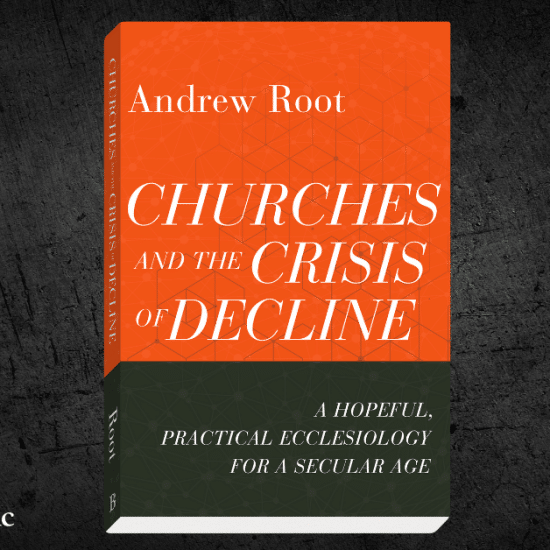

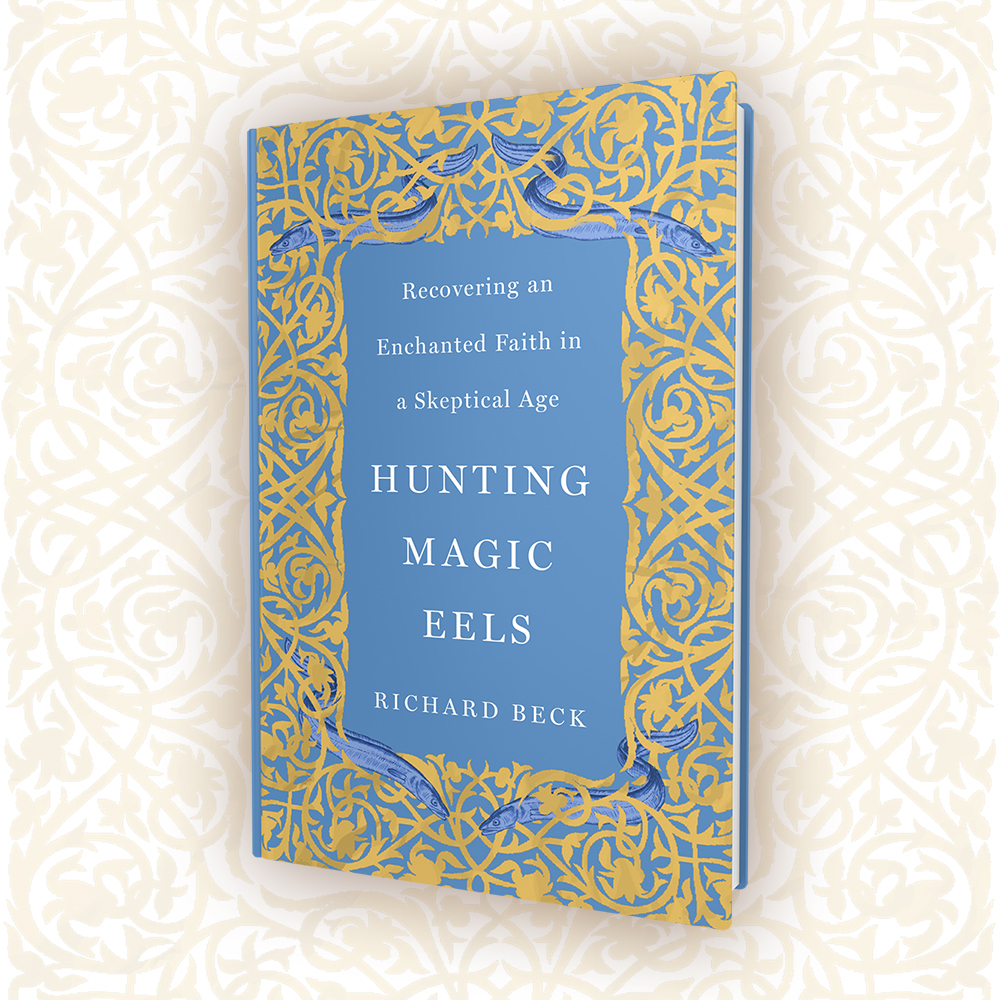

HUNTING MAGIC EELS: Recovering an Enchanted Faith in a Skeptical Age. Paperback Edition. By Richard Beck. Minneapolis, MN: Broadleaf Books, 2024. Xvi + 301 pages.

It is said that we live in an increasingly secular world. It is, we’ve come to believe, a rather disenchanted world. There is much truth to this observation. We live in a very different world from our ancestors whose world was quite enchanted, with angels and demons responsible for all manner of things. The Enlightenment of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and perhaps even the Reformation of the sixteenth century set in motion a process of questioning that enchantedness of an earlier world. Today, it is believed that science has set aside the old superstitions that came with the enchanted world. Oddly, there are signs that many in our modern age hold on to or seek that enchantedness. Thus, even as institutional religion is on the decline in North America and Europe, that doesn’t mean people have lost interest in spiritual things. Consider that many in our world show interest in astrology and other forms of New Age spirituality. Many embrace yoga and meditation as contributors to their spirituality. There is even an increased belief in the presence of ghosts. So, perhaps the world isn’t as disenchanted as we think, even if it is accompanied by growing skepticism of religion that has largely defined the modern world influenced by the rationalism of the Enlightenment. So why does this desire to experience an enchanted world persist?

Robert D. Cornwall

To help answer this question we might want to turn to Richard Beck. Beck is a Christian psychologist and professor who teaches at Abilene Christian University. He comes at this question from an interesting vantage point. First, he is trained as a scientist who asks scientific questions about our world. Secondly, he hails from a Christian tradition, the Churches of Christ, that has been strongly influenced by the Enlightenment (I am a member of a different branch of the same Stone-Campbell Movement, so I understand his background fairly well). With this foundation in psychology and a rationalist religious tradition as a starting point, Beck has pondered this question of enchantedness in several books. Besides Hunting Magic Eels, the book under consideration in this review, he also wrote the very intriguing book titled Reviving Old Scratch: Demons and the Devil for Doubters and the Disenchanted. While the books are different, in many ways Beck covers similar territory in Hunting Magic Eels. The edition under review is an expanded and revised paperback edition that replaces the hardback edition of 2021. Since I didn’t read the first edition (I’m not sure why this is true), I came to this edition, which includes four additional chapters, with a fresh perspective.

As I noted above, like Beck I come from a tradition that is rationalist at its core—the Stone-Campbell Movement. The founders of the movement, especially Alexand Campbell, embraced a modernist/rationalist perspective that has led to a largely disenchanted faith. While influenced by this foundation, in Hunting Magic Eels, Beck invites us to recover an enchanted faith. He uses this intriguing image of magic eels as part of the invitation. You might wonder, what is a magic eel? Beck informs us that back in medieval Wales, there was a well that was said to have been inhabited by magic eels that could predict one’s romantic future. That well would eventually fall into disuse and disrepair, and people stopped seeking assistance from the magic eels in their romantic endeavors, as they pursued a more rational, non-enchanted method.

Over the past several centuries our world has become more scientific, secular, and skeptical. We are often uncomfortable with supernaturalism. Many have made the rejection of supernaturalism a hallmark of their religious life. But is this wise? That is the question Beck raises in Hunting Magic Eels. As Beck writes, “The rising tide of disenchantment has profoundly affected our religious imaginations. We’ve lost our capacity for enchantment, our ability to see and experience God as a living, vital presence in our lives” (p. 3). So, when it comes to being a Christian, we have embraced the idea that religion is intended to make us a good person. This is true of both conservatives and progressives, though what a good person looks like might differ from one pole to the other. While there is truth here, it seems that something more is required. Beck identifies the basic concern as being an ache that we as humanity are experiencing. People are abandoning religion because the moralism they experience in our institutions isn’t enough to heal the pain. With that in mind, Beck invites us to join him on “a journey to reenchant our faith in a skeptical age.” (p. 15).

Beck’s Hunting Magic Eels is divided into four parts, with Part One addressing what he calls “Attention Blindness” in three chapters. Chapter 1 speaks of the “Slow Death of God,” which is the process of disenchantment that has taken place over the last five hundred years (I wonder if this is an aspect of Phyllis Tickle’s grand rummage sale that takes place every half-millennium?). After acknowledging how the process of disenchantment has transpired, he moves in Chapter 2 to address that “ache” that humanity is experiencing. Beck identifies the ache as involving the “death of God” that has transpired over the last few centuries. This ache is revealed through the presence of anxiety, depression, addiction, and other maladies. It is, he suggests, our “disenchantment with disenchantment, the unease and pain we feel without God in our lives” that drives this ache and ultimately makes us sick (pp. 43-44). He identifies this ache as being “our thirst for enchantment and our longing for God” (p. 61). The third chapter in this section speaks of “why good people need God.” That is because there is a need for something deeper that heals the ache and empowers our lives. He speaks to the social justice warriors among us, including many of his students, who he believes need God because “life is morally complicated.” He takes note of Michelle Alexander, who points out in her book The New Jim Crow that “the moral worldview of the social justice movement without God is too narrow, impoverished, and simplistic to deal with the moral complexity of the world” (p. 77). Thus, we need enchantment to engage in this work in a morally complex world. When we look out at the world, with all its challenges, we need more than the proverbial hammer, we need, he believes, a spiritual revolution as well as “a place to go where people love and care for us. Such a place exists, right where you live. Give it a chance” (p. 80).

While Part One lays out the problem of our age, in Part Two, titled “Enchanted Faith,” Beck invites us to consider what an enchanted faith might look like. If, as he believes, we need to reclaim an enchanted faith, what does that involve? He begins this discussion with a chapter focusing on “Eccentric Experiences,” that is, mystical experiences. In laying out his understanding of mystical experiences, Beck draws on William James’ description of a religious experience as “‘a sense of reality, a feeling of objective presence, a perception of what we might call “something there,” more deep and more general’ than what our regular senses reveal to us” (p. 85). After describing the nature of mystical experiences, Beck goes on to discuss living in a one-story universe where God and humans live on the same floor. As Beck suggests, “We’re roommates with God and expect to see each other all the time” (p. 104). Here speaks of, for example, sacraments, which in a one-story universe are more than symbols, where “sacraments participate in and embody the spiritual reality they symbolize” (p. 106). In Chapter 6, titled “The Good Catastrophe” Beck turns to Tolkien for inspiration who describes fairy tales as not make-believe, but “practices of seeing and attention, training ourselves in attitudes of perception” (p. 110). It is an awareness of events that create identity. embrace a good catastrophe, and live beautiful lives. Chapter 7 brings Part Two to a close with a reflection titled “Live Your Beautiful Life.” In this chapter, Beck suggests we live in a “hope-sick” world where hope is difficult to come by. In this chapter, Beck speaks of the path to living a flourishing life. This chapter is wrapped up in eschatological discussions, focusing on teleology. He writes that “without teleology—without story, purpose, and worth—life becomes disenchanted, and we succumb either to despair or tan the anesthetizing powers of consumer culture.” He offers as a response resurrection, where every moment is sacred (p. 154).

When we turn to Part Three, the focus is on not just enchanted faith, but “Enchanted Christianities.” In this section of the book, Beck explores five ways to live into “Enchanted Christianities.” These include Liturgical, Contemplative, Charismatic, and Celtic Enchantments. He concludes these discussions, which seem self-revelatory and inviting, with a summative chapter where Beck explores “the primacy of the invisible” (Chapter 12). By the “primacy of the invisible” Beck envisions paying attention to the things we tend not to see, even though they might be right in front of us. The disenchanted world, Beck suggests, is silent. It doesn’t speak. But an enchanted world is not silent. The problem is that we have found ourselves in that silent world that no longer speaks. By reclaiming the largely invisible enchanted world, we regain a sense of relationality with the world that is rooted in our experiences, so that “what was once invisible slowly comes into view. And a silent world begins to speak” (p. 243).

The book moves to a conclusion in Part Four, “Discerning the Spirits.” Since he has been speaking throughout the book about reclaiming enchantment in an increasingly disenchanted world, he wants the reader to know that not every form of enchantment is helpful or good. Thus, we need tools of discernment. Discernment helps us determine what should and should not be reclaimed. This discussion begins in Chapter 13 with a discussion of “Enchantment Shifting.” What he means by this is that perhaps what we’re observing is not disenchantment but enchantment shifting. We’re moving from “religious” enchantments to “spiritual” ones. So, while he invites us into a more mystical Christianity, he wants us to know that there are forms that need to be resisted. In other words, beware of the truly wacky stuff, which he suggests is often “just baptized self-indulgence, a quasi-mystical gloss we use to mask our selfishness and consumerism” (p. 249). In a chapter titled “Hexing the Taliban” (Chapter 14), he describes a movement within a resurgent paganism to not just cast spells on the Taliban but hexing Allah. It is an interesting chapter that I’ll let the reader discover, but again the question is how do we engage with an enchanted world? What is its end result? The final chapter (Chapter 14), titled “God’s Enchantment,” invites us to pay attention to God’s voice speaking to us. Again, he warns us against thinking of enchantment as baptizing everything we think and believe, including our prejudices, such that we end up worshiping ourselves rather than God. The ultimate test of enchantment according to Richard Beck, as he brings Hunting Magic Eels to a close is “sacrificial love,” that is, giving ourselves for others. It is a form of enchantment that is revealed in the cross of Jesus. As an illustration of this form of enchantment, he points us to Martin Luther King’s sense of call that pushed him on even though death was a constant possibility.

To get to this point of seeking to reclaim enchantment in his own life, Beck acknowledges cultivating his skepticism. I think many of us can resonate with that reality. We’ve struggled with our doubts and questions. It’s a natural part of the spiritual journey. However, he notes that over time he began to recognize that his doubts were self-imposed. He had been cultivating skepticism rather than faith. Thus, he began making different choices and began to open up to new possibilities of enchantment. With this new edition of Hunting Magic Eels, Richard Beck invites us to do the same by cultivating sacramental wonder. If you have read Beck before, you will find Hunting Magic Eels to be as enriching as his other books. If you’ve not read him, well this might be a good place to start. Over the years I’ve found his work to be thought-provoking and spiritually edifying. Might this be true for you as well, as Beck offers us an important guidebook for a journey that can be spiritually enlivening, and yet still Christian. For that, we can be grateful.

This review originally appeared on BobCornwall.com.

Robert D. Cornwall is an ordained minister in the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ). Now retired from his ministry at Central Woodward Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) of Troy, Michigan, he serves as Minister-at-Large in Troy. He holds a Ph.D. in Historical Theology from Fuller Theological Seminary and is the author of numerous books including his latest “Second Thoughts about the Second Coming: Understanding the End Times, Our Future, and Christian Hope” coauthored with Ronald J. Allen. His blog Ponderings on a Faith Journey can be found at www.bobcornwall.com.