VATICAN CITY (RNS) — The Rev. James Martin, an American Jesuit priest who has championed the cause of the Catholic LGBTQ community, said he intends to use his appointment as a representative to the upcoming Synod on Synodality in Rome as a chance to bring more attention to LGBTQ experiences.

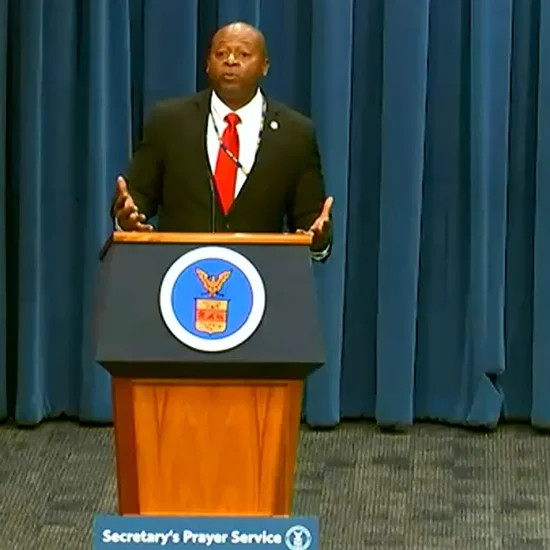

The Rev. James Martin at the Vatican in a scene from the documentary “Building a Bridge.” Photo courtesy of Building a Bridge

But in an email interview on Tuesday (July 11), Martin, the founder of Outreach, a group that promotes inclusivity and welcome for LGBTQ Catholics in the church, said that listening at the synod will be just as important as speaking. “It’s a two-way street,” said Martin. “I hope, if possible, to be able to be one of the voices for LGBTQ people; and at the same time, I hope to listen to voices in the church that I have perhaps not heard before,” he said.

The gathering of bishops, whose theme is “Towards a Synodal Church: Communion, Participation, and Mission,” is the culmination of a worldwide, multiyear consultation of Catholics in parishes, bishop’s conferences, and continental assemblies and will take place Oct. 4-29 at the Vatican. A second meeting will follow in the fall of 2024.

The synod will address topics ranging from church hierarchy and female leadership to LGBTQ inclusion. For the first time in church history, the synod will include a large number of Catholic lay and religious who will have a right to vote on these topics alongside the bishops.

The Vatican released the list of participants on Friday. Most were nominated by bishop’s conferences and religious organizations, with some selected directly by Pope Francis. Martin said he was “honored and surprised” to be invited by the pope.

The question of LGBTQ inclusion was among the questions and reflections of the Instrumentum Laboris, a document summarizing the discussions held by Catholic faithful around the world in preparation for the synod that will serve as a guide for synodal discussions.

“For many LGBTQ people, so long accustomed to not even being mentioned — far less listened to — this was an historic step forward,” Martin said. “As such the Synod has been, in a church of light and shadow for LGBTQ people, a definite light.”

In his ministry, Martin has experienced a significant degree of backlash for his advocacy for LGBTQ members of a church that officially condemns homosexuality. At the synod, he will likely be sitting next to some of those critics, who include some high-ranking clergy. “As ever, I think that the best way forward is simply to share stories, and to tell of the ‘joys and hopes and griefs and anxieties,’ to quote Vatican II, of this community,” Martin said.

The synod is being considered by many a sequel to the Second Vatican Council, the synod that met from 1963 to 1965 and sought to reconcile the Catholic Church with the fast-changing realities of Western society at the time. Today the church faces new challenges as society’s understanding of religion, technology, and sexuality continues to evolve quickly.

Martin admitted that some “far-right” Catholics, who “seem dead set against the synod,” may be resistant to hearing stories from their LGBTQ counterparts. But he said he holds out hope that “by seeing so many people coming together from a variety of countries and backgrounds — including some well-known figures on the ‘right’ — even critics might think, ‘Maybe there is something to listen to here.’”

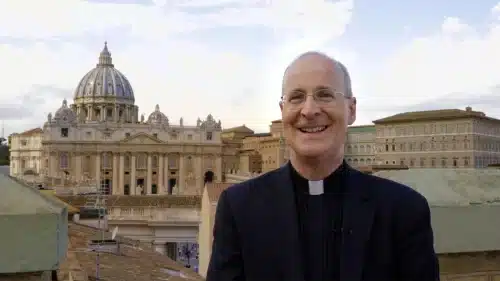

The synod will be attended by nonvoting “experts and facilitators” whose role is to help guide the discussions. Among them is the Rev. David McCallum, another Jesuit priest. McCallum directs the Discerning Leadership Program, which instructs lay and religious members of the church on how to engage in a synodal style of leadership. Some of the other facilitators have also gone through his program.

Instead of sitting before a speaker, synod participants will sit at round tables in Paul VI Hall at the Vatican to listen to speeches before breaking into working groups. in an interview with Religion News Service, McCallum compared the dynamics of this synod to a dance that moves attendants from the general assembly to individual conversations, from the public speeches to watercooler chats. This flow should inspire a sense of intimacy and understanding among those attending the synod, he explained.

“The space has to be hospitable and open to marginalized voices, for people who feel their experience has not been heard and welcomed in the church,” McCallum said. “To make that a fact and not an intention is of critical importance.”

McCallum will act as a kind of “synod sherpa,” he said, keeping participants on track in their sessions and “holding space” for open conversations in a way that acknowledges the sacredness of the synodal meeting.

“I wouldn’t be surprised if really strong tensions emerge. I think that is the intention of the synod,” said McCallum. “The role of a good facilitator is to hold and frame the tensions so they can be generative and not destructive.”

He will guide participants to first speak from their own experience and prayer, then listen to others with intention, and lastly discern what consensus emerged from the discussions.

When it comes to polarizing topics such as inclusion or access to Communion, McCallum said, “the fear people have is that the other side will carry the day and things will go too far and what we hold precious will somehow be lost.” What they forget, he said, is that creating new spaces for discussion “can be a very invigorating creative exercise.”

While the synod can “feel like a roller-coaster sometimes,” McCallum said, “it’s about helping people be patient with processes even when people really want to get to outcomes.”