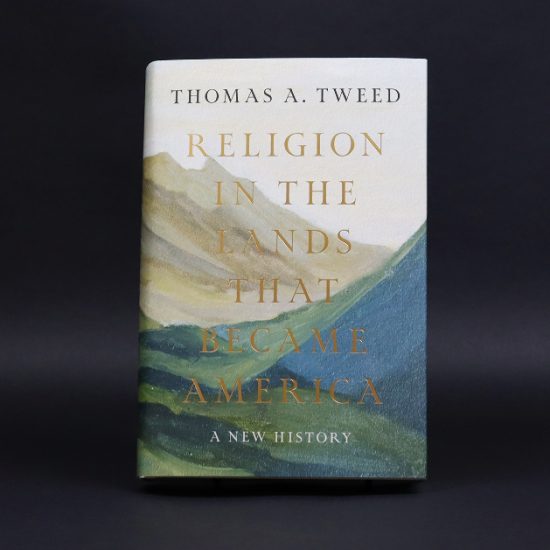

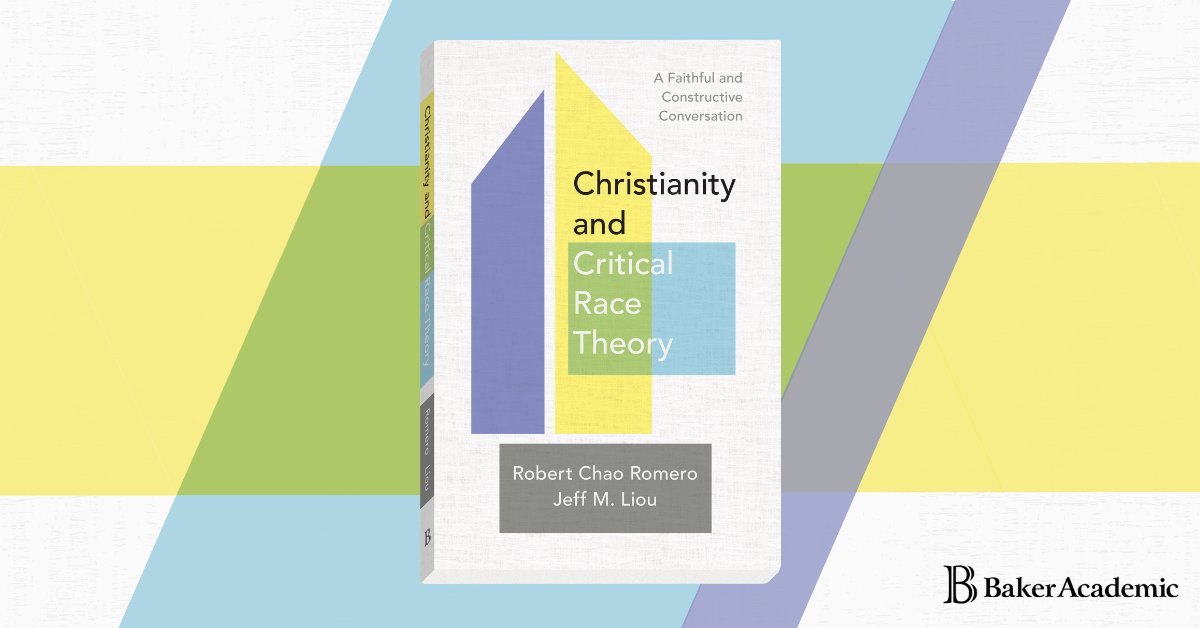

CHRISTIANITY AND CRITICAL RACE THEORY: A Faithful and Constructive Conversation. By Robert Chao Romero and Jeff M. Liou. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2023. Xi + 196 pages.

Back in the third century C.E., Tertullian asked “What has Jerusalem to do with Athens?” In many quarters today, something similar to Tertullian’s question is being asked. This time the question has to do with what Christianity has to do with Critical Race Theory (CRT). In the minds of many, or so it seems, Christianity and Critical Race Theory are completely antithetical. In fact, for many, CRT along with “Wokeness” is perceived to be a threat to Christianity. The problem is that CRT and Wokeness serve as catchall terms for theories and actions that make certain people, mostly white and Christian (largely evangelical), uncomfortable. The problem is that when people are asked to define CRT (and Wokeness) they find it difficult to answer with any specificity. They don’t quite know what it is, but they’ve been told that it is bad. Why is it bad? Well, supposedly, it’s Marxist — but what if CRT offers important truths (not alternative truths or facts but truth itself)? But, as the early church came to understand Athens did have something to offer Jerusalem, and if understood properly, CRT could also have something positive to offer Christianity. But, if we are going to discern what that CRT might contribute to Christianity requires a deeper dive into the arena with CRT.

What we need, first of all, are guides who understand CRT and are Christian. Fortunately, we have the appropriate guides in Robert Chao Romero and Jeff Liou. Both Romero and Liou are, by confession, evangelicals who have discovered that CRT has something important to offer Christianity. However, they also believe that for CRT to be helpful it needs to be augmented by additional resources. When CRT is brought into the conversation it can help the church address the reality of racism in the nation and the church. They make it clear that racism is still a problem for the church and that the appeal to color blindness is not a solution. This reality makes Christianity and Critical Race Theory a must-read book because this issue of racism in church and society isn’t going away. In fact, the divide seems to be getting wider and that is to the detriment of the church writ large.

Both authors bring academic and evangelical credentials to the table. Robert Chao Romero is a professor at UCLA, who teaches in the departments of Chicana/o, Central American, and Asian American Studies. He also holds an M.Div. degree from Fuller Theological Seminary. He is also the author of the excellent book Brown Church: Five Centuries of Latina/o Social Justice, Theology, and Identity, (IVP Academic, 2020). Romero has Mexican ancestry on one side of the family and Chinese on the other. He has faced significant discrimination in the course of his life. His coauthor is Jeff M. Liou, who is of Taiwanese ancestry, holds a Ph.D. from Fuller Theological Seminary and serves as the national director of theological formation for Intervarsity Christian Fellowship/USA. Both of the authors are involved in the life of Fuller Seminary (my alma mater). In other words, these are not far-left anti-Christian enemies of the church. They are deeply engaged in the life of the church and believe that justice and Christian spirituality go together. It is from this foundation that the two authors find value in CRT for the church and the world.

The two authors begin their book by introducing themselves to the reader. Therefore, we know up front where they’re coming from. We know that they speak from personal experience, as well as academic study, that systemic racism still plagues our society. They know from personal experience that the racialized experiences they describe in the book are not isolated but are “part of larger structures and systems that have been supported by centuries of law, policy, and even theology” (p. 5). It is this revelation that racism is structural and systemic that makes many uncomfortable. So, it’s easier to reject the tool that reveals this reality than to deal with the revelation. That’s what makes CRT dangerous in the eyes of many — it provides a lens by which these realities can be examined and ultimately dealt with.

While the acronym CRT is bandied about in political and church circles, few seem to know what it is in reality. So, what is CRT? Romero, who uses CRT in his work, helpfully defines it as a lens through which scholars examine the “intersection of race, racism, and US law and policy.” He writes that CRT “looks at how US laws and public policy have been manipulated and constructed over the years to preserve privilege for those considered ‘white’ at the expense of those who are people of color” (p. 7). This theory first emerged among legal scholars, led by Derrick Bell (who once served as the dean of the University of Oregon Law School). While CRT provides a useful lens to examine the legal and cultural dimensions of racism, the authors also note that it lacks a “hopeful eschatological vision of the believed community of all.” In this book, they want to bring the two together so that the analysis can lead to a change of hearts and society. In other words, Romero and Liou believe that Jerusalem has something to offer Athens, even as Athens can speak to Jerusalem.

When it comes to defining the basic tenets of CRT, the authors make it clear that according to this theory that “racism is ordinary” and not an aberration. It’s simply part of the normal way things are done in our society. Secondly, CRT lifts up “interest convergence or material determinism.” That is, racism gives advantages to both white elites (materially) and working-class whites (psychically). As a result, a large part of society has little interest in eradicating racism. Third, it offers a social construction thesis, such that race is a social construct, not a biological/genetic reality. Fourth, CRT offers a “voice of color thesis.” This thesis suggests that people of color, due to their own experiences with racism and oppression, are the ones best equipped to speak realities whites might not be in a position to understand. In other words, as a White European-American I don’t know and can’t know what it means to be Black or Latinx or Asian unless I listen to the voices of people of color, and even then, it will be an imperfect understanding. Other elements of CRT include intersectionality, white privilege, etc.

Why is this theory important to the church? As Romero notes, a large number of persons of color are being forced to choose between their God-given cultural treasure and White Christianity. Romero shares his concerns about the challenges facing what he calls the Brown Church in his previous book, concerns that are rooted in his encounters with students who find the church unfriendly to their concerns. Here it might be worth noting the challenge of assimilation, which often restricts the gifts people of color bring to the church and the nation as a whole. In other words, one need not become European American to be Christian. Or, as they point out, God might not have ethnic favorites, but neither is God color-blind.

Romero and Liou offer this book to the church because they believe that “a faithful and constructive engagement with CRT illuminates significant overlaps with Christian theology” (p. 21). With that in mind, they invite us to join them in exploring the connections between the two by using a classic biblical narrative schema that begins with creation and continues by drawing on the themes of fall, redemption, and consummation. Thus, in chapter one they explore CRT in light of a doctrine of creation. In this chapter, they speak of what they call the “community cultural wealth and glory and honor of the nations.” With this in mind, they lift up the premise that every culture and nation has cultural wealth that needs to be honored. In other words, European culture is not less than but is also not superior to other cultures. In other words, Latino, Asian, and African cultures are deficient in comparison to European culture. They address the problem of the efforts to erase cultures through “assimilation.” CRT helps us see the cultural wealth present among people of color. It’s important to understand that when we hear about education focusing on Western Civilization, those proposing it envision the superiority of European culture at the expense of other cultures, which they see as being deficient. In exploring this concept, they reveal the realities of racism in the United States, which continues to this day. In response, they conclude by asking us to reimagine churches and ministries so that the cultural wealth of diverse communities can be integrated (not assimilated) into the larger body of Christ.

In chapter two, which they title “Fall,” they deal with the sin of racism. Jeff, who is Taiwanese, opens the chapter by taking note of the anti-Asian racism that emerged as the COVID-19 pandemic materialized in 2020. In this chapter, the authors again turn to the presupposition that racism is ordinary and not an aberration. It is personal but it’s also systemic. CRT is useful in discerning the presence of systemic racism. That is why it makes many White folks uncomfortable. We want to believe that we’re not racist. If we’re not racist, how can the country be racist? Yet, this is the way things are. Even as we know, theologically, that sin is defined as both personal and systemic, racism is both personal and systemic. Whether we embrace a full-on Augustinian perspective on original sin, we know it’s there and that it forms us as individuals and as a society. However, as we move on in the book, there is good news. They note that “the very existence and persistence of communities of faith that have endured the ravages and innovations of racism bear witness to the love of God in Christ” (p. 98).

The message of hope previewed at the end of chapter two is developed further in chapter three. They remind us that while the structures of society (including the church) may be infected with racism, there is hope for redemption. They suggest that we see this hope of redemption revealed in the browning of the church as well as the browning of the nation. Again, this browning of America and the church may make some uncomfortable, as we hear regularly, especially by those who speak in terms of the “Great Replacement” theory. While some are uncomfortable with these realities, the browning of the church and nation has redemptive qualities. This is where the “voices of color” thesis comes into play. According to this thesis, people of color are in the best position to understand their racialized experiences as well as craft solutions. The authors want to make sure that their readers understand that these “perspectives are not better than others, yet flowing from our experiences as unique children of God, they are distinct” (p. 109). In other words, we’re all distinct members of the body of Christ who need each other.

It is in this chapter that they deal with what they call “reactionary colorblindness,” wherein the majority culture says they don’t see the color of a person’s skin, and yet they show no interest in the perspectives and gifts that people of color bring to the table, including in the church. The expectation among the majority culture is that people of color essentially become white so they can fit into the already dominant cultural dynamics (assimilation). This idea of color blindness ultimately leads to perpetuating racialized structures of inequality. I believe that this section dealing with colorblindness is especially relevant and important if we’re going to address what ails us as a society (find redemption). There is one more stage in this movement of redemption that we must engage with. This is where eschatology comes into play. The authors point to the celebration of diversity found in the Book of Revelation, where the nations gather before the throne of God. That is the theme they pick up in chapter four.

Chapter four is titled “Consummation: Beloved Community.” In this chapter Romero and Liou speak of the beloved community, which they suggest is the eschatological goal toward which CRT points but doesn’t fully express. It’s important to note that when we’re speaking of eschatology here, it is an inaugurated form. That new reality, the realm of God, does not wait for a new world to emerge, but it begins in the present. It is a reflection of the already/not yet vision we find revealed in Scripture. [If I might take a point of privilege here, I would offer as an additional resource for the conversation about eschatology, the book Ron Allen and I co-authored—Second Thoughts About the Second Coming, (Westminster John Knox Press, 2023). We wrote this book because we have found that in mainline circles there is a lot of avoidance of discussions of eschatology. Thus, our book might serve as a primer for the discussion here in Christianity and Critical Race Theory]. In this chapter, Romero and Liou write that “in the cross and resurrection, the power of God has already broken into the world, and Christians enjoy the hopeful promise of resurrection power in this life” (p. 139). With that premise, where might CRT fit? According to the authors, CRT fits in because it gives us tools to discern the obstacles to living into that resurrection vision so that we might begin to dismantle them. What a Christian eschatological vision does for CRT is move it beyond the gloomy outlook of the future. Yes, there are many obstacles out there that must be torn down, but change can happen. In other words, what is” does not have to be the way “it always is.”

In their exploration of CRT and Christianity, they believe eschatology provides CRT with a specific ethical vision of the desired community which God is creating in our midst. This ethical vision includes the legal and legislative efforts that we must engage in, but it pushes further beyond these realities to embody God’s realm in the form of the Beloved Community. As for the benefits accrued to the Christian community, the benefits of this movement into the Beloved Community not only blesses the Christian community, but it enables the church to fulfill its calling to be a blessing to the nations. What holds us back, in their estimation is the presence of a “thin eschatology” that “conveniently forget the disruptive coming reign and rule f God in Christ. We may say that God’s justice is otherworldly and that God’s ways are higher than ours, but we live placidly, as though there is little left to be done in the world, choosing instead to focus on private spiritual delights” (p. 164). However, such is not in keeping with the purposes of God. Thus, we need tools that can reveal the barriers to experiencing God’s justice and rule.

With so much disinformation about CRT and Wokeness, mostly on the part of White Christians, this is a book whose time has come. It is a gift to the church and to our larger culture because it offers an important tonic to the increasingly polarized nature of both church and society. Not only do the authors explain CRT in ways that reveal that it’s not a threat to the church or the Christian faith, but they demonstrate how this theory, which is clearly secular and may have Marxist elements, also aligns with a Christian vision of God’s purposes for our world. If, as the authors note, and which I believe many of those reading this review will concur with, all truth is God’s truth, then if there is truth present in Critical Race Theory, it must be a gift of God to the church and world. Again, I must say that this book authored by Robert Chao Romero and Jeff Liou, Christianity and Critical Race Theory: A Faithful and Constructive Conversation, is essential reading for the church now and in the coming years. For those struggling with definitions, the authors have created a helpful glossary that briefly defines all the relevant terms. Thus, this book should serve as the foundation for a much-needed conversation that must take place if we wish to understand and address the ordinariness of racism that is present in our world so we might participate with God in bringing to fruition God’s purposes for our world.

This review originally appeared on BobCornwall.com.

Robert D. Cornwall is an ordained minister in the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ). Now retired from his ministry at Central Woodward Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) of Troy, Michigan, he serves as Minister-at-Large in Troy. He holds a Ph.D. in Historical Theology from Fuller Theological Seminary and is the author of numerous books including his latest “Second Thoughts about the Second Coming: Understanding the End Times, Our Future, and Christian Hope” coauthored with Ronald J. Allen. His blog Ponderings on a Faith Journey can be found at www.bobcornwall.com.