SONGS I LOVE TO SING: The Billy Graham Crusades and the Shaping of Modern Worship. By Edith L. Blumhofer. Foreword by Fernando Ortega.

I will confess that I love singing hymns. Whether the hymns are new or old, it doesn’t matter, I enjoy singing. Of course, a good sermon is always welcome when it comes to worship, but congregational singing is the key to worship for me. I know that I’m not alone in this. Successful evangelists from Dwight L. Moody to Billy Graham have understood this to be true also. Moody had Ira Sankey leading the singing, and Billy Graham had Cliff Barrows and George Beverly Shea. What we might forget is that these evangelical ministries not only engaged in evangelistic/revivalistic outreach, but they also influenced hymnody and worship music. For example, if you enjoy singing “How Great Thou Art” it’s likely because the Billy Graham Crusades, mainly George Beverly Shea, made it popular. Whether we ever attended or watched a Billy Graham event, if we know and love this hymn somewhere along the way someone experienced it and brought it into the churches. It was Bev Shea who got the ball rolling.

Robert D. Cornwall

Billy Graham and his two colleagues have passed on, and many contemporary Christians may have heard of Graham but not know much about the music that accompanied his preaching. The names of Cliff Barrows and Bev Shea may no longer be well-known, but their influence continues to this day through the music they created and introduced to the larger Christian world. While they were evangelicals, the music they shared made its way into more mainline circles. For example, “How Great Thou Art” can be found in the most recent PCUSA hymnal [Glory to God] and the Chalice Hymnal [Disciples of Christ]—two hymnals I have close at hand. So, what’s the story behind the partnership between Graham and the music that marked his ministry? The answer can be found in Edith Blumhofer’s Songs I Love to Sing.

Edith Blumhoffer (1950-2020) was a well-regarded historian of evangelicalism and American Christianity, as well as serving as the director of the Institute for the Study of American Evangelicals at Wheaton College, where she also taught. Blumhofer is the author of several well-regarded biographies of leading figures in evangelical history, including Fanny Crosby and Aimee Semple McPherson. She passed away before she could complete Songs I Love to Sing, and therefore it was brought to completion by Larry Eskridge, the former assistant director of the ISAE and historian of American Christianity. While the book was essentially complete at the time of Blumhofer’s death, as Eskridge notes in his preface, it lacked her final touch. Nevertheless, Eskridge was able to bring together a very readable and important look at the role music played in the Graham ministry and Christian life in general. For that, we can be grateful.

While Billy Graham plays an important role in this story because he was the face and primary voice of the Billy Graham Crusades, he is not the focus of Songs I Love to Sing. It’s the music and the primary creators of that music who stand at the center of the story. While it was Graham who brought together the music team, he was not a musician. Thus, it was Cliff Barrows, Graham’s music director, and George Beverly Shea, his long-time soloist, who stand at the center of the story. It’s possible that Graham would have been successful in his ministry without the music, but most assuredly, he would likely not have been as successful as he proved to be. This is a word to preachers, even ones not as famous as Graham (like me) just remember that your music minister(s) are important partners in the ministry of the church.

Blumhofer notes in her introduction that Christians in every generation “sing their faith in lyrics that reflect their circumstances and music that mirrors their times.” Some hymns and songs transcend time and others are for the moment. Therefore, she writes that “Billy Graham and his associates George Beverly Shea and Cliff Barrows recognized the universal appeal and usefulness of music wedded to preaching and made it an anchor of a new and global burst of evangelical endeavor” (p. 1). Graham’s final crusade may have taken place in 2005, but his influence and the music connected to his ministry continue to this day. That is true even if new music has taken center stage. One thing we learn as we read this book is that Graham and his team adapted to new musical styles and tastes as time passed, even if the new music didn’t appeal to them. They understood that even if they were not the biggest fans of Christian rock, they recognized its value to the success of their ministry.

Blumhofer begins her story by introducing us to the three primary figures in this story: Graham, Shea, and Barrows. She begins with Bev Shea. the eldest of the three. She was already a well-known singer when the team began to form. He was a Canadian who early in life got involved in the music and radio industries. It was while he was involved in radio ministry in Chicago that he became acquainted with Torrey Johnson, the founder of Youth for Christ. It was through YFC and Johnson that he got connected to Billy Graham. The next person we meet is the evangelist himself, Billy Graham, who was a few years younger than Shea. Unlike Shea, Graham had no musical talent but like D. L. Moody before him, he understood the importance of music to the success of a ministry. Thus, he created the setting in which Shea and Cliff Barrow could work. While we might think we know Graham’s story, Blumhoffer nonetheless gives us a brief biography of Graham. What we learn is that Graham was preaching at the Village Church in Chicago when he met Shea who was a featured soloist on a Christian radio program. Graham brought Shea into his work, and a partnership was born. The final member of this trio, Cliff Barrows, was several years younger than Graham. A Californian, he had developed his musical talents, which were put to use in his church. Originally, he planned to study to be a physician, but his life took a different turn in 1937 while attending a Bible conference. It was at this conference that he felt a call to the ministry. This sense of call led to his enrollment at Bob Jones College, where he pursued a degree in music and radio work, skills that would come in handy as the years passed. After graduation, he was ordained as a Baptist minister. Then in 1945 he met Graham and quickly became part of Graham’s team as he had now become an evangelist for YFC.

The team that included Shea, Barrows, and Graham began coming together in 1946, with Barrow joining the team first. Then in 1947, Graham prevailed on Shea to join the team. This partnership would last until the very end of Graham’s ministry. We learn how Graham and Barrows began studying earlier revivals, including those of Moody and Billy Sunday, as to how music factored into these ministries. After the team was formed each member brought their own experiences to the partnership. Shea was a well-known soloist. Barrow was the song leader and choir director. Together the two guided the musical part of the ministry, working in tandem with Graham who guided the overall effort.

Once Blumhofer has introduced us to the team, detailing the gifts each brought to the partnership, she introduces us to the sources and influences on their music. She begins with the influence of religious radio on the partners. At the time Mainline Protestants owned the primary airwaves by taking advantage of free airtime. Since Mainliners controlled the free airtime offered by the major outlets, evangelicals such as Charles Fuller and others purchased airtime. The choice of music included in these broadcasts served to influence evangelical musical tastes. Among the music creators who proved influential was Herman Rodeheaver, who had worked with Billy Sunday before going on to become a major religious music publisher. Then there were the hymn writers they drew from, including Fanny Crosby, whose hymns were well known and widely appreciated, especially “Blessed Assurance.” Another hymn of note that became connected to the ministry was “All Hail the Power of Jesus’ Name.” The music chosen by the team provided a foundation for the developing ministry.

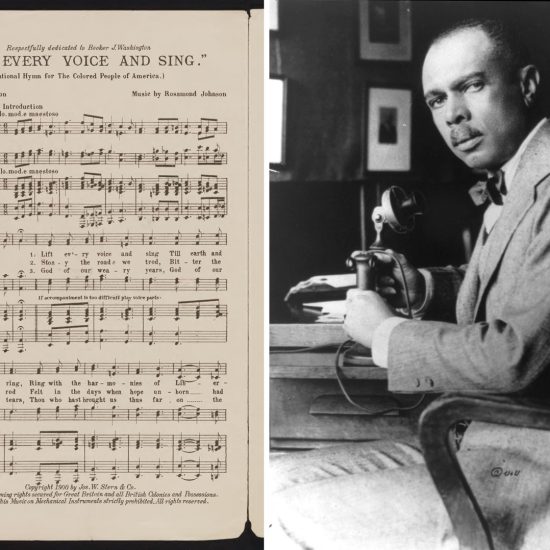

When we turn to Chapter 5, Blumhofer discusses the ministry’s theme music. That is, the songs that became especially connected to the ministry. Even people who didn’t follow Graham too closely knew the connection to Graham’s ministry of the gospel song “Just as I Am,” which provided the background for the altar calls. While many will know of that connection, we might not know how the song “How Great Thou Art,” a song beloved in many mainline churches, was introduced to the world through the ministry. The form that most of us know, the form present in many Mainline hymnals, was introduced in 1955 by George Beverly Shea in 1955 (an earlier version was introduced in 1954). I expect many will be as interested as I was to read Blumhofer’s brief history of the song that has Swedish origins in the 1880s and that found its central place in Graham’s ministry at the 1957 crusade at Madison Square Garden.

After introducing us to the members of the team, along with the influences and music sources, including the theme music such as “Just as I Am” and “How Great Thou Art,” Blumhofer introduces us to the guest voices in Chapter 6. While Barrows was the song leader and choir director (mass choirs were an important part of the events), and Shea offered his solos, they were not the only musical elements of the events. The team chose to include a variety of musical talent that not only graced the event with their music but served as witnesses to the work of God in their lives. These folks were often local figures. But they also drew on nationally known talent such as Roy Rogers, Dale Evans, and Johnny Cash. They also tried to bring diversity to the stage in the form of guest voices. Thus, the crusades would feature African American singers such as Mahalia Jackson and Ethel Waters, and many others. They also introduced younger performers such as Michael W. Smith and Amy Grant to a wider audience, even if Barrows and Shea weren’t big fans of more contemporary Christian music.

We see this movement into more contemporary Christian music in Chapter 7, which is titled “Translation.” Blumhofer discusses here Graham’s realization that musical tastes had begun changing in the 1960s. While rock music might not be the kind of music that the trio embraced, they began to understand that they needed to find ways of including it in their services. Thus, it is in this chapter that we learn of the various ways in which Graham either partnered with others or created places within his evangelistic ministry for newer forms of music from Amy Grant to DC Talk. By the late 80s and into the 90s, they began to look for ways of creating different forms of events, where concerts took center stage, while Graham’s messages became shorter, taking on the guise of advice from a grandfather. Overall, these seemed successful.

Using an appropriate music term— “Coda” —Blumhofer brings Songs I Love to Sing to a conclusion by focusing on the final Billy Graham Crusade in 2005, which was held in Flushing Meadows, not far from Madison Square Garden where his 1957 Crusade “cemented Graham’s position as the nation’s preeminent evangelical voice and introduced the nation—and the world—to Bev Shea’s iconic rendition of ‘How Great Thou Art’” (p. 149). While Graham has come under criticism in recent years for his ministry, some of which has been well-deserved, he was also attentive to the changing times. That is reflected in the music and the performers of the Crusade. Once again, it’s important to remember that this is not a book about Graham’s evangelistic work, but rather the role music played in his ministry, as well as the influence of that music on the larger Christian community.

I expect that this study of the role of music in Graham’s ministry will be of interest to many in the church whether they are music professionals or lay persons. Church choir directors might find this quite interesting, as they discover how certain songs made their way into the mainstream. When it comes to clergy, this serves as a reminder that our sermons will reach more ears and hearts if partnered with the music of the church. The person who provides this introduction to the role of music in this ministry and beyond, Edith Blumhofer, before her death possessed both the scholarly and story-telling ability to make Songs I Love to Sing a compelling resource.

This review originally appeared on BobCornwall.com.

Robert D. Cornwall is an ordained minister in the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ). Now retired from his ministry at Central Woodward Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) of Troy, Michigan, he serves as Minister-at-Large in Troy. He holds a Ph.D. in Historical Theology from Fuller Theological Seminary and is the author of numerous books including his latest “Second Thoughts about the Second Coming: Understanding the End Times, Our Future, and Christian Hope” coauthored with Ronald J. Allen. His blog Ponderings on a Faith Journey can be found at www.bobcornwall.com.