muslims and Sikh protected each other, to look forward past what he calls a pervasive “patriotism of hate.”

At a recent webinar about the Partition of Punjab held by the Sikh Council for Interfaith Relations, three scholars — one Hindu, one Muslim and one Sikh — related their families’ experiences.

One speaker lived through the trauma himself.

“The Partition of Punjab was a period of marked madness, massacres and lifelong misery,” said Ranbir Singh Sandhu, professor emeritus at the Ohio State University. “But goodness eventually prevails, and it did this time too.”

A practicing Sikh, Sandhu was an engineering college student in east Punjab in 1947. The neighborhood where he lived at the time was declared a Muslim refugee camp after the Partition, which had rendered his Sikh family the minority religious group. But that didn’t stop them from providing the refugees with halal food and temporary shelter.

“These were old neighbors and helpers,” said Sandhu. “We knew they were friends.”

When he and his brother were forced to leave what is now Lahore, Pakistan, it was a group of Muslim men that helped them find their way. And when heavy rains in Punjab damaged houses, Sandhu’s Muslim friends took charge of the rescue.

Like Butalia, Sandhu continued to maintain friendships with Muslims, Hindus and Christians, whether as colleagues or as Ph.D. students he advised.

“All this madness and misery was avoidable,” said Sandhu. “Both nations have wasted a lot of money on fighting.”

The webinar drew floods of comments from audience members that showcased the wide array of stories that Punjabis across the world still tell. The panelists agreed that the best way to share anecdotes and tales of the Partition is through social media, or what another panelist, Akhtar Hussain Sandhu, called “the new face of Punjab nationalism.”

The 1947 Partition Archive, founded in 2013, is dedicated to preserving stories from the South Asian community. Panelist Munish Singh is the moderator for the Punjab Heritage Facebook group, which has over 100,000 members.

We must use these tools to do what the government can’t provide,” said Singh. “Cross-border, people-to-people conversations.”

For the divisions to heal, Butalia said, people must separate neighbors from the actions of their governments, confront people in their own religious communities who are moving toward extremism and use compassion generously.

“What worries me is the line that people have drawn in their hearts,” said Butalia. “That is the border that needs to be erased.”

In his book, Butalia shares a story from his visit to the hometown of Guru Nanak, the founder of Sikhism, who was famously accompanied on his journeys by his Muslim friend Bhai Mardana. Butalia recalled seeing a group of Muslim schoolchildren visiting the gurdwara, as Sikh houses of worship are called.

The students told him they often come by for the langar — the free meals offered by gurdwaras as a service to their community. To his surprise and delight, the children told Butalia that they exchanged Facebook and Twitter accounts with the Sikh children from the other side.

“That is the future,” said Butalia. “This change is already happening. We just need to amplify it.”