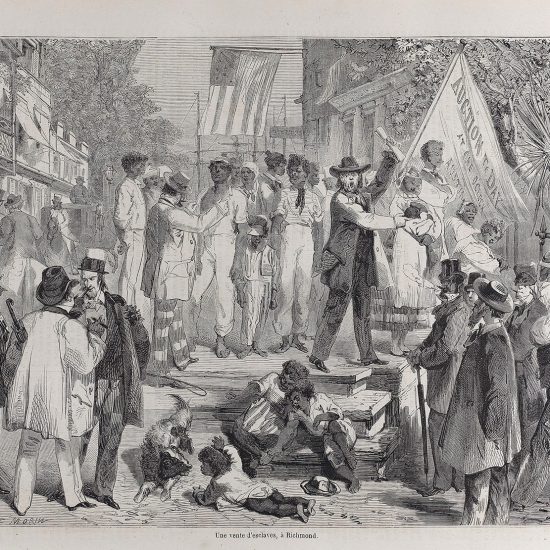

On the campus of Samford University in Birmingham, Alabama, there are two memorial markers to Harry. That’s the only name he’s given since he was an enslaved person. Harry is honored because in 1854 he died while saving students from a fire on campus.

Why was Harry there? Because he was enslaved by the president of this Baptist school.

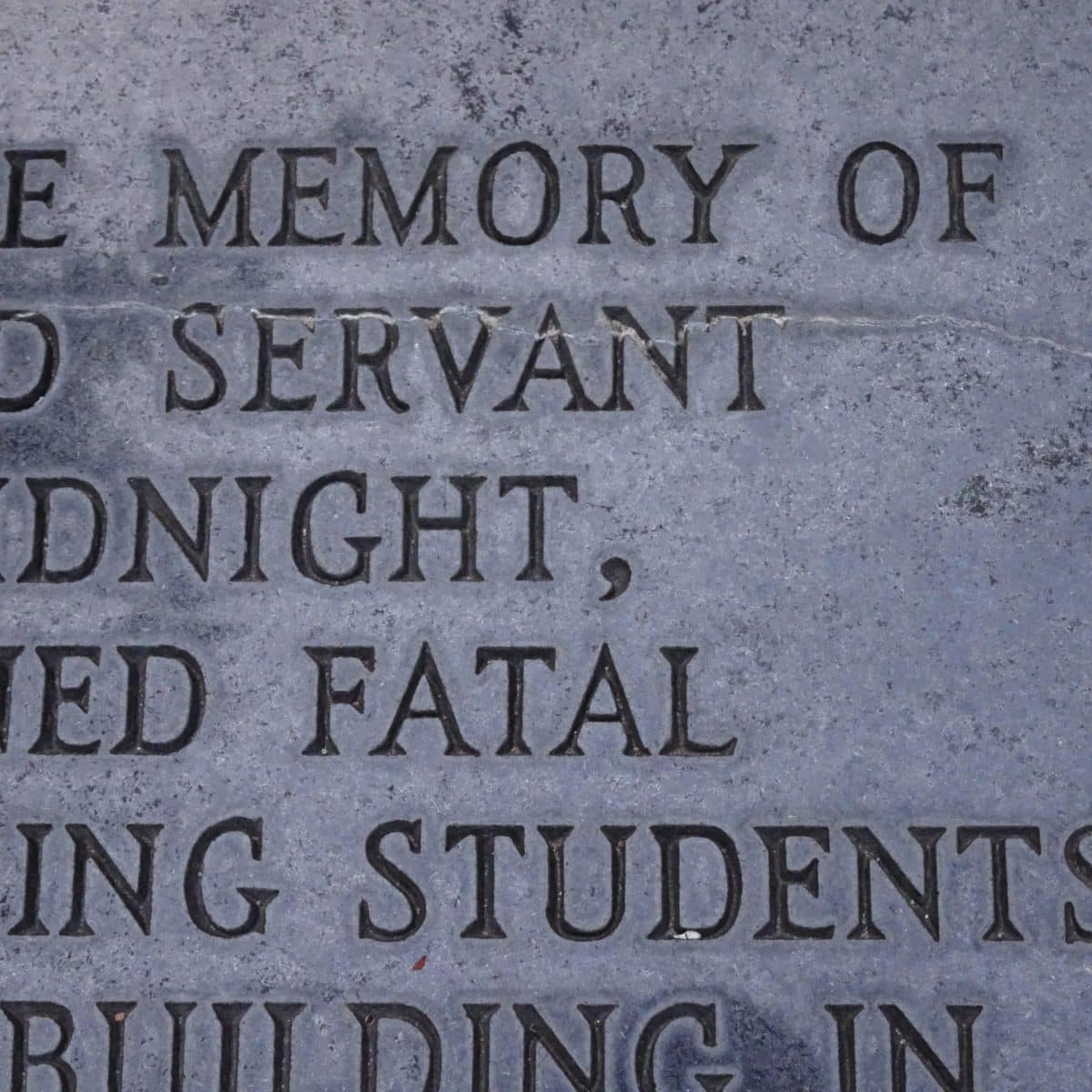

An earlier memorial referring to Harry as a “servant.” (Brian Kaylor/Word&Way)

The school has evolved in the way it honors Harry, which helps us all think about how we should deal with the past and remember it today.

An older marker on campus referred to Harry as “college janitor and servant of President Talbird.” The word “servant” hardly conjures up the right picture. And in an interesting unintentional metaphor, a crack that’s emerged in the stone cuts through the top of the word “servant.”

In light of racial justice protests during 2020, the school installed a new marker to honor Harry and the first African American student admitted to Samford. The new marker acknowledges slavery, though it leaves out who enslaved Harry as it calls him “an African American man who lived in slavery.”

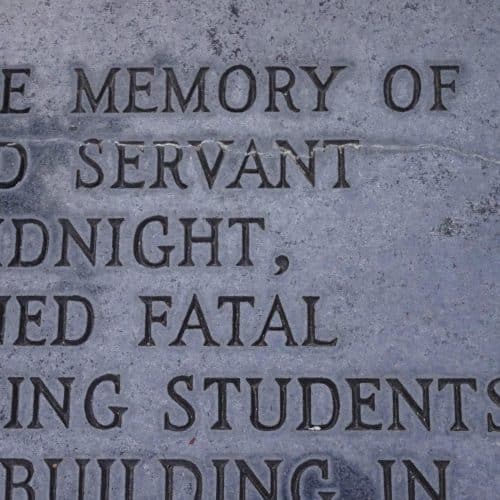

A obelisk installed in 2020 that honors Harry and other African Americans

at Samford. (Brian Kaylor/Word&Way)

Harry was hardly alone at Samford. President Henry Talbird, who left the school to fight in the Confederate Army, enslaved 10 persons in 1860 while serving as president. The first and third presidents also enslaved people, as did each of the four people honored as the key founders of the school — which gives a hint to how they were so wealthy to be able to fund the launch of a new college. Samford honors those

individuals with monuments on campus and in statements online, but leaves out the ties to slavery.

This isn’t to pick on Samford. The school is doing a lot of things well in an environment when many Christian schools are struggling to keep their campuses open.

And numerous Baptist and other Christian colleges, churches, and other institutions have a similar history with slavery and a similar record today of barely (if at all) acknowledging that past. Stories like a former president (or pastor) enslaving other people aren’t the type we usually highlight in our histories or tout in our anniversary celebrations.

That’s why when I visited Samford’s campus last year for a meeting of the Baptist World Alliance, global Baptists from around the world passed a resolution on slavery reparations that urged Christians to learn and reckon with their own history. The resolution, which came from the committee that I chair, called on “older Baptist churches, colleges, unions, and other institutions to thoroughly study their own history and publicly acknowledge institutional and leadership ties to chattel slavery, and then explore ways to repair the damage from previous support for and profiting from slavery.”

It matters when we tell the truth — or not — about our institutions. It matters that we acknowledge the truth clearly, avoiding euphemisms like “servant” or leaving out the duplicity of our former leaders. And it matters if take steps to lament institutional sins and work to repair the damage today.

“Healing requires repentance. Repentance requires truth-telling,” Lisa Sharon Harper, author of Fortune: How Race Broke My Family and the World — and How to Repair It All, told me. “Institutions like Samford are standing at a crossroads. Their choice has the power to bless or curse our nation and the church.”

May we be truth-tellers. May we be a blessing.

Brian Kaylor is editor-in-chief & president of Word&Way.