There’s a “prominent” new memorial on the campus of Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Kentucky. At least that’s how the school’s president, Al Mohler, described the small plaque near the entrance of the campus chapel. Others remain unimpressed.

The four founders of the seminary in 1859 each enslaved Black people, and two of them soon afterward served in the Confederate Army. Their names appear prominently on campus, including on the chapel and the library buildings. And the enslaver founders have also been featured on campus memorabilia like coffee mugs. So in 2020, as statues to Confederate generals and enslavers were being toppled by protesters and removed by governments across the U.S. and in other countries, some Black pastors called on Mohler to similarly remove the honors to the enslavers who started the school.

Mohler refused, but he told one Black pastor, Rev. Dwight McKissic, that he would erect a memorial to those enslaved by Southern. When that pastor visited campus recently, he couldn’t find it. So Mohler made the announcement on Twitter that it really did exist.

“Sorry you did not see the memorial,” Mohler tweeted in response. “It is quite prominent. You had suggested it, and we followed up as promised. Your suggestion was right and timely. If you have time to come back, I will gladly show it to you this afternoon.”

Because of that tweet, another pastor went looking for it. It turned out to be just a plaque next to the chapel that is named for an enslaver. Another Black pastor quickly questioned the notion of its prominence.

“I’m no scholar but prominent seems to be somewhat of a stretch in my estimation,” tweeted Rev. Derek Hayes, pastor of The Committed Church in Louisville. “Again, I’m no scholar. Neither am I dummy and the very placement of this plaque proves at the very least that @albertmohler is either culturally insensitive or ignorant. The founders aren’t heroic!”

In Southern’s report in the SBC’s Book of Reports released in May, the school again said it would not remove the honors to enslavers. But the report added that they “have recognized the moral reckoning to which we are called by establishing a major marker on the campus which acknowledges the sin of American slavery and the contributions made to this institution by countless slaves.”

Not only does the small plaque not seem “quite prominent” or “major,” it’s also odd that there wasn’t a more official announcement about it. Was there an unveiling? Did Mohler speak? The seminary didn’t respond to my requests for comment about the plaque and its installation. Additionally, the alleged memorial to the enslaved manages to name (and praise) the founders but not any of the enslaved people.

“Our founding faculty, James P. Boyce, John A. Broadus, Basil Manly Jr., and William Williams gave this institution its birth and devoted their lives to its cause. They were also slaveholders and defenders of slavery,” the plaque reads. “Together, they claimed ownership over at least fifty fellow human beings, equally made in God’s image. We do not know their names, but God does. We now honor and express gratitude for their unrecognized contribution to this Seminary and its mission.”

Campus of Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Kentucky.

To call forced labor a “contribution” is akin to thanking a robbery victim for their gift to the person who assaulted them. And the notion of not knowing the names of the enslaved isn’t fully accurate.

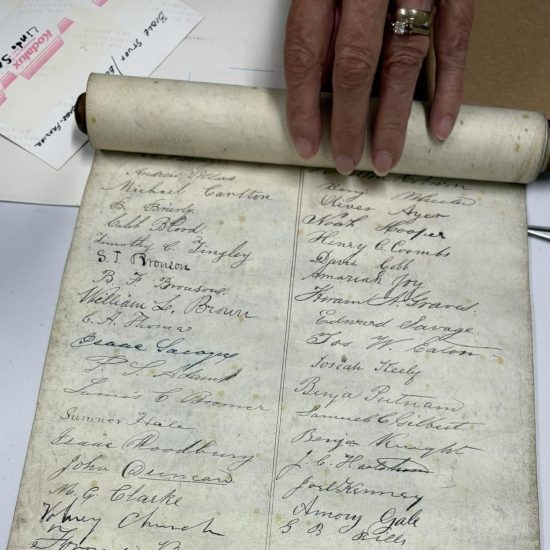

While it is true that many of the names are likely lost to history, we do actually know some of the names of those enslaved by Southern’s founders. In fact, one of them is even named in Southern’s 2018 report documenting the slavery ties and racist writings of its founders and early professors and trustees. Ben, a man enslaved by one founder, is mentioned six times on one page in that report. Additionally, as I noted in a column in 2020, a couple who were enslaved by another founder are mentioned but not named even though the source cited for the story does provide their names: George and Fanny. Other names could likely be uncovered and might even already be in the research Southern compiled for its historical report.

But like the plaque, the report focuses on the enslavers instead of the enslaved. While the 71-page report in 2018 includes just six named references to any enslaved persons, it references the founders by name over 380 times. And an eight-page report by Mohler in 2020 as he urged trustees not to remove the names of enslavers from campus buildings does not name any of the enslaved but does name the four founders a total of 55 times. Now, the “prominent” and “major” plaque names all four founders but not a single person enslaved. It’s clear who is really being honored.

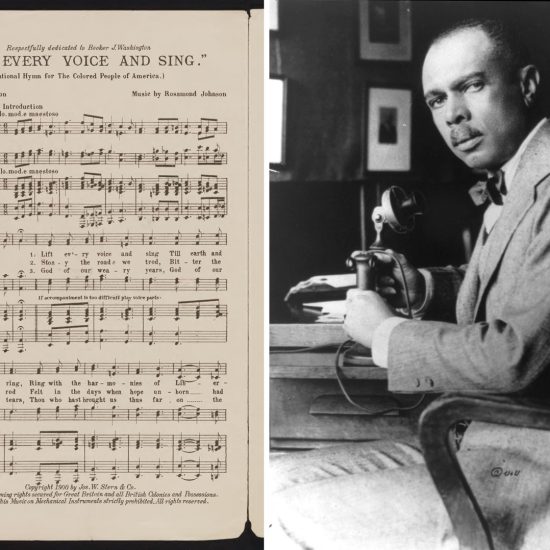

As I argued in that 2020 Word&Way column, Mohler and Southern need to say the names of the enslaved people. It’s a powerful split from how many official documents from the time of slavery skipped the names of enslaved persons because they were allegedly just property. And it’s a meaningful corrective to how we have often erased enslaved individuals from history.

“That’s precisely why saying the names of the enslaved can serve as a powerful rebuke to the system of White Supremacy that birthed SBTS,” I wrote. “Saying the names of the enslaved testifies to their God-given human dignity. Saying their names signals we won’t join their enslavers in attempting to erase their lives from history.”

In the piece, I thus urged Mohler to learn more names of the enslaved persons and say them during events at Southern, name places on campus after the enslaved, and “construct a memorial on a prominent campus location.” Not a little plaque on a wall, but an actual memorial. Moher apparently didn’t take my advice (this was less than three months before he called me a “liberal nitwit” because of a different Word&Way column I wrote).

Instead, Mohler’s shown himself philosophically and theologically unequipped for the moral reckoning with history that is needed. Other schools with similar slavery ties are showing a better way. So this issue of A Public Witness visits Christian and public universities who are actually honoring those enslaved by their founders with major memorials in prominent locations on their campuses. These memorials provide a guide for Southern and others to think more seriously about what it means to give honor.

The rest of this piece is only available to paid subscribers of the Word&Way e-newsletter A Public Witness. Subscribe today to read this essay and all previous issues, and receive future ones in your inbox.