WINSTON-SALEM, N.C. (RNS) — Each Wednesday evening, a group of congregants from First Baptist Church of Mt. Olive, located about 65 miles southeast of Raleigh, gathers for a Bible study called “Tackling Tough Topics Together.” The 10 to 20 regulars have discussed race, human sexuality and mental illness.

Those kinds of conversations are rare and becoming rarer at churches like First Baptist, which is affiliated with the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship, a network of congregations that offers a moderate alternative to the Southern Baptist Convention.

CBF-affiliating churches generally allow for women’s ordination and view the Bible as authoritative but not literal. They are distinguished these days by the diversity of their congregations, mostly white, but tending to be split nearly equally between Republican-leaning and Democratic-leaning voters.

They are, as the CBF of North Carolina likes to call themselves, neither red nor blue churches, but “purple.”

In an era of increasing polarization, when a deeply acrimonious partisan divide has permeated nearly all aspects of American life, including church, that’s a tough spot to be in.

A recent survey of 467 local pastors by two University of North Carolina political scientists found that of seven Christian groups surveyed in the state, Cooperative Baptist churches were the most evenly politically divided, ahead of Methodists, while, at the other end, Pentecostals and Southern Baptists were least divided.

That makes political discussions in the country’s 1,800 or so CBF-affiliating churches particularly fraught, because pastors risk alienating half the church’s members.

“It’s constraining the kind of debates on moral issues that pastors in purple churches feel comfortable addressing,” said Liesbet Hooghe, a professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who authored the study along with Gary Marks and Stephanie N. Shady.

For First Baptist’s pastor, Dennis Atwood who attended the leadership forum for CBF pastors in Winston-Salem last week, the effort to reach members about the moral issues of the day is worth the effort.

“We’re pushed into dualistic thinking where we have to have either/or,” he said. “My approach is to model a big tent approach. We can have unity without uniformity.”

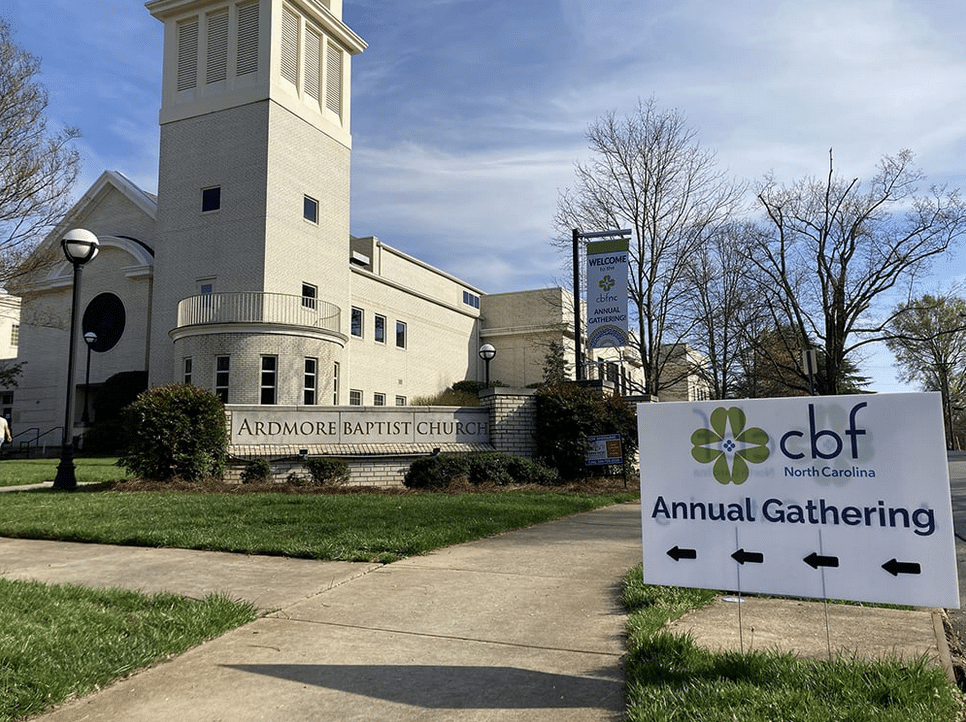

Ardmore Baptist Church in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, was the site of the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship of North Carolina’s Annual Gathering on March 23-24, 2023. RNS photo by Yonat Shimron

Historian Kristin Kobes Du Mez, whose bestselling book “Jesus and John Wayne” traces the rise of militant masculinity in evangelical churches, spoke at the retreat about the difficulty of leading an evangelical congregation in polarizing times.

“Most white evangelicals were not marching with neo-Nazis in Charlottesville, nor were most evangelicals storming the Capitol on Jan. 6,” Du Mez told some 200 church leaders at the leadership forum, sponsored by CBF of North Carolina, on March 23. “But it’s also true that underlying affinities make it difficult for mainstream moderate evangelicals to unequivocally condemn these acts.”

The coronavirus pandemic exacerbated polarization as masking and meeting in person became flashpoints among members. Several CBF pastors said they lost members who either thought the church was too cautious to reopen or not cautious enough.

Many CBF pastors at the leadership forum said they struggle with preaching about political issues. Some said their solution is to stick as closely as possible to the biblical texts and rely on the lectionary, or appointed Scripture readings, to guide what they say on Sunday mornings — only speaking to political or cultural issues if there’s a direct analogy in the text.

That strategy has helped Lee Canipe, pastor of Providence Baptist Church in Charlotte, which affiliates with the CBF. Church members can criticize his interpretation of a Scripture passage, but, he said, will not offer opinion.

“People tend to be much more open to hearing something uncomfortable when it’s coming from the Bible,” Canipe said.

Last week’s forum offered these often-besieged pastors workshops with titles such as “Self Care in an Anxious Age,” and “Effective Leadership in a Time of Polarization.”

At one workshop, writer, theologian, and former pastor F. Timothy Moore challenged pastors to think of the Bible as a text that lends itself to numerous interpretations. He pointed out that the Bible has multiple accounts of key stories, including the creation story, the Ten Commandments, and Jesus’ birth.

Most pastors conflate the different versions of these stories or try to smooth out the contradictions.

“In a polarized world, what would happen if we considered teaching the Bible as a conversation or a dialogue with multiple ideas?” Moore asked a group of pastors.

Balancing those interpretations and mustering the courage to speak out on moral issues of the day is no easy task. Yet, as Du Mez told the church leaders at the conference, the stakes are high.

“The state of democracy and possibly our communal good may come down to the folks in the middle,” she said. “If you feel like you’re up against a lot, you are.”