(RNS) — Fewer Christians fleeing persecution in their native countries have found a safe harbor in the United States in the past half decade, according to a new report from a pair of Christian nonprofits, which cites the effects of the pandemic and the dismantling of U.S. refugee resettlement programs during the Trump administration.

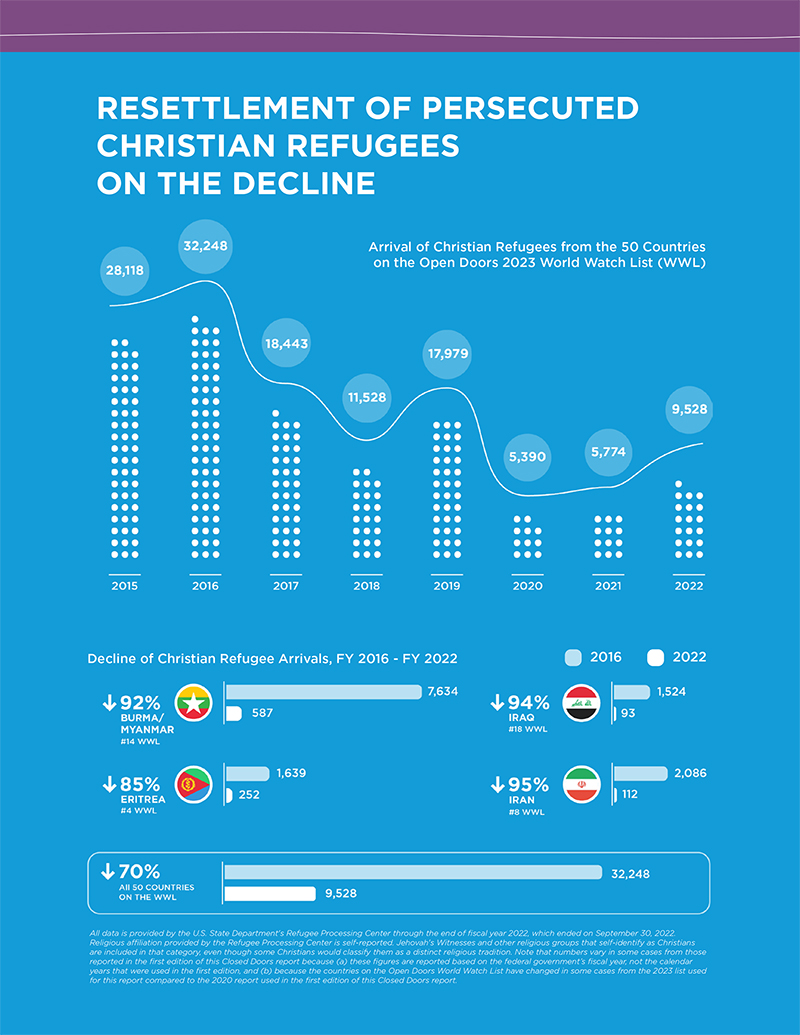

The report, titled “Closed Doors,” found the number of Christians coming to the U.S. from countries named on a prominent persecution watchlist dropped from 32,248 in 2016 to 9,528 in 2022 — a decline of 70%.

Cover of the “Closed Doors” report in Sept. 2023. Courtesy World Relief and Open Doors

The number of Christian refugees from Myanmar dropped from 7,634 in 2016 to 587 in 2022, while the number of Christian refugees from Iran dropped from 2,086 in 2016 to 112 in 2022. Christian refugees from Eritrea dropped from 1,639 in 2016 to 252 in 2022, while refugees from Iraq dropped from 1,524 to 93 during the same timeframe.

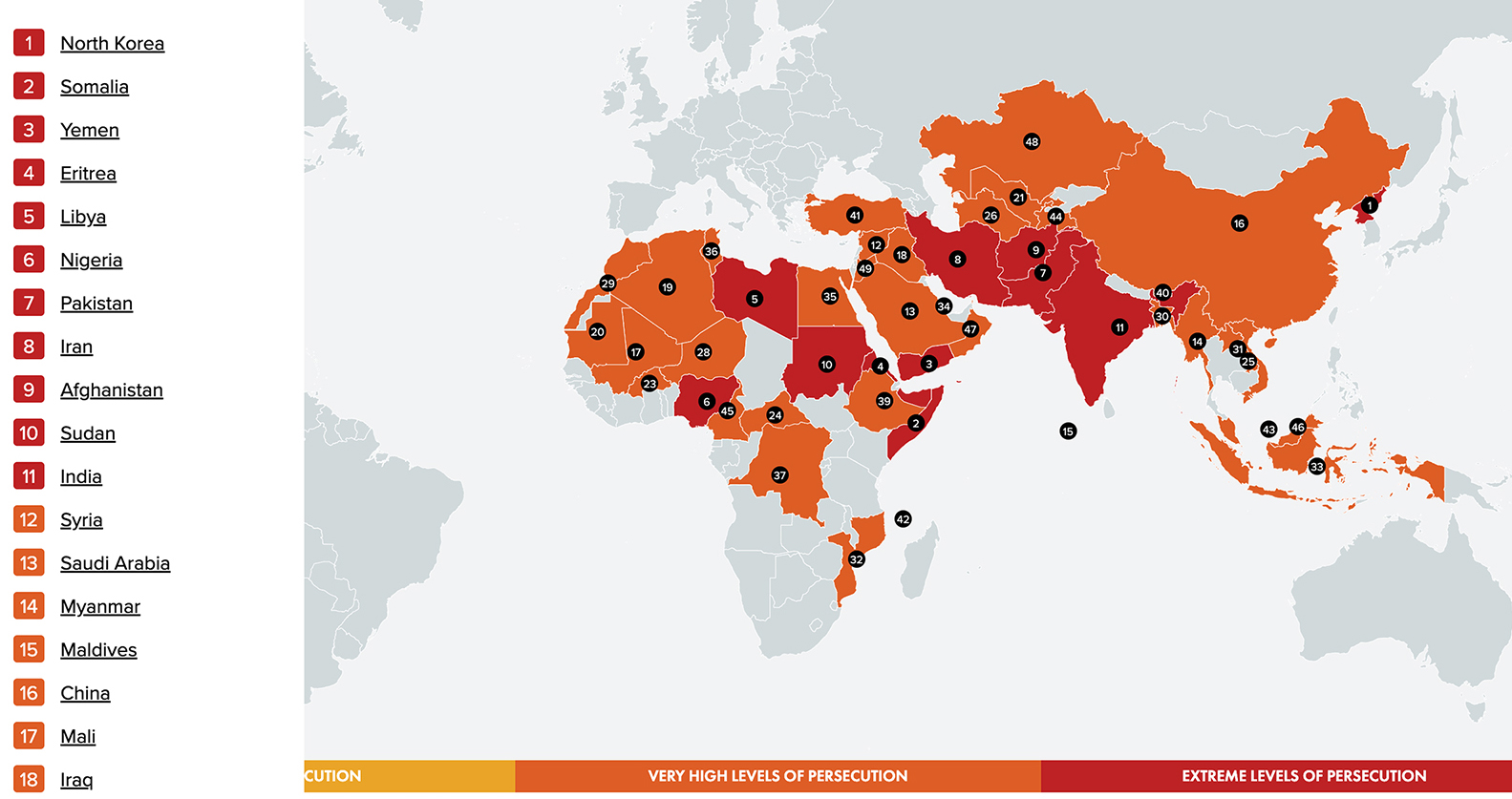

All four countries are among the 50 nations on the annual World Watch List published by Open Doors, an international Christian charity that tracks persecution. The new report was written by Open Doors and World Relief, an evangelical charity that resettles refugees.

“The tragic reality is that many areas of the world simply aren’t safe for Christians, and Christians fleeing persecution need a safe haven in the United States,” according to the report.

The decline in Christian refugees comes at a time when the persecution against Christians is on the rise, said Ryan Brown, CEO of Open Doors.

“Resettlement of Persecuted Christian Refugees on the Decline” Courtesy World Relief and Open Doors

According to the Watch List released earlier this year, some 360 million Christians face what Open Doors calls “high levels of discrimination and persecution.” That’s up from 260 million reported in a 2020 edition of the “Closed Doors” report. Much of the increase has come in sub-Saharan Africa, he said, driven by political instability and internal conflict in countries like Nigeria.

“Tragically, that’s the area where we are seeing the most intense violence as it relates to persecution,” said Brown.

According to Brown, many Christians in countries where there is persecution want to stay there, often feeling called to minister in difficult situations. But some are forced to flee.

In 2016, according to the “Closed Doors” report, 32,248 refugees from countries on Open Doors’ World Watch were resettled in the United States. That number dropped to 11,528 in 2018 and then to 5,390 in 2020.

While persecution is on the rise, both the annual refugee ceiling set by the U.S. president each fall and the total number of refugees resettled yearly in the U.S. have dropped. In 2016, according to the “Closed Doors” report, about 97,000 refugees were resettled. That number declined to just under 23,000 in 2018. Canada, despite having a much smaller population, managed to resettle about 28,000 refugees that year.

“In the calendar year 2020, the U.S. resettled fewer than 10,000 refugees for the first time in the resettlement program’s history,” according to the report.

The lowering of the refugee ceiling began under President Trump, and the sudden drop, exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, dismantled much of the infrastructure needed to resettle refugees, including the work done in the United States by a number of faith-based groups, including World Relief, Church World Service, and HIAS, the latter founded as the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society.

In 2021, President Biden set the refugee ceiling at 15,000 — the lowest since the passage of the 1980 Refugee Act, which sets the parameters for the current refugee resettlement system. That ceiling was later raised to 65,000 after faith groups protested.

This past year, the ceiling was set at 125,000 — however, the U.S. only resettled about 60,000 refugees in fiscal year 2023, according to the “Closed Doors” report.

That shortfall is due in large part to the aftereffects of the pandemic, said Matt Soerens, vice president of advocacy and policy at World Relief. The screening process for refugees, which takes years, was shut down during the pandemic and was slow to restart.

World Relief, which has resettled just over 7,000 people during the past year, including refugees from Afghanistan and Iraqis with Special Immigrant Visas, and the other resettlement agencies closed down offices and laid off staff when the refugee resettlement program shut down. Restarting those offices and adding staff has taken time as the agencies rebuild their domestic infrastructure.

“We are expanding,” he said. “I wish I could have the confidence to expand even more, but it’s very expensive to raise the space and hire staff and then have to lay them all off three years later.”

Calling the resettling of 60,000 refugees a sign of progress, Soerens credits the Biden administration with helping the agencies to rebuild the overseas resettlement infrastructure, but added, “They didn’t start nearly as quickly as we would have liked them to.”

Part of the impetus for the “Closed Doors” report, he said, was to put pressure on the Biden administration to continue that progress.

Soerens said that he hopes in the future, the refugee resettlement program will be more stable. For years, he said, the program enjoyed bipartisan support and was seen as a source of pride for American leaders — and a sign that America was living up to its ideals.

“We’ve had a history of being a refuge for those fleeing persecution for any number of reasons, among them, religious persecution,” he said. “I think that we’re at risk of losing that.”

A map of the 2023 World Watch List compiled by Open Doors. Screen grab

While the report focuses primarily on Christian refugees, resettlement groups also worry about those from minority faiths, including Jews and Yazidis, who have “largely been shut out of refugee resettlement in recent years,” according to the report.

“As Christians, we believe that all people have the right to religious freedom and that religious minorities of any sort — not just those who share our Christian faith — should be protected,” the report said.

Brown said that some of his fellow Christians may have lost sight of the importance of refugee resettlement, in part because of the current polarization over immigration and the surge of asylum seekers and migrants at the border.

They may not be aware that restricting refugees affects persecuted Christians, he said.

In the 1950s, when Open Doors was founded, the concern was mostly about religious persecution behind the Iron Curtain. The group’s late founder, Andrew van der Bijl, better known as Brother Andrew, spent years smuggling Bibles into Communist countries.

Today, said Brown, persecution continues under authoritarian regimes, but it also happens in countries where there’s internal conflict and strife. And while countries like China have experienced economic prosperity, he said, that prosperity hasn’t been accompanied by the expansion of human rights.

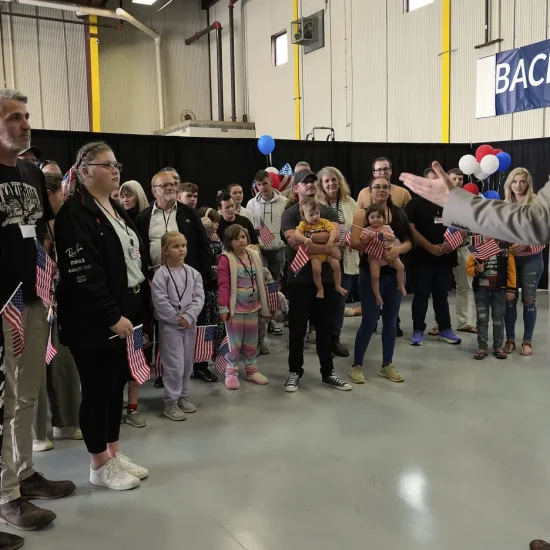

Brown hopes the report will lead Christians to pray and to assist refugees when they arrive in the United States. He also hopes they will support refugee resettlement programs.

“We’d love to see America take its place again on that global stage,” he said, “to be that beacon of freedom and religious liberty.”