(RNS) — Americans looking to understand the ways political polarization has defined U.S. voting patterns need look no further than the divisions in the United Methodist Church.

Five years after allowing churches to leave with their properties if they disagreed with the direction the denomination was heading on human sexuality, the results of the split are in, and they reflect larger political patterns to a substantial degree.

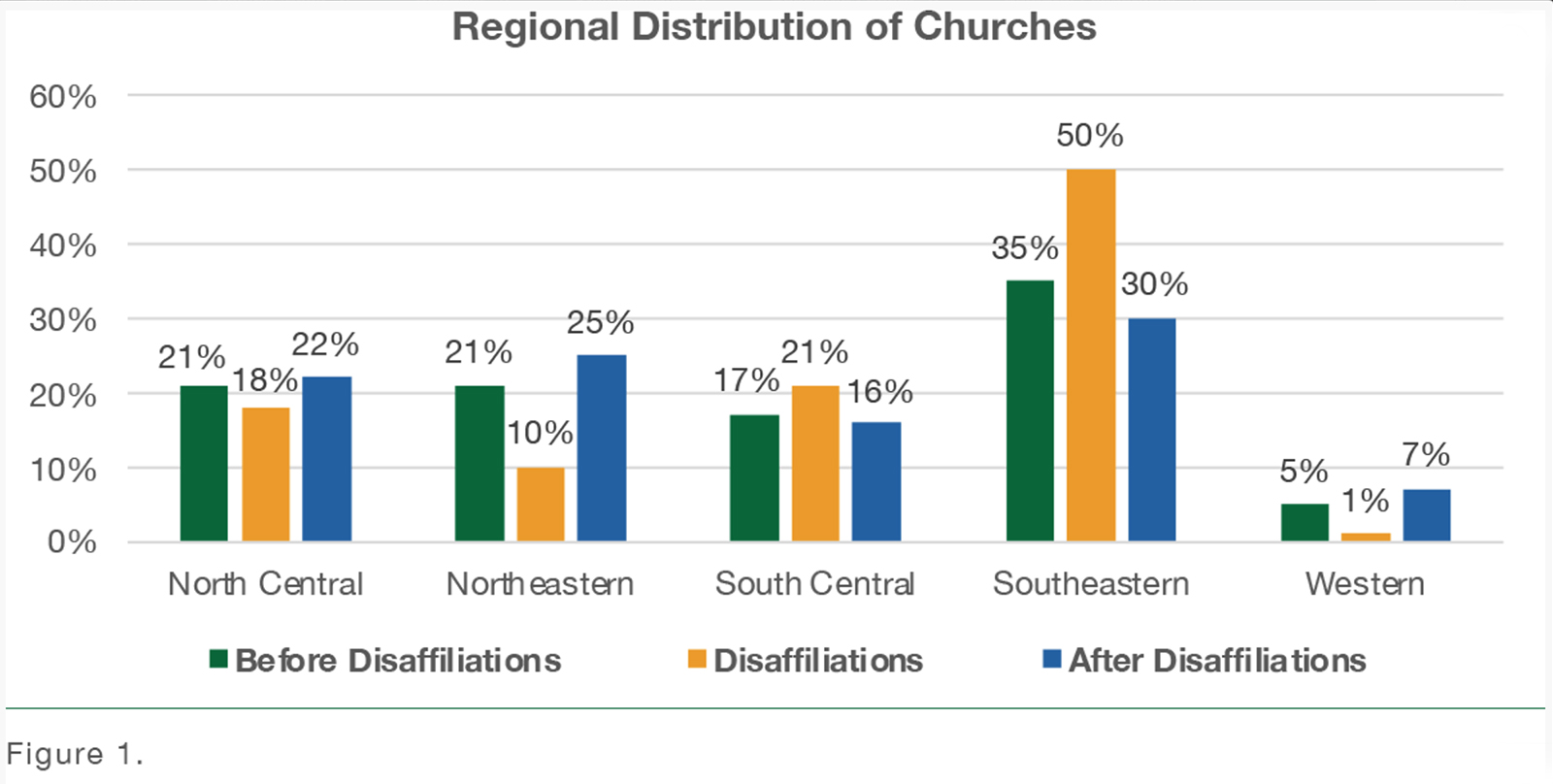

A new study by the Lewis Center for Church Leadership at Wesley Theological Seminary finds that the nation’s second-largest Protestant denomination lost a quarter of its total churches between 2019 and 2023. Leading the way were churches in the South — the same area of the country that tends to be the most politically conservative and Republican-leaning.

A whopping 71% of all disaffiliating churches came from the Southeast and South-Central regions, called jurisdictions, the study found.

“Our church has always been very reflective of the mood of the country, being a denomination in large measure of small-membership churches that reflects the culture out of which they’re located,” said Bishop Thomas Bickerton, president of the church’s Council of Bishops. “That Southeast sector of our church is very reflective of the country in terms of more conservative theological approaches to ministry.”

“Regional Distribution of Churches” (Graphic courtesy Lewis Center for Church Leadership)

Churches in these regions did not want to see the denomination loosen its rules to allow the ordination and marriage of LGBTQ people. In addition, the study found, some left for other reasons. They were wary of denominational hierarchy and far-away institutions that required annual contributions to fund the work of the denomination, preferring local autonomy and independence.

A little more than half of the 7,631 departing United Methodist churches chose to affiliate with the Global Methodist Church, the splinter group formed in 2022 as a more theologically conservative alternative. The Global Methodist Church now has 4,495 member congregations, of which 4,300 are in the United States, its transitional officer said. Many others chose to become non-denominational.

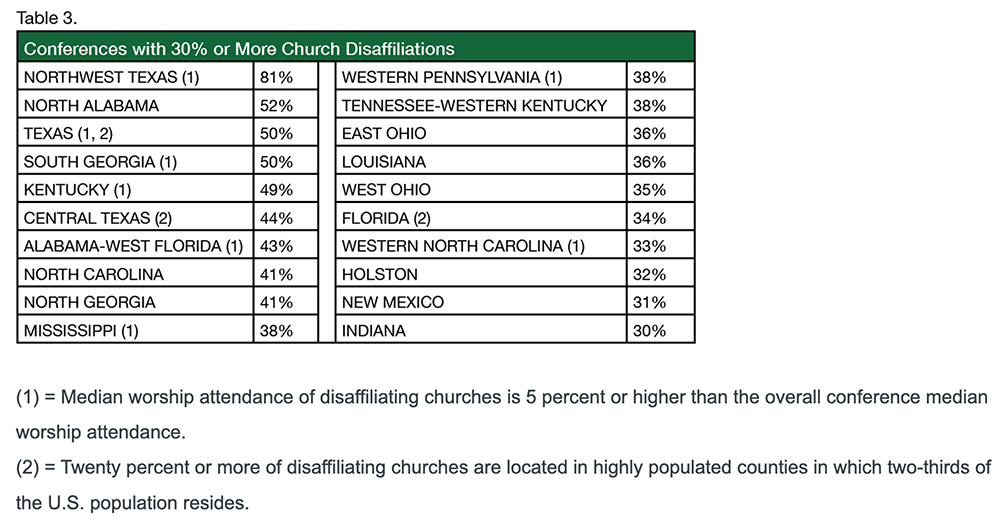

The 10 conferences or church regions with the highest number of departing churches were all in the South and in Texas. In the Northwest Texas Conference, 81% of churches left. The North Alabama Conference came next with 52% of churches leaving the fold.

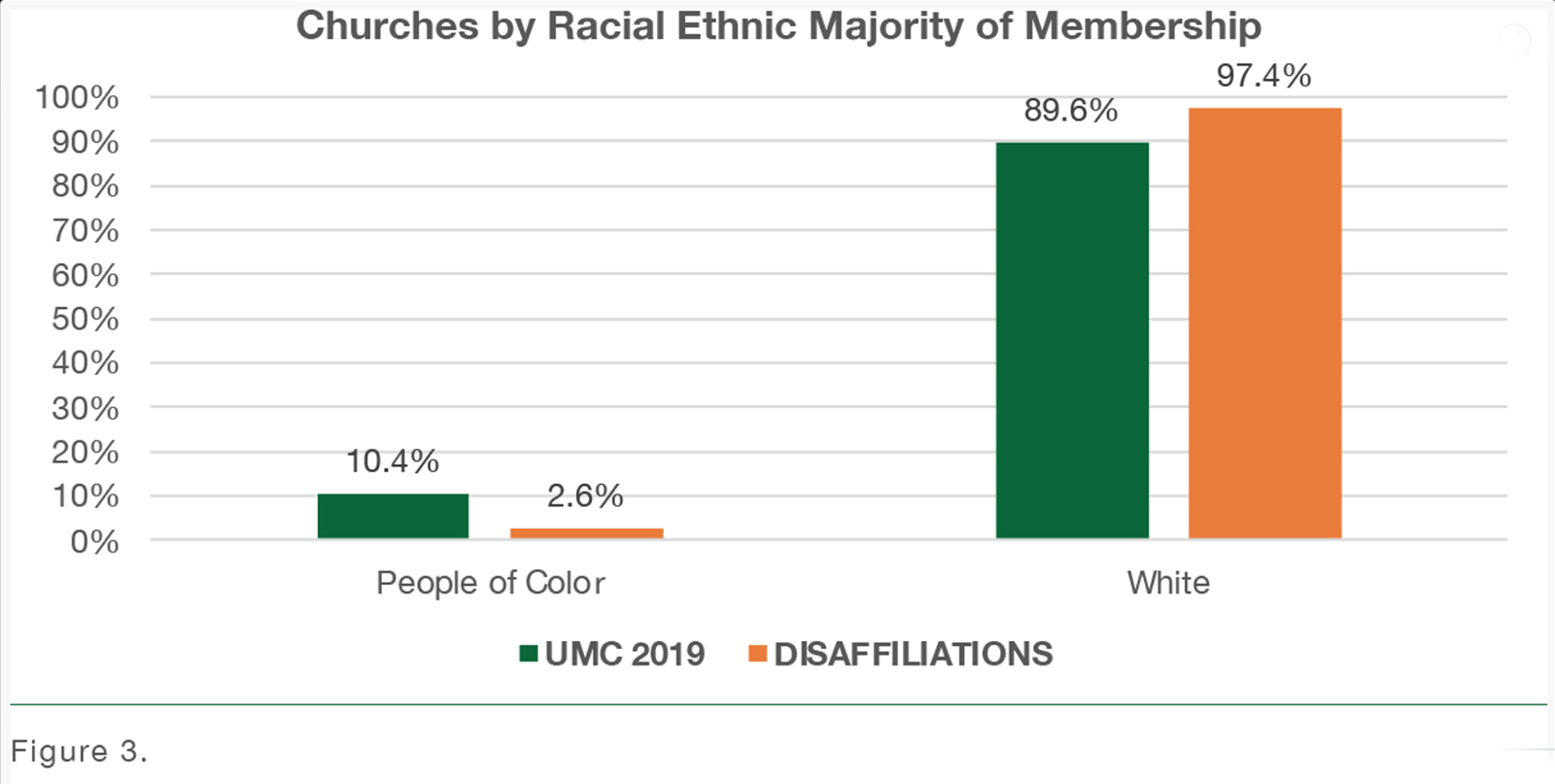

In addition, the study found that race stood out as a factor among the disaffiliating churches. While the United Methodist Church is 89% white, the departing churches were 97% white. Predominantly Black churches — and to a smaller extent, Asian, Hispanic, and Native American churches — were not eager to leave.

Only 1.6% of the denomination’s 7.2% predominantly Black churches left.

“Churches by Racial Ethnic Majority of Membership” (Graphic courtesy Lewis Center for Church Leadership)

Lovett H. Weems Jr., the author of the Lewis Center study and the director of the Lewis Center, put it bluntly: “These churches weren’t anxious to join a secession movement led by white Southern men. That didn’t appeal.”

Departing churches tended to be led by male pastors. Only 19% of disaffiliating churches had a woman as lead pastor at the time of disaffiliation, compared to 29% of United Methodist congregations as a whole that had a woman leader.

The five-year policy allowing churches to disaffiliate expired in December. With the wave of departures now over, the denomination is studying how to right the ship.

The study noted that overall, the 25% disaffiliation rate is considerably higher than that experienced by other mainline denominations that opened the door to LGBTQ marriage and ordination. In the Episcopal Church, the Presbyterian Church USA and the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, less than 10% of churches decamped to more conservative denominations.

“Conferences with 30% or More Church Disaffiliations” (Graphic courtesy Lewis Center for Church Leadership)

A more apt comparison may be with the denominational splits over slavery back in the 19th century, the report concluded. When Methodists split between pro-slavery and abolitionists in 1844, the then-Methodist Episcopal Church lost 40% of its members; they formed the Methodist Episcopal Church, South.

The United Methodist’s legislative arm, the General Conference, will meet in Charlotte, North Carolina, in April to chart a new way forward.

The conference will once again try to sort out how to handle LGBTQ ordinations and marriage, as it has since 1972 when language first was added to the denomination’s Book of Discipline, saying, “the practice of homosexuality is incompatible with Christian teaching.”

In light of broad disagreements over sexuality, the denomination will consider a plan to give its overseas conferences a chance to reject or alter decisions of the General Conference to fit their particular traditions. That would free African and Asian United Methodists, who tend to be more theologically conservative, to keep restrictive policies on LGBTQ people.

The denomination is also working to draft a budget that is 25% smaller and to realign some of its geographic regions or conferences. Three of the six Texas conferences are already working on a consolidation. Another consolidation of conferences is being considered in regions of Alabama and Georgia, where departures were greatest. The Southeast Jurisdiction has already announced it will not elect any new bishops in 2024. The East Ohio and West Ohio conferences will now share a bishop, as will Northern Illinois and Wisconsin conferences.

“We’ve got to find our way back to fulfilling our mission, which is to make disciples of Jesus Christ for the transformation of the world,” said Bickerton. “I’m hoping that in this General Conference session we will be able to devote significant time to that pursuit of finding our sense of purpose again and living out of that purpose with a sense of joy and conviction.”