Last year, a U.S. Supreme Court ruling mandated that states allow spiritual advisors into execution chambers to touch and pray for those about to be killed. Over the past four months, at least seven people in three states have had a spiritual advisor present during their execution. That included two Christian pastors in Missouri over the past 10 weeks.

But then on Tuesday (Feb. 7), Missouri executed Leonard “Raheem” Taylor after refusing to allow his Muslim spiritual advisor to be by his side.

Taylor’s case raised lots of concerns. He was convicted of murdering his girlfriend Angela Rowe and her three children in 2004. Like the previous two people executed and one-quarter of those currently eligible for execution in Missouri, he was sentenced under former St. Louis County Prosecutor Bob McCulloch, who has a well-documented history of racial bias.

Additionally, there is compelling evidence that Taylor was over 1,800 miles away in Ontario, California, at the time the murders occurred. Numerous people claim to have seen or spoken with the victims after Taylor left the state, and the key witness for the prosecution said he was harassed by police and recanted his statements well before the 2008 trial began. The other pillar of the state’s case was testimony from a medical examiner who actually changed the time-of-death estimate to align with the prosecutor’s timeline of events.

Yet, Taylor was killed before his claim of innocence could be thoroughly vetted.

As if that weren’t bad enough, he was also killed without his spiritual advisor, Anthony Shahid, who is affiliated with the Masjid Al-Tauheed mosque in St. Louis. The Missouri Department of Corrections (MDOC) denied Taylor’s request for Shahid to be in the execution chamber.

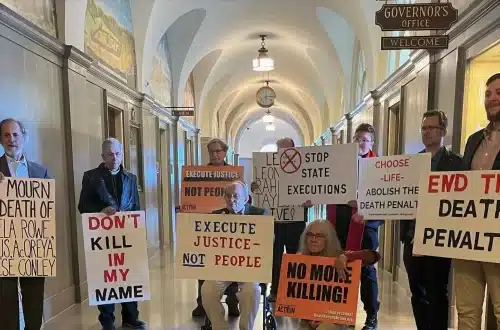

A vigil by Missourians to Abolish the Death Penalty outside of Gov. Mike Parson’s office in the state Capitol in Jefferson City, Missouri, on Feb. 7, 2023, a few hours before Raheem Taylor’s execution. (MADP)

We asked both MDOC and Gov. Mike Parson’s office about the denial and if they were concerned it appeared like religious discrimination to deny a Muslim spiritual advisor after allowing Christian ministers.

“Leonard Taylor was NEVER denied a spiritual advisor. He chose early in the process NOT to have one. DOC’s policy requires individuals to request all witnesses and a spiritual advisor two weeks prior to the execution date,” Parson’s spokeswoman Kelli Jones insisted in an email. “Twenty-four hours before Leonard Taylor’s execution date, he decided to request a spiritual advisor and additional witnesses.”

When we requested the MDOC policy, Jones referred us to MDOC, who we had already contacted. Karen Pojmann, MDOC communications director, initially told us Taylor “signed a document” on Jan. 25 declining “witnesses and/or a spiritual advisor present at the execution.” She added, “It wasn’t until the day before the scheduled execution that he asked to have his spiritual advisor present. He was informed that it was too late to make that change.”

When we again requested the policy, Pojmann responded, “It’s a procedure, rather than a policy.”

So it appears that MDOC never made a policy containing a deadline regarding spiritual advisors in the execution chamber after last year’s Supreme Court ruling — even as the state allowed spiritual advisors to be present. The only policy and document they can point to concerns possible witnesses, like friends and family of the incarcerated person, who can be present outside the death chamber in a separate room at the time of the execution.

Additionally, the statements from MDOC and the governor’s office don’t align with what state officials said in official court filings earlier this week. Both Taylor’s attorneys and Missouri Assistant Attorney General Andrew Crane acknowledged in filings a request for Taylor’s spiritual advisor to be present in the chamber was made on Saturday, Feb. 4 — two days before the timeline MDOC said publicly and more than three times longer than the 24-hour claim by the governor’s office.

Taylor’s attorneys filed suits in state and federal courts to stop the execution unless Shahid was allowed into the execution chamber. They argued that Taylor was told the form he signed two weeks earlier was about family members as witnesses, which he didn’t want. Additionally, the suits noted that the form he signed did not include an option to designate a spiritual advisor for inside the chamber. Instead, the form follows a Missouri statute allowing the condemned person to have two “ministerial counselors” in the adjacent witness room along with up to five other witnesses. Neither the statute or the form addresses having a spiritual advisor in the actual execution chamber, which presumably would not be an option for two ministerial counselors.

“Given the right to have a spiritual advisor in the execution chamber, [the MDOC is] required to provide a process that satisfies due process,” Taylor’s suit read. “The MDOC’s unstated, unclear, and arbitrary policy, which resulted in the refusal to admit his spiritual advisor of the Muslim faith, but permitted the two Christian spiritual advisors to be present for the executions of Amber McLaughlin and Kevin Johnson, violates Mr. Taylor’s First Amendment rights under the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act.”

Although the state of Missouri defended its denial of Taylor’s request in court filings, their attached exhibits show there is not actually a policy or set procedure for requesting a spiritual advisor to be in the room. In fact, the filing includes emails from attorneys for the previous two individuals executed showing them trying to figure out how to get a spiritual advisor in the chamber. In both cases, that was not considered covered by the witness form but was a request for “an accommodation.” As Greg Godwin, chief council for the Missouri attorney general’s office, noted in an October email, “The Warden considers these requests on a case‐by‐case basis.” Taylor’s Feb. 4 request for his spiritual advisor to be present was also called an “accommodation” request, but it was denied.

Additionally, while public statements said Taylor had to make the request two weeks in advance, the state told the courts they required seven days’ notice, insisting they needed to clear people for security reasons — even though Shahid had already been approved as a spiritual advisor for Taylor and cleared to meet with him in prison.

The Missouri Supreme Court on Tuesday rejected without an explanation Taylor’s suit regarding his spiritual advisor. These same justices were criticized by Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson in a dissent in Kevin Johnson’s case from November for not properly following Missouri law when they allowed Johnson’s execution to proceed. But Jackson and her fellow members of the nation’s highest court never got a chance to consider Taylor’s suit about his spiritual advisor. Although his attorneys filed an appeal with the Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit (one step before the U.S. Supreme Court would have seen it), they never got to consider the case because Taylor was killed before they could do so.

The gurney in the execution chamber at the Oklahoma State Penitentiary in McAlester, Oklahoma, on Oct. 9, 2014. (Sue Ogrocki/Associated Press)

Was this a case of Islamophobia since the two previous Missouri executions allowed Christian ministers to be present? Was this a case where the state did not like that these spiritual advisors were speaking publicly about their experiences, such as Rev. Lauren Bennett noting that Amber McLaughlin died in pain last month? Was this a case where Taylor was confused by an unclear, arbitrary process and then was himself blamed for the confusion by those leading that process? Or was it a bit of all of the above?

Now that we’ve detailed what went wrong, this issue of A Public Witness will explore the U.S. Supreme Court’s recent record of requiring states to allow spiritual advisors in the death chamber and the advocates who were pushing Missouri’s leaders to do better on Tuesday.

The rest of this piece is only available to paid subscribers of the Word&Way e-newsletter A Public Witness. Subscribe today to read this essay and all previous issues, and receive future ones in your inbox.