LONDON (AP) — Three centuries ago, an enslaved person in Virginia wrote to a leader of the Church of England, begging to be released from “this cruel bondage.” There was no reply from the church, which at the time was accumulating a tidy profit from the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

The handwritten letter from 1723 — whose author says they must remain anonymous for fear they will “swing upon the gallows tree” if exposed — has gone on display in London as part of efforts by the Anglican church to reckon with its historic complicity in slavery.

“It’s a very poignant document, and also extraordinarily rare,” Giles Mandelbrote, archivist at the church’s Lambeth Palace Library, said Tuesday (Jan. 31).

The letter is included in an exhibition at the library exploring the church’s role in the 18th-cenury slave trade. It coincides with a new report setting out that role in hard facts and figures. The Church Commissioners, the body that administers the church’s 10 billion-pound ($12.3 billion) investment fund, hired forensic accountants in 2019 to dig through the church’s archives for evidence of slave trade links. They spent two years poring over centuries-old ledgers, and what they found is “shaming,” the church said.

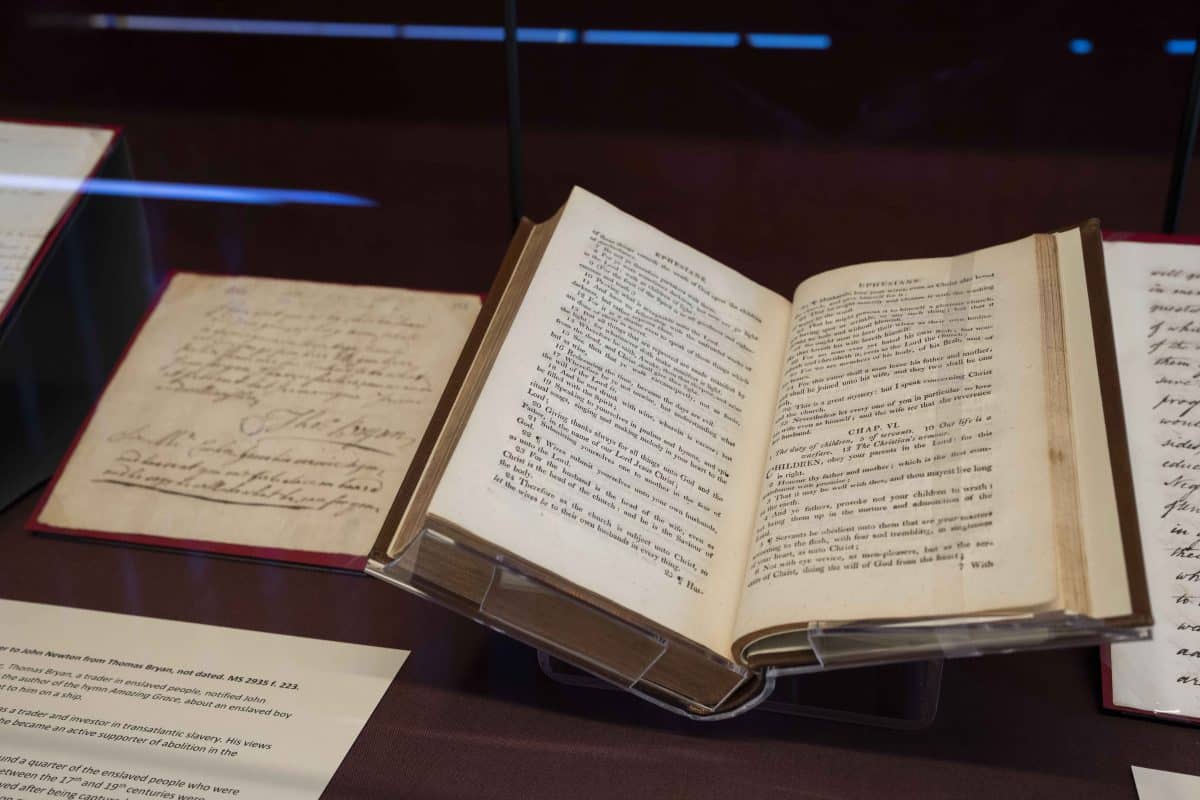

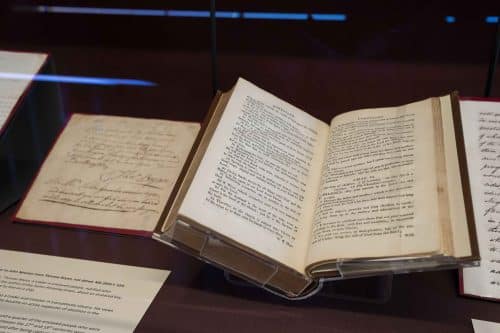

A “slave bible” published in 1808, with all references to freedom from slavery removed, is displayed at the exhibition in the Lambeth Palace Library, in London, on Jan. 31, 2023. (Kin Cheung/Associated Press)

The investment fund has its roots in Queen Anne’s Bounty, established in 1704 to help support impoverished clergy. It invested heavily in the South Sea Company, which held a monopoly on transporting enslaved people from Africa to Spanish-controlled ports in the Americas. Between 1714 and 1739, the company transported 34,000 people on at least 96 voyages. The commissioners’ report says the church at the time knew what it was involved in.

“Investors in the South Sea Company would have known that it was trading in enslaved people,” it said.

The fund also received donations from individuals enriched by the slave trade, including Edward Colston, a British slave trader whose statue in his home city of Bristol was toppled by anti-racism protesters in 2020. Those ledgers recording the profits of human bondage are now on display, alongside documents showing how views of slavery within the church ranged from justification to opposition.

Some Anglicans wanted to convert slaves to Christianity, while others saw that as a “slippery slope” that could lead to demands for freedom. The exhibition contains a version of the Bible intended for slaves, with all references to freedom from bondage removed. That meant cutting 90% of the Old Testament and half the New Testament.

The exhibition includes tracts justifying slavery in religious terms, and others using faith to argue for abolition, including a 1680 book by Anglican clergyman Morgan Godwyn, who argued that those endorsing the slave trade were making a deal with the devil.

There is a speech to Parliament from 1789 by leading abolitionist William Wilberforce, who would campaign for 18 more years before Britain outlawed the slave trade. And there is a letter to John Newton, the captain of a slave ship, from a trader who says “I have sent you one boy slave on board.” Newton later repented, became an abolitionist and wrote the hymn “Amazing Grace.”

“In the late 18th century, increasingly there was more and more publicity about the horrors of the slave trade and the inhumanity of it, and that helped to generate a movement for abolition,” Mandelbrote said.

Britain outlawed the slave trade in 1807, but did not legislate to emancipate slaves in its territories until 1833.

When the commissioners’ report was published Jan. 10, Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby promised to “take action to address our shameful past.” That action includes a 100 million pound ($123 million) fund to support projects “focused on improving opportunities for communities adversely impacted by historic slavery.”

The commitment falls short of demands from some campaigners for institutions that benefitted from slavery to pay compensation to descendants of the enslaved.

“This isn’t about paying compensation to individuals, and its not really just about the money,” said Church Commissioners chief executive Gareth Mostyn. He said the new fund is part of the church’s “journey of repentance.”

“No amount of money will ever be enough to repair the damage done through the trans-Atlantic slave trade,” he said. “But we hope that our response will be a means of investing in a better future for all.”

“Enslavement: Voices from the Archives” runs until March 31. Admission is free.