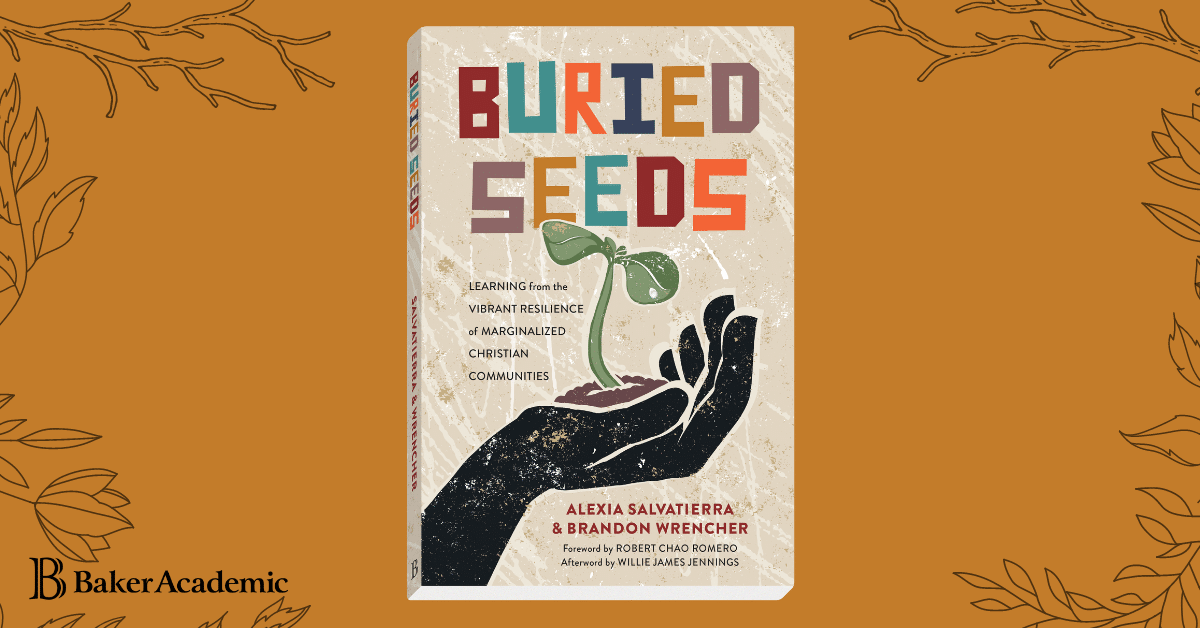

BURIED SEEDS: Learning from the Vibrant Resilience of Marginalized Christian Communities. By Alexia Salvatierra & Brandon Wrencher. Foreword by Robert Chao Romero. Afterword by Willie James Jennings. Grand Rapids, MI: BakerAcademic, 2022. X + 245 pages.

What might the church at large learn from marginalized Christian communities? At a time when many question the relevance of traditional institutional structures, this is a pertinent question. Many marginalized Christian communities live without the traditional trappings of institutional religion. Nevertheless, they often thrive, and many take the lead in lifting up those on the margins so that they too might thrive. Part of their witness has to do with resilience. So, perhaps there is much for the churches that live within institutional structures to learn from these communities.

Robert D. Cornwall

Alexia Salvatierra and Brandon Wrencher invite us to consider the witness of two forms of Christian community, one that emerged in Latin America and the other within the American slave experience, suggesting that these communities reveal something about how God is present in the most difficult of situations. They offer this word to us in Buried Seeds. The buried seeds they speak of are present in and through the Basic Ecclesial Communities of Latin America and the Hush Harbors that emerged within the American slave context, the latter being communities that stood outside the institutional forms of Christianity offered by slave owners as a way of controlling their property. The two authors have explored, experienced, and witnessed how these two types of community exist and can help provide us with guidance as we navigate an uncertain future while recognizing God’s commitment to justice for those who experience the margins.

I first encountered Alexia Salvatierra through her book co-written with Peter Heltzel—Faith-Rooted Organizing: Mobilizing the Church in Service to the World. I read that book at a time during my tenure helping form and lead a local faith-based community organizing effort. We found this earlier book to be uniquely helpful as it helped further root our organizing efforts in our faith communities. We see some of that effort present in Buried Seeds. Salvatierra, who has long been involved in the intersection of faith and immigrant justice, currently serves as the academic dean of Centro Latino and as a faculty member at Fuller Theological Seminary, teaching in the area of integral mission and global transformation. As for her co-author, Brandon Wrencher, this is my first encounter with him. Wrencher serves as pastor of Blackburns’ Chapel United Methodist Church and director of The Blackburn House in Todd, N.C. He is also active in the Christian Community Development Association, editing their journal.

Salvatierra and Wrencher layer the book by sharing insights from two movements that emerged within marginal communities and were led by folks from within those communities. Salvatierra focuses on the Basic Ecclesial Communities (BEC or CEB), which emerged within the Roman Catholic church in Latin America and the Philippines. They are aligned to some extent with Liberation Theology. They tend to be small group ministries, led by group members who gather to study scripture and then make applications to their social conditions. These are small group gatherings that have not always had the support of the institutional church, in large part because they often found themselves at odds with conservative governments. Perhaps the best-known expression of the BECs is the communities that emerged in Nicaragua in the 1970s. The reflections on the Scriptures were gathered together by Ernesto Cardenal in the Gospel of Solentiname, a text the authors draw upon in Buried Seeds. The Hush Harbors, the communities that Wrencher lifts up, were gatherings of slaves who met clandestinely so that they might worship outside the eyes of the plantation owners. These gatherings were also lay-led/group-led efforts. They also served in many cases as the starting place for organizing the escapes of slaves from their bondage.

As the two authors explore the witness of these two movements, they focus on five key themes: kinship, leader-full, consciousness, spirit-uality, and faith-full organizing. They use their reflections on these themes to show how “these principles and practices” are used “to cultivate vibrant, resilient, integral Christian communities led by marginalized people” (p. 4). They utilize the methodology of conscientization, an educational method that has roots in the work of Brazilian educator Paulo Freire. This method involves three steps – ver (to see), juzar (to judge/interpret), and actuar (to act on what is understood). Since participants come from different points of privilege, they use three biblical personages throughout to reflect these differences. Thus, in the course of the book, we hear from the perspective of Lydia (a businesswoman who uses her power to support the ministry), Amos (a shepherd/prophet emerging out of the marginalized community), and Ruth (a migrant). These voices help connect our faith story to the organizing efforts described in the book.

The first chapter is devoted to introducing the reader to the Basic Ecclesial Communities as they emerged in Latin America and the Philippines. This is the area of expertise/experience of Salvatierra. Though the influence and presence of the BECs have faded somewhat in their influence and presence, the authors note that they “represented an unprecedented level of engagement by poor and marginalized people as protagonists in their common spiritual and social lives” (p. 28). Then in chapter two, the authors introduce us to Hush Harbors, a movement I am less familiar with, but which had an important impact on the lives of enslaved persons who experienced not only marginalization but faced dehumanizing realities at the hands of slave owners. Wrencher, who writes this chapter, notes that Hush Harbors offer hope to Black communities that are experiencing the decline of the institutional Black churches. He notes that “Hush Harbors persist where Black people’s spirits and bodies are unbound, unbought, and unbossed!” (p. 47).

Having introduced us to these two movements, the authors then move on to their five themes, giving each theme a chapter of its own. The first theme is kinship. That is, a sense of family or community. The authors go into great detail regarding what this looks like, but ultimately, they reach the conclusion that we’re all kin, so we can either be a healthy family or a dysfunctional one. As such, BECs and hush harbors give us a compelling picture of living into that kinship in ways that enable liberation” (p. 85). As noted above, both movements were largely lay/group-led. They had little or no connection to institutional religious communities. Thus, the community itself provides the leaders. In fact, the community itself is filled with leaders even if those leadership roles remain undefined.

Chapter five introduces the reader to Conscientizacíon or consciousness-raising. As these communities reflected on their faith, they were provided with a lens to examine their context, such that they could begin the process of liberation. In chapter 6, the authors answer the charge that these efforts are social movements but not spiritual ones. Thus, they emphasize here the role of the Holy Spirit by dividing the syllables of the word spirituality. They show us how these two movements, which are in many ways very different, “both rest on a vibrant embodiment of faith. The heart of the word incarnational (incarnatio in Latin) is caro, meaning ‘flesh.’ Because the BECS and hush harbors were about the Word going deep into the flesh. Whether we are reflecting on the dancing and moaning of the hush harbors or the prophetic dramas of the BEC reconciliation practices, we are examining a multisensory experience of a God who is vividly present in every aspect of daily life” (pp. 159-160). The final theme is faith-full organizing. Everything we’ve read leads to this point where faith is put into action. These actions take many forms depending on the context, but in the end, people are organized to act on their faith to transform society.

The authors conclude the book with a chapter titled “Catch the Fire.” In this chapter the authors two contemporary communities that exemplify the themes we’ve encountered earlier in the book. One of these communities is a Latinx community, while the other comes out of the African American context. They walk through each of the five themes, showing how these communities give witness to those themes as they “fight for justice in the public square.” Leaders of both communities are given space to describe their ministry efforts. In his afterword to the book, Willie James Jennings takes us to the Book of Acts, and reflecting on the experiences shared there, asks the question of place. He asks the question of what means to become a place where people can gather to envision and implement “new possibilities of thriving life together even in, especially in, confined and confining spaces” (p. 222). That last thought takes into consideration the realities of the COVID pandemic.

So, he invites us to consider the message of the two authors, asking an important question for our time: “We who name the name of Jesus are all faced with a decision that grows in urgency with each passing day, whether we will live in places in ways that are inconsequential to the gospel we say guides our lives or whether we will root ourselves in a place and decide to become people whose very name becomes synonymous with a meeting and with a thriving together that others never thought possible” (p. 223). This is an important question that our authors help us think through and implement.

Having read widely through the years the works of Liberation Theologians, including works that explore the BECs, that effort is well known to me. I was not as aware of the Hush Harbor tradition, at least by that name, but the authors provide the reader with important introductions to both movements as well as guidance that can help invigorate the larger church as we listen to the voices of those on the margins. The critics of these movements charge them with being more political than religious, but as we see here, the religious has political implications, especially if one is living in a marginalized context. It’s easy to separate religion and politics when one is living in affluence. It’s less possible when you live on the margins. Unlike Christian nationalism, these movements invite us not to control others but to find liberation. Thus, this is not just a book for those who live in marginalized communities. Buried Seeds is a book that offers a witness to the whole church that it might find new paths to live out the Gospel. Thus, this is a worthwhile book to explore.

This review originally appeared on BobCornwall.com.

Robert D. Cornwall is an ordained minister in the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ). Now retired from his ministry at Central Woodward Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) of Troy, Michigan, he serves as Minister-at-Large in Troy. He holds a Ph.D. in Historical Theology from Fuller Theological Seminary and is the author of numerous books including his latest books: Called to Bless: Finding Hope by Reclaiming Our Spiritual Roots (Cascade Books, 2021) and Unfettered Spirit: Spiritual Gifts for the New Great Awakening, 2nd Edition, (Energion Publications, 2021). His blog Ponderings on a Faith Journey can be found at www.bobcornwall.com.