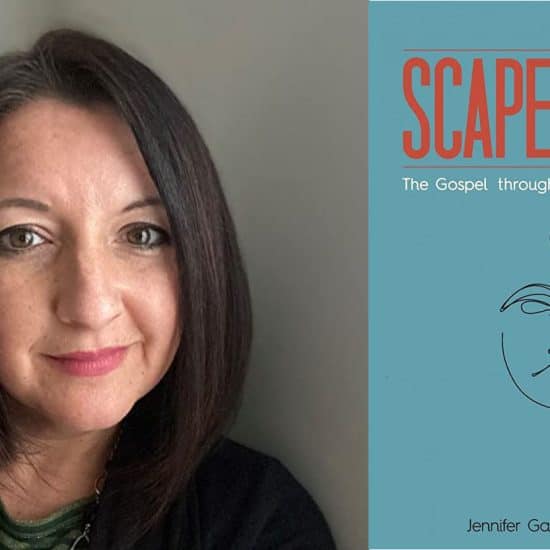

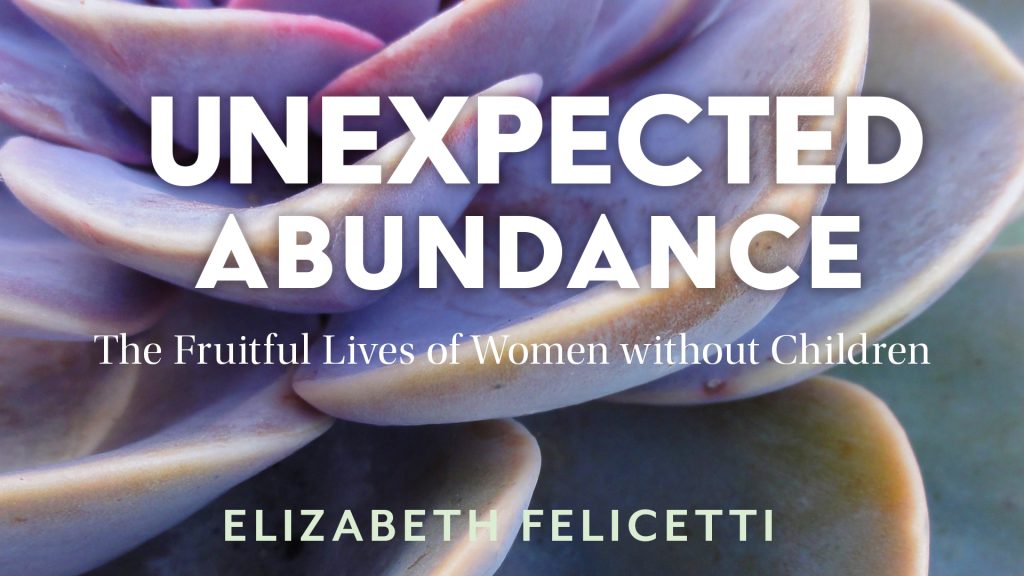

UNEXPECTED ABUNDANCE: The Fruitful Lives of Women without Children. By Elizabeth Felicetti. Grand Rapids: MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2023. Xii + 163 pages.

If we read carefully through the Bible, we will come across stories of “barren” women. That is, we encounter stories about women who for some reason are unable to produce children. In the ancient world that was a problem because it was important for women to bear children. This was their duty in life. Therefore, we encounter Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel, Hannah, Elizabeth, and others who seem unable to conceive. However, in all of these cases, God made a provision for them to bear children who proved important to the biblical story. Then and now, one solution to “barrenness” was surrogacy. Sarah used Hagar, while Rachel and Leah also used surrogates to expand the family. For a contemporary conversation about surrogacy, one might turn to Grace Kao’s book: My Body, Their Baby: A Progressive Christian Vision for Surrogacy. Despite societal pressure for women to bear children, is having a baby necessary for a woman to live a fulfilled life? Might a woman live an abundant life of service that is made possible by not having children? It’s a question that requires careful exploration.

Robert D. Cornwall

Elizabeth Felicetti’s Unexpected Abundance makes the case biblically and historically, as well as contemporarily, that women can live fruitful lives without children. She does so from personal experience. Felicetti is an Episcopal priest who tried for a decade to conceive but did not have a child. What she offers here is an invitation to look at the many women in Scripture and through history who lived abundant lives and made great contributions to the work of God in the world. In this book, Felicetti essentially seeks to reclaim the word “barren.” She does this by looking at the desert, which at first glance might seem barren, that is it might seem to be lifeless, but is full of life. What we have here is a book written by a woman who wanted to have children but ended up not having children. While she could have gone to extraordinary lengths to conceive, in the end, she chose not to go that route. This was her choice, understanding that other women might make other choices. What Felicetti seeks to do in this book is offer women without children (and really men as well) a word of encouragement. She wants them to know, whether by choice or not, one can experience extraordinary abundance without producing children.

In the course of Felicetti’s book, Extraordinary Abundance, we encounter the stories of biblical women such as Hannah and Rachel, as well as women like Mary and Martha. While Hannah and Rachel are given sons, we’re never told of the marital status of the sisters Mary and Martha or whether they had children, but the silence of scripture invites us to ponder the question. Along the way, we also encounter stories of medieval mystics, English religious reformers, composers, activists, medical professionals, and clergy. Each of the women discussed never had children but they made extraordinary contributions to the wider world.

Felicetti begins her book by meditating on the fruitfulness of the desert as a way of reclaiming the word barren (Chapter 1). She tells us that she grew up in Arizona, where the “desert burned into my soul.” She suggests that people who think of deserts as being lifeless haven’t spent any time in them. As for women without children, they may be called barren, but that doesn’t mean they are without life.

With that meditation on the desert as a foundation, in Chapter 2, Felicetti turns to discuss the lives of “Barren Old Testament Matriarchs.” Instead of focusing on Sarah and Rachel, Felicetti introduces us to Moses’ sister Miriam, a prophet and worship leader. She lifts up Deborah, a judge and warrior, who served as a leader of the people of Israel in time of war. There’s also Esther, who risked her life for her people. Then there’s Huldah the prophet who interpreted Scripture for Josiah. Yes, she was the one Josiah turned to after the high priest discovered what many believe to be Deuteronomy. Felicetti writes that “these childless women were warriors and prophets, saviors and poets, matriarchs and liturgists. Yet women in church pews have heard and continue to hear more about biblical women as mothers or women yearning to be mothers. Women can be all of these things” (p. 33). Though these women discussed do not appear to have children, they too are matriarchs of the faith.

In Chapter 3, we move from the Old Testament to the New Testament. Here Felicetti reminds us that Jesus didn’t have children (despite the tale spun by Dan Brown in the DaVinci Code). Indeed, in the Gospel of Luke Jesus tells the woman who shouted at him that the womb that bore Jesus was blessed, that the ones who are blessed are the ones who hear the Word of God and obey it. With that in mind, Felicetti emphasizes chosen families over biological ones. She begins with the story of Mary and Martha, whom she speaks of as being wise leaders and prophets. There is also the Samaritan woman at the well who is an evangelist. The way that story is told suggests that this woman might have been caught in a series of levirate marriages. I had never thought of that possibility, but it makes complete sense. Here is a woman forced into a series of marriages to produce a child, but that doesn’t happen. Yet, because of her encounter with Jesus, she becomes an evangelist. Finally, there is Mary Magdalene, an evangelist and apostle. Each of these women does not appear to have children, and yet they were generate in life without bearing children.

We move from the biblical stories to church history in chapters four and five. These chapters and the ones that follow focus on specific women and their vocations. Chapter 4 introduces us to several medieval mystics and writers including Clare of Assisi, Julian of Norwich, and Catherine of Siena. She says of these women that “in a time period when enormous pressure was exerted to marry and procreate, these women chose to serve God by prayer, Christian leadership, and writing, and their fruits have come down to us in ways they may not have had they acquiesced to a more traditional path” (p. 58). After she lifts up the lives and influences of these medieval mystics whose writings and life stories continue to influence modern Christians, she spends Chapter 5 exploring the lives of two English religious reformers, Queen Elizabeth I and Lady Jane Grey, who was queen for nine days and later was executed. Both women played important roles in the English Reformation. It’s worth remembering here that Felicetti is an Episcopal priest, but these women who for different reasons did not bear children have left an important legacy.

After taking up these stories from history that focus on mystical writers and religious reformers, she turns to a specific vocation, that of composer. Interestingly she chooses to lift up one from the medieval world and one from the modern world (Chapter 6). These two composers are Hildegard of Bingen and Dolly Parton (yes Dolly Parton, the mother to 3000 songs). Her discussion of Dolly Parton may surprise many readers, but also be of great interest. Felicetti writes that “both powerful women had to contend with sexism yet created significant fruit despite not having children” (p. 82). From these two composers, we move in Chapter 7 to three activists: Sister Helen Prejean—the advocate against the death penalty known from the depiction of her in Dead Men Walking —along with Rosa Parks and Dorothea Dix. Parks is, of course, a civil rights icon, while Dix is known for her work addressing the issue of America’s mental institutions.

Chapter 8 introduces us to several childless medical professionals. These include the Blackwell sisters who were among the first women to earn medical degrees and become physicians. Then there is Florence Nightingale. These women were pioneers in health care and made a difference without having children. Finally, in Chapter 9, Felicetti introduces us to several childless women clergy. Being that she is an Episcopalian, she chose to focus on three Anglican women who were pioneers as clergy., These include Florence Li Tim-Oi, who was the first Anglican woman to be ordained. While that largely occurred because there was a shortage of priests in China during World War II, and her ordination was considered to be irregular, she is honored as the first to be ordained. The reason she was ordained at the time was due to her faithfulness in the face of adversity. The second woman is Pauli Murray, an African American woman, who began her work as an activist before becoming one of the first women ordained as an Episcopal priest. Finally, Felicetti introduces us to Barbara Harris, the first woman ordained as a bishop within the Episcopal church. Again, all three women were childless and yet they served their church fully.

Felicetti began this attempt to reclaim the word barren by lifting up in Chapter 1 the often-invisible liveliness of the desert. She brings Unexpected Abundance to a close in Chapter 10 by returning to the desert. then the final chapter (10), Felicetti takes us back to the desert, reminding us again of the fruitfulness of what might appear at first glance to be barren (lifeless). Thus, she concludes, speaking of the desert, “If this fruitful, fierce landscape is ‘barren,’ then I proudly claim that title” (p. 142).

Life is complicated. Yet, whatever the situation in life we find ourselves in, we can be fruitful. As the reviewer of this book, I am a married straight male who, with my spouse, produced one son. Whether he marries and his children is not yet known. I approached this book with an openness, acknowledging that people make different choices. When it comes to having children, not having a child does not mean that one’s life is not fruitful. In fact, the stories revealed here in Extraordinary Abundance suggest that women can lead fruitful lives without having children. They may, as Elizabeth Felicetti, be barren, but they are not lifeless. So, whether we have children or not we can lead abundant and fruitful lives, whatever our vocation. Thus, in her book Extraordinary Abundance, the Rev. Elizabeth Felicetti, the rector of St. David’s Episcopal Church in Richmond, Virginia, invites us to embrace our situation in life and live that life to its fullness.

This review originally appeared on BobCornwall.com.

Robert D. Cornwall is an ordained minister in the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ). Now retired from his ministry at Central Woodward Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) of Troy, Michigan, he serves as Minister-at-Large in Troy. He holds a Ph.D. in Historical Theology from Fuller Theological Seminary and is the author of numerous books including his latest “Second Thoughts about the Second Coming: Understanding the End Times, Our Future, and Christian Hope” coauthored with Ronald J. Allen. His blog Ponderings on a Faith Journey can be found at www.bobcornwall.com.