Book cover detail from “Becoming Human: The Holy Spirit and the Rhetoric of Race”

BECOMING HUMAN: The Holy Spirit and the Rhetoric of Race. By Luke A. Powery. Foreword by Willie James Jennings. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2022. Xvii + 141 pages.

We continue to face questions about race and racism in our society. Even as efforts are made to address long-standing obstacles and even oppression faced by people of color, we’re also seeing strong pushback against anti-racism training and even conversations about the reality of racism in American history (often under the banner of opposition to the little-understood Critical Race Theory). This is not a comfortable conversation to participate in, no matter one’s race or ethnicity. While many in American society embrace a vision they see present in Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, where he speaks of a dream of a day when people would be judged by the content of their character rather than the color of their skin. This has led to an embrace of such slogans as being color blind (I don’t see race) or “All Lives Matter” as opposed to “Black Lives Matter.” Of course, all lives do matter, but in our society, we have to ask whether this is true. The idea that the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s or the election of a Black President solved all our problems might be an enticing belief, but there is plenty of evidence that we have not yet become that envisioned post-racial society. That phrase from King’s speech is enticing, but it is both misinterpreted and pulled from its larger context. Thus, the color of our skin still matters in our society, including in the church.

Robert D. Cornwall

Recently many books have appeared that address these questions, especially within the Christian context. One of those books, one that is beautifully written, is Luke Powery’s Becoming Human. The title and subtitle of Powery’s book remind us that at the end of the day, we are all human beings. The question is, for the church, how do we understand our humanity? While we are mortals who share a common humanity, race still matters. At least the social construct of race continues to matter. Powery brings to the current conversation that is present in both the church and the larger community his expertise as a preacher and teacher of preachers. More specifically he writes as a Black man teaching at a historically white institution that has a rather racist historical legacy. It is that context, his calling to serve as Dean of the Chapel and associate professor of homiletics at Duke University, that provides a larger context to this conversation. The foreword to this brief but powerful book is offered by Powery’s former colleague, Willie James Jennings, who notes that Powery addresses the question of resistance to the Spirit and the racial condition of the Western world. Thus, he writes as a prelude to Powery’s message: “Only from the embodied irony of being a preacher may one feel the thorns of this fundamental contradiction: Christians sometimes resisting the Spirit by refusing to see the full humanity of Black people and sometimes resisting the Spirit by resting comfortable in racial logics that nurture segregation, hierarchy, and white supremacy” (p. x).

Powery writes to preachers about the relationship between race and the Holy Spirit. It is, as Jennings reminds us in the foreword, a word to preachers about the danger of resisting the Spirit in the context of racial disparities. Powery’s focus in this book is his effort to get us, as preachers, to take the Holy Spirit seriously so that we can live into a new humanity in the Spirit such that we can overcome a racialized context. Getting there does not require us to erase our ethnic identities or the color of our skin but to understand them in a new way.

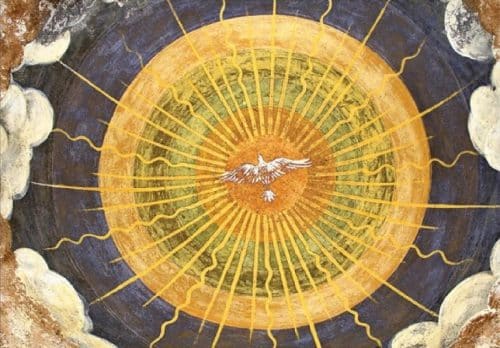

One thing I’ve learned in recent years, being a white male, is the importance of listening to the stories of those who have experienced racialized lives. When it comes to being racialized, Powery suggests that this involves being “erased from the sphere of humanity.” So, to become human involves an act of the Spirit that helps overcome this reality. To understand what it means to become human starts by recognizing that race is not biologically defined, though there were attempts that ran well into the twentieth century that sought to “prove” this to be true. Rather than race being a biologically defined construct, it is a social construct that has the social power to control others. Here is something important to grasp, something often missed or misunderstood—when we speak of whiteness, we’re not talking about a biological thing but a way of organizing life. Powery writes that “racialization perpetuated by whiteness has historically been about the power to control and destroy, racing that which needs to be dominated because it is perceived to be in the way, economically, socially, or even religiously” (p, 5). In dealing with this reality Powery brings the Holy Spirit into the conversation. He believes that it is the Spirit who can blow into our context and push back in the other direction of our racialized reality. The Spirit can, he suggests, “help us reclaim our humanity with all of its rich particularity of culture, language, and ethnicity” (p. 9). He draws on the image of Pentecost, where we find a list of people of diverse ethnic identities all being drawn together by the Spirit as a foundation for the creation of this new humanity.

When it comes to the organization of this rather brief book, Becoming Human is divided into five chapters. The first chapter deals with the reality of a history of inhumanity, and the ways it exists, including homiletically and liturgically. This is a reminder that racialization has been present and continues to be present in the church. This reality was symbolized until recently at Duke Chapel, where he presides, by a statue of Robert E. Lee that stood in front of the chapel door. This statue served as a constant reminder of Duke’s racist origins, symbolized by a key leader of the Confederate defense of slavery. Then in chapter two, titled “Oh Freedom,” Powery deals with the past efforts to root race in biology, which was designed to demonstrate the superiority of the “white race.” In response, he seeks to deconstruct those ideas in a way that redefines race as a social construct. As for the Holy Spirit, the Spirit seeks to “form a community of diverse and beautiful human beings, not for a hierarchy but for unity and equality within the human race.” (p. 50).

Power titles chapter 3 “Every Time I Feel the Spirit.” In this chapter, Powery attempts to create a pneumatology of particularity. This pneumatology reveals that “the inhumanity of antiblackness, anti-Black body, and anti-Black humanity is actually anti-Spirit,” for as Paul reminds us, our bodies are the temple of the Holy Spirit (p. 51). Here is where he roots an affirmation of diversity in the Pentecost story, which he believes, rightfully in my mind, that the wind of the Spirit blowing on the Day of Pentecost “confronts the dehumanization of racialization” (p. 59). That they were in one place does not mean this place was homogenized ethnically or linguistically. The message of Pentecost is the creation of a unified diversity, and this is the creation of a new humanity in the Spirit.

In chapters 4 and 5, Powery builds on these foundations to speak to how preaching and pastoral ministry fits into these conversations. He titles chapter 4 “There’s Room for Many-a-More,” where he speaks about homiletical matters. Here he addresses how race is typically treated in homiletical literature and then moves us toward envisioning a new form of preaching that is rooted in the Spirit and can deal with difference, especially racial difference. As such it moves us to a humanizing homiletic where we can affirm “all humans as beautiful creatures of God.” (p. 83). While reconciliation is still an eschatological hope, our preaching can, quoting HyeRan Kim-Cragg “rehearse reconciliation until it comes, because it is what is truly needed in a racialized world that divides and dehumanizes. This homiletical rehearsal not only speaks of how God makes creation whole by proclaiming a God who ‘reconciles us into a new humanity.'” (p. 103). Then in Chapter 5, titled “There Is a Balm,” Powery addresses pastoral ministry as a whole. Here he focuses on ministering as humans, drawing on Jesus’ humanity as a foundation. Such a ministry will attend to suffering bodies, especially the marginalized ones. He points out that “A ministry with humanity reminds us that human beings are more than a head on a pile of books. To proclaim the gospel in word and deed necessitates a whole human person, spiritual and physical, the spirit and the body, the spirit in the body and the body in the person. Only a whole person can do holy ministry wholly” (p. 111). Ultimately this is a call to becoming a community of diverse humanity that is no longer racialized.

While Becoming Human is not a lengthy book it is a powerful one. While many books have been written on racism and the church, some of which speak to the act of preaching, Powery brings the Holy Spirit into the conversation in such a way that we can re-envision our common humanity. By dealing directly with race he reveals the inhumanity present in our world. He then offers the Spirit of God as the key for us to become truly human. In doing this, we can see that it is possible to embrace our diversity while setting aside the racialization that seeks to divide and diminish the true humanity of all people. He does this through analysis of our historical and current context, including how racialization has come to be. He draws upon theology, especially the theology of the Holy Spirit, to provide a theological foundation for responding to the racialization present in society. Then, working from these foundations he can offer a word of wisdom to those who preach and provide pastoral ministry, such that as we embrace the work of the Spirit in our midst, we will see how the Spirit informs and humanizes our work. For this, we can be thankful, making this a book that should be read closely by clergy whatever our ethnic identity.

This review originally appeared on BobCornwall.com.

Robert D. Cornwall is an ordained minister in the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ). Now retired from his ministry at Central Woodward Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) of Troy, Michigan, he serves as Minister-at-Large in Troy. He holds a Ph.D. in Historical Theology from Fuller Theological Seminary and is the author of numerous books including his latest books: Called to Bless: Finding Hope by Reclaiming Our Spiritual Roots (Cascade Books, 2021) and Unfettered Spirit: Spiritual Gifts for the New Great Awakening, 2nd Edition, (Energion Publications, 2021). His blog Ponderings on a Faith Journey can be found at www.bobcornwall.com.