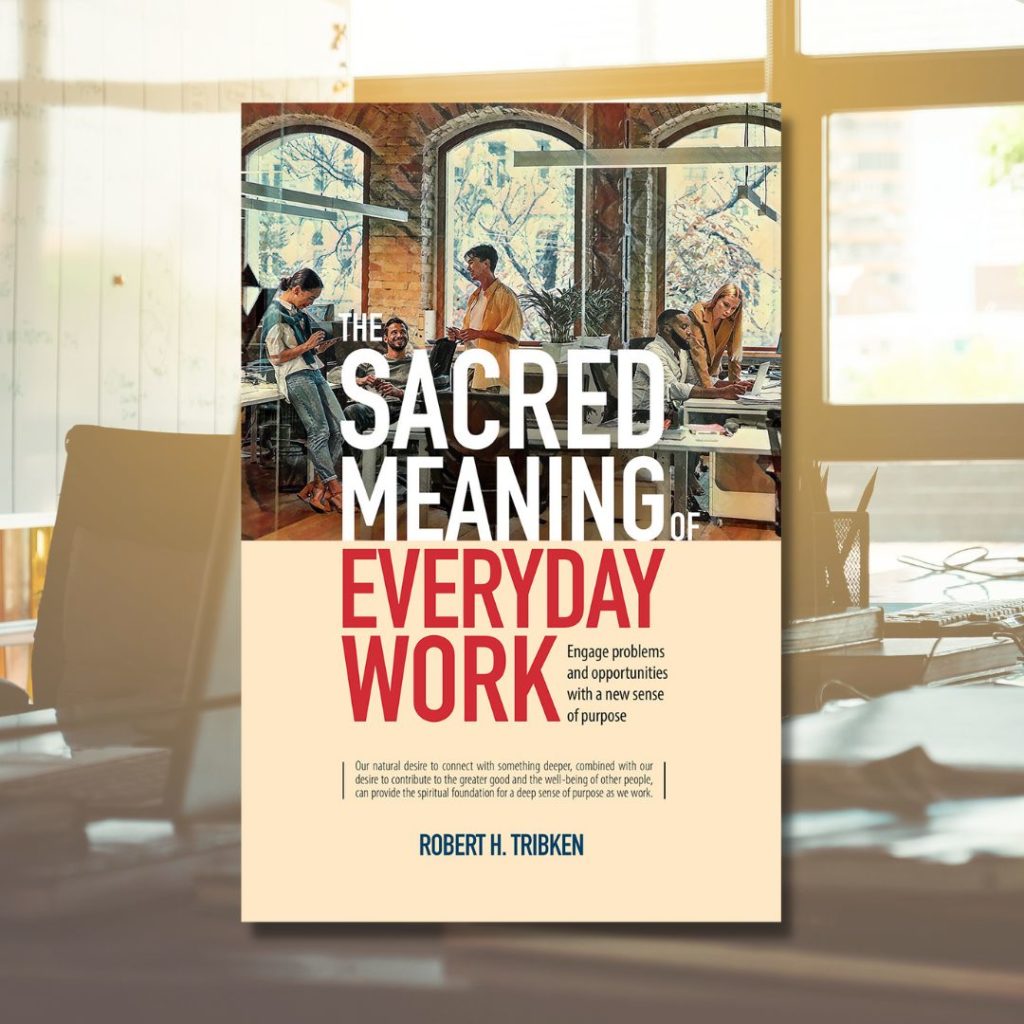

THE SACRED MEANING OF EVERYDAY WORK: Engage Problems and Opportunities with a New Sense of Purpose. By Robert Tribken. Sierra Madre, CA: Faith and Enterprise Press, 2023. 259 pages.

When we hear talk of calling or vocation in the church, our thoughts may quickly go to some form of church work (ministry). As an ordained minister, I have spoken of my calling as a pastor or as a teacher. There’s nothing wrong with that, but what about “everyday work”? Might that be a calling as well? The truth is, we rarely talk about work/labor in the church (that’s true even on Labor Day Weekend). We might talk about justice for the unemployed or those who need to be protected against exploitation, but what about the folks in the pews who go to work every day? What do we have to offer them that can connect their faith with what they do in their jobs?

Robert D. Cornwall

The Sacred Meaning of Every Day Work seeks to answer the question of how faith and work might relate to each other. I will admit that when I was asked to review this book by Robert Tribken, I was a bit skeptical as to what I would find. The very name of the entity with which the author is affiliated — Center for Faith and Enterprise — gave me some pause. The word “enterprise” demands definition. We are apparently moving into the age of the entrepreneur (even pastors are now entrepreneurs). Nevertheless, I ended up finding the book helpful and worthy of consideration. The question raised here has to do with the meaning of work, recognizing that not all forms of work/labor are life-affirming.

So, who is Robert Tribken and why should we consider his views on faith and work? According to his bio, Tribken is a businessman of many decades and the founder of several enterprises. He holds an M.B.A. from Harvard Business School, an M.A. in Theology from Fuller Theological Seminary (my alma mater) and the moment is completing a D.Min. degree in “Faith, Work, Economics, and Vocation. Finally, as noted above he is the founder and chair of the Center for Faith and Enterprise, the organization that published this book.

As noted above I was provided with an advanced reader’s copy of the book, so it’s possible that changes were made before publication. Nevertheless, the book as I have it seems largely complete. The fact that Tribken has been studying theology and ministry at Fuller Seminary did catch my eye. That’s because over the years I’ve seen lots of books appear that speak about faith and work, but the authors usually lack significant theological grounding. As I read The Sacred Meaning of Work I felt comfortable with Tribken’s theological acumen.

Tribken tells us in his introduction that he envisions this book to be a work of integration. In other words, he seeks to bring together theology with insight from a variety of other sources/resources including research on understanding businesses and organizations. He also draws on psychological studies as well. The goal here is to connect the sacred with the many work-related issues faced by those who inhabit everyday workspaces. Since he draws on the Bible throughout the book (he includes an appendix that lays out texts that he believes address everyday work), he recognizes that readers will come at the Bible from a variety of perspectives from traditional to non-traditional. Thus, he allows for a breadth of lenses, even as he seeks to draw on wisdom present in scripture. As many preachers understand, this isn’t easy.

Tribken begins his attempt at creating this integration of what we might think of as the sacred (faith) and the secular (everyday work). He starts this conversation in chapter one by exploring questions of human purpose, dignity, and potential using the Genesis creation stories as his conversation partner. While the role of sin might enter into what these stories have to say about human purpose, dignity, and potential, he believes that the creation stories offer a positive vision of the potential for human work. We move in chapter two from the creation stories (Genesis 1-2), wherein Tribken envisions humans being co-creators with God to a second important biblical concept. That concept is shalom. He connects shalom with flourishing in the workplace. In this context, he speaks of shalom “as holistic, multidimensional flourishing that involves spiritual, interpersonal, economic, relational, societal, psychological, and work-related aspects of our lives” (p. 23).

Tribken offers a postscript to the chapter on shalom that speaks to “the alleviation of poverty in the Bible.” He addresses several ways the biblical writers addressed poverty, including the call for anti-usury laws and the concept of Jubilee. In chapter three, the author continues his exploration of what the biblical text has to say about work, this time focusing on sin and alienation. After defining sin he explores possible responses to sin and alienation, including restoration through shalom. That conversation continues in chapter four, where Tribken addresses questions of misfortune and adversity. He acknowledges that these do not necessarily result from moral failure. Rather they can “involve spiritual and personal estrangement, either as cause or effect.” In this chapter, he addresses both burnout and interpersonal conflicts. Clergy understand both of these realities!

So, we begin our attempt at integrating faith and work by exploring creation and human dignity, then move to the vision of shalom and flourishing. In other words, the first two chapters speak about what should be. Then, in chapters three and four, Tribken speaks of what has gone wrong. That is, what disrupts this vision of dignity and flourishing. Having set this foundation, we move on to conversations about restoring the vision. This process is introduced in chapter five with a conversation about “Cultivating Character Strengths.” By that, Tribken means cultivating virtues that “help us stay spiritually grounded and act with integrity, courage, and purpose” (p. 73). Some of the character strengths he brings to the fore include self-control, diligence, the ability to receive advice, integrity, compassion, prudence, and friendship. These character strengths and others discussed in the chapter have, in his mind, a spiritual connection. It is this connection that he believes can give hope to those engaged in work.

Having defined the important character strengths that Tribken believes workers need to develop, he moves in chapter six to describe several spiritual practices that can help reinforce and develop these character strengths. These practices are centered in prayer. With that in mind, Tribken describes a variety of forms of prayer from breath prayers to the timing of prayers—including praying in preparation for a meeting or difficult conversation. The goal is to integrate these practices into one’s daily work life to add meaning and purpose to one’s life. While he acknowledges the importance of becoming more productive in one’s work-life, the goal here is “to help us turn our attention toward God, with all this means for our spiritual journey” (p. 133).

To this point, we’ve addressed creation, shalom, sin, and alienation, developing character strengths, and integrating spiritual practices into one’s work life. Now we’re in a position to ask the question of whether work can be a calling. As we consider this question it is worth remembering that not all jobs are the same. Some jobs can be downright demeaning and dehumanizing, so we need to be careful in thinking about work as a calling. That said, when we think of work as a calling, we usually envision engaging in something that we feel we’re meant to do and that is in some way useful not only to ourselves but to others as well. So, how does Tribken understand work as a calling? In chapter seven, he speaks of calling in multi-dimensional terms “that reflects our human desire for meaning and purpose. It is grounded in our desire to help other people and contribute to the greater good and—for most of us—to connect with something deeper or larger than ourselves, with God, and to reflect this in our lives” (p. 135). In other words, calling is about much more than me!

We move from the question of calling in chapter seven to matters of leadership in the eighth and final chapter. In this chapter, Tribken explores the “Spiritual Dimensions of Leadership.” In doing this he contrasts leadership with management. Being a leader is different from being a manager. As I read this, I would say that Tribken wants to lift up leadership, even as he recognizes that not everyone is called to be a leader. He also recognizes that organizations need both leaders and managers. In this case, he wants to lift up the importance of being a leader. Because of the challenges and temptations facing those who are leaders, he notes that to be a leader requires “a considerable degree of spiritual maturity.”

The eight formal chapters of The Sacred Meaning of Everyday Work are followed by four appendices. These focus on “Work in the Bible,” Work in the Twenty-First Century,” “Spirituality and the State of Flow,” and “The Opportunity for Churches.” I want to focus on the fourth appendix because I think this brief piece needs to be read by clergy so that they might better understand how to speak to work issues faced by their parishioners, whether that involves sermons, guest speakers, or other events (Bible studies). As such, I believe that The Sacred Meaning of Work even has value for those of us who are engaged in ministry in the church, so that we too might engage in shalom ministry with those engaged in everyday work.

In closing, I will admit that I agreed to read The Sacred Meaning of Everyday Work with a bit of skepticism. It’s easy to write a book that seeks to integrate faith and work relying on proof texts and pop psychology. That is not what I found. Instead, I found a resource that can assist those who go to work every day to integrate their faith with their labor so that they might do so with integrity, compassion, and grace. While it isn’t the primary focus of the book, Tribken acknowledges that many jobs are less than humane. Addressing that reality is a different book, but he does understand the reality that jobs can be dehumanizing. So, in a final analysis, I will say that this is a compelling book that speaks to the church and to those in the Christian community who engage in work, whatever its nature. That is good news because most of us will spend a significant part of our lives at work.

This review originally appeared on BobCornwall.com.

Robert D. Cornwall is an ordained minister in the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ). Now retired from his ministry at Central Woodward Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) of Troy, Michigan, he serves as Minister-at-Large in Troy. He holds a Ph.D. in Historical Theology from Fuller Theological Seminary and is the author of numerous books including his latest “Second Thoughts about the Second Coming: Understanding the End Times, Our Future, and Christian Hope” coauthored with Ronald J. Allen. His blog Ponderings on a Faith Journey can be found at www.bobcornwall.com.