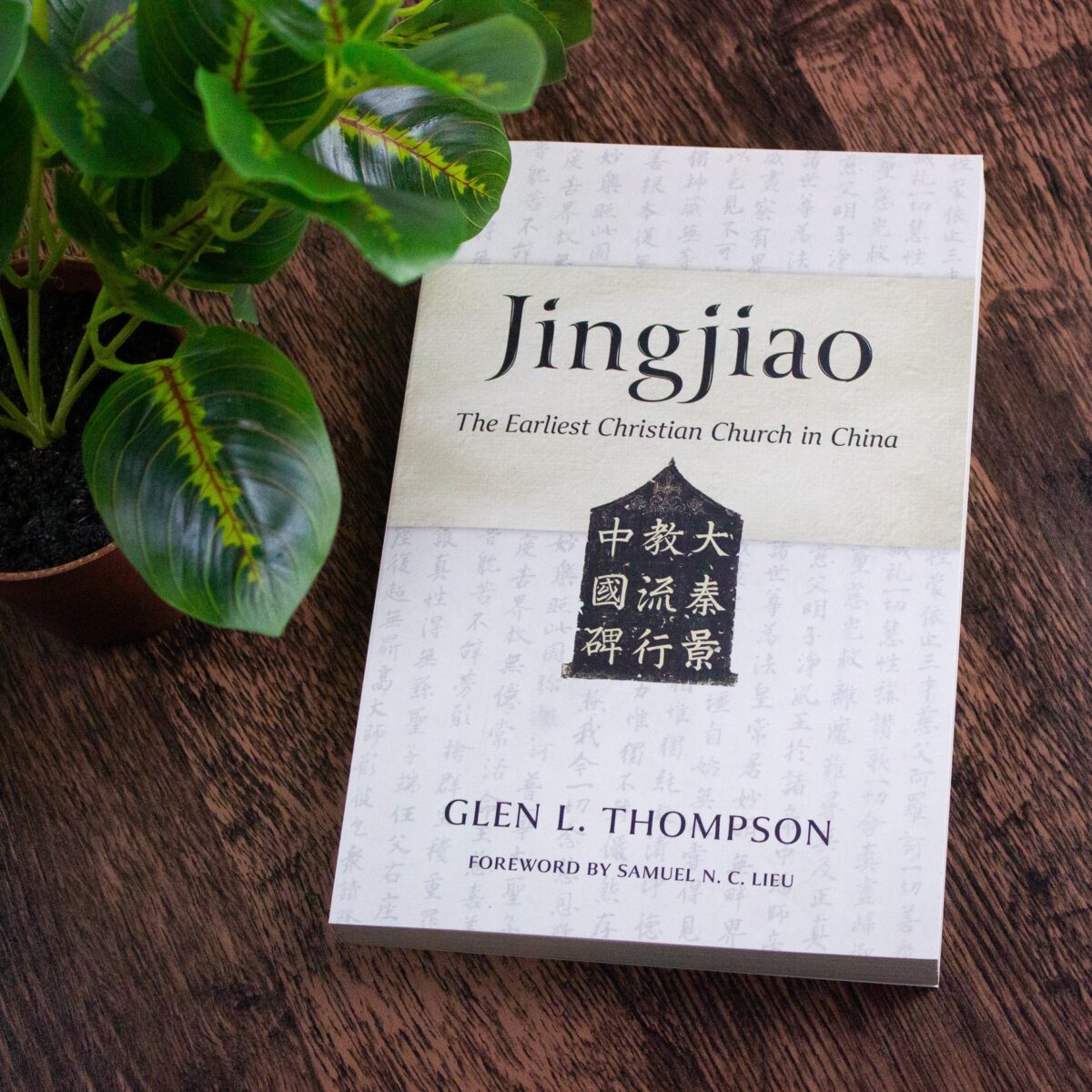

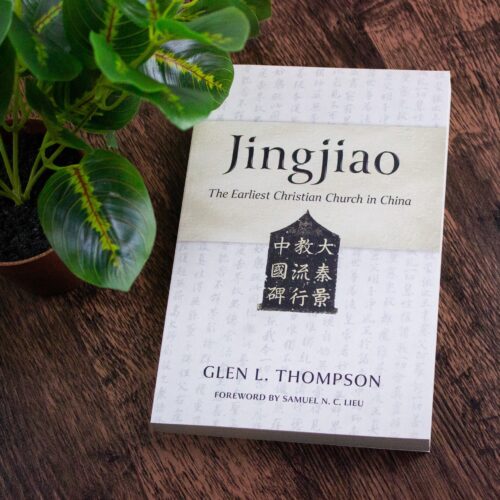

JINGJIAO: The Earliest Christian Church in China. By Glen L. Thompson. Foreword by Samuel N. C. Lieu. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2024x + 269 pages.

Christianity is often defined as being a Western, European religion even if it had its origins in the Middle East. This view of things is largely rooted in the direction that Paul traveled as he spread the message of Christ from Jerusalem to Rome. It’s the story told in the Book of Acts and Paul’s letters and therefore it has canonical support. If we hail from the United States, whether Protestant or Catholic, we likely trace our story back to Europe. While we might recognize Orthodoxy, we think of it in Western terms regarding Russian Orthodox and Greek Orthodox Churches. But for most people, Christianity is a Western religion that spread to other lands due to European colonialism. There is truth to much of this story, but it’s not the full story. There are other stories to be told that can broaden the picture. We know the story of Paul’s missions and we connect Peter with Rome, but what about the other followers of Jesus? What happened to them? What’s their story? What kinds of churches emerged early on from movements east and south?

Robert D. Cornwall

Though much less known in the West there is a long history of Christian presence in lands well to the east and south of Jerusalem, places including India and China. Several Christian traditions emerged in the East, most of which had Syriac origins. These Christian bodies include the Church of the East, which was originally centered in Mesopotamia (modern Iraq) and Persia. The Church of the East, which has its own history and theological developments spread east along the Silk Road. It finally made its way to China early in the seventh century. While modern Christianity in China traces its roots to more recent, largely Western missionary efforts, Christianity has much deeper roots than many of us realize.

Glen Thompson tells the largely unknown story of the earliest Christian churches in China in his book Jingjiao, a Chinese word that roughly translates to “Luminous Teaching.” It is the name given to the earliest Christian community in China. The author of this book that tells the story of Jingjiao, Glen Thompson, is professor emeritus of New Testament and historical theology at Asia Lutheran Seminary in Hong Kong. He now resides in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, where he continues his research on the history of Christianity in China and elsewhere.

Jingjiao is the name given to the Chinese branch of the Church of the East, which was planted in China in the early to mid-seventh century during the Tang Dynasty. The centerpiece of this story is a stele that was created in the ninth century, which tells the story of Chinese Christianity in Chinese characters and Syriac. This stele was discovered in the Tang capital of Chang ‘an (modern Xi’an), located in Western China. The stele was lost for several centuries before being rediscovered in the seventeenth century by Jesuit missionaries. It was then lost again before being discovered in the nineteenth century. This monument tells the story of the planting and development of this branch of the Church of the East in China.

While the word Jingjiao names the earliest Christian community (at least that is known to us), a community that continued to exist for two centuries, Thompson tells the story of two separate periods of Christian presence in China, both of which are connected to the Church of the East.

The first Christian community (Jinbgjiao) in China flourished from its founding in the early seventh century during the Tang Dynasty until it was banned in 845 CE by a later Tang emperor. Before it was banned in the mid-ninth century, this missionary branch of the Church of the East flourished. From what we know from the stele and other documents discovered more recently, this church was welcomed, honored, and respected by the Tang emperors. Imperial politics and crises led to the banning of outside religious communities, largely as a response to the growing presence of Buddhism. A second effort at planting a branch of the Church of the East came during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, which was the period of the Mongol Yuan Dynasty. This church came to be known as the Yelikewenjiao. It flourished under Mongol rule until Timur (also known as Tamerlane) (1336-1405), who envisioned himself as the “Sword of Islam” swept through the Mongol lands and into Mesopotamia and beyond decimating the Christian communities including the Church of the East from China to Mesopotamia (Iraq).

Thompson begins his study by telling the reader that he wanted to get the story of early Chinese Christianity told correctly. He has undertaken this task to make sure that Western Christians get to know this largely unknown story (I taught church history and didn’t spend any time with this movement). He also offers this text to Chinese Christians so they can come to know the larger story of Chinese Christianity, especially since Christianity is often portrayed as a foreign religion with Western origins.

In seeking to tell the story of these two missionary efforts, Thompson begins by telling the story of the Syriac Church and its mission in the East. The primary body is known as the Church of the East. It is the church that likely spread to India and is linked to St. Thomas. While he raises the possibility that Thomas could have gone to China as well as India, we simply do not have sufficient evidence to make such a determination. However, the Church of the East, which is often described as being Nestorian in orientation, spread along the Silk Road, planting churches as it went. As we discover, down through the centuries, the church had its peaks and valleys.

After providing the reader with a brief but helpful introduction to Syriac Christianity and its missionary efforts (it is a valuable chapter because it succinctly discusses Syriac Christianity), we turn in Chapter 2 to “The Stele from Chang ‘an.” This monument mentioned earlier, was created in the eighth century, and then lost to time until its discovery in 1621. It was studied by Jesuit missionary scholars, who determined that this was a monument to a church planted in China centuries before. After again being lost, it gained scholarly attention in the early twentieth century after the stele was moved to a museum in Xi’an. In this chapter, we learn about the monument’s structure and text. We also learn that it was created by a Chinese monk named Jingjing. It is, according to Thompson, “the most complete source of information on the history of the Jingjiao and of its clergy (some seventy are named on the stele) (p. 51).

After he provides us an introduction to the stele and its importance to understanding early Chinese Christianity, in Chapter 3 he goes into greater depth concerning the planting and growth of the church in China during the Tang dynasty. The stele appeared 150 years after the church was planted during the reign of the emperor Taizong (626-649 CE). The missionary who brought the Church of the East to Chang’an was a monk named Alopen who arrived in 635 CE from Persia. We learn that religious activity in the empire was closely monitored, which is a pattern that continues to this day. After the initial planting of the church by Alopen, its viability ebbed and flowed depending on the emperor. While the stele is the original evidence of the church, in Chapter 4 Thompson introduces us to new evidence that was discovered in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, including crosses and tombstones found in northwestern China that add to our knowledge of early Chinese Christianity. In addition, some documents discuss the Chinese church, along with other religious developments, that were found in caves at Dunhuang in Northwestern China. The Christian manuscripts were found there were intermingled with a trove of Buddhist manuscripts. These documents provide more information, especially theological materials, that give evidence of Christian activity, including the theology of these Christians.

After introducing us to the discovery of theologically significant documents in the cave at Dunhuang, Thompson devotes Chapter 5 to a discussion of the teachings of the Jingjiao, setting them in their Chinese context. We see here how the church, rooted in the Syriac Church of the East sought to present the “Christian message in a culturally meaningful way for their Chinese hearers.” (p. 133) To do this effectively, these early Chinese Christians at times borrowed terminology common among Daoist and Buddhist teachers. While there is still much to learn about the theology and beliefs of this church, there is evidence that they tried to enculturate the faith so that it became more indigenous and not simply a foreign religion.

If Chapter 5 introduces us to texts that offer us a look at the theology of these churches, in Chapter 6 we learn more about the Jingjiao as an institution. We learn that the church as it existed under the Tang dynasty, including its organizational structures, followed patterns present elsewhere in the Church of the East. We learn that most of the higher-ranking officials including metropolitans and bishops were sent to China from Persia and Mesopotamia. Thompson also explores how foreign the church remained, especially because the Zoroastrian and Manichaean communities present in the Chinese kingdom did not reach beyond their own communities residing within China. This was not true of the Jingjiao, which sought to bring Chinese converts into the church. When it came to the demise of this church, Thompson notes that it does not appear that their demise came as “a result of long-standing animosities and persecution. Rather, it seems that the Christian church was merely caught up in the imperial crossfire directed against the Buddhists and, to a lesser extent, against the Manichaeans and Zoroastrians. Unfortunately, we have no details about the church during those fateful years” (p. 159).

Chapter 7 picks up the story after the decline and disappearance of the Jingjiao. As noted, the church in China got caught up in an imperial effort to curb the growth of Buddhism in 845 CE. It reemerged or was newly planted several centuries later among the Mongols, among whom the Church of the East had planted. Thus, after the Mongol conquest of China, we see the reemergence of a branch of the Church of the East, which is known as the Yelikewenjiao revival during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. This took place during the Yuan dynasty established by Kublai Khan. It was this church that Western travelers, including Marco Polo, encountered and gave birth to the legends of the church of Prester John. This church grew and then experienced decline as the Mongol rule in China declined. It disappeared once again at the beginning of the Ming dynasty that closed off China to outside influences, including Christianity, which was viewed as a foreign religion. This was also the period when the Persian heartland of the Church of the East was under great stress, which limited its missionary activity and ability to sustain communities such as the one in China.

Thompson titles his Epilogue “So What?” He ponders the question of why this story of these two eras of Christian presence in China before the advent of Western missionary activity in China during the seventeenth century is important. One answer he offers has to do with the importance of dispelling doubts that this church existed. He is able to demonstrate that while this church was never more than a small minority community, its members could be found at the highest levels of Chinese society, including the government. Thus, it bore significant fruit despite its size. Thompson also seeks to dispel the idea that these churches were unorthodox and syncretistic. While they may have used Daoist and Buddhist terminology to produce their theological work and communicate their faith, there is no evidence that they ever strayed from the basic teachings found in the Church of the East, with which the Chinese churches remained in contact and from which they received leadership. In other words, while this church sought to enculturate itself in Chinese life it remained true to its origins in the Church of the East. Therefore, these two small but vibrant Christian communities with Syriac origins existed and flourished long before the Western missionaries arrived, whether Catholic or Protestant. Thus, Christianity has deep roots within China that are anything but Western in orientation.

Glen Thompson’s Jingjiao offers us history and archaeology, along with more background to the nature of Christian missionary efforts. As such he reminds us that Christianity is not merely a Western European and North American religion. We’re reminded of the great diversity of Christian communities, as well as their attempts to enculturate themselves so they can reach members of the communities where they were planted. While much of the story will be new to many readers, even readers who like me are trained in Church History and know some of the story, have much to learn from reading Thompson’s book. So, we can be grateful to Glen Thompson for sharing the story of Jingjiao in an accessible manner.

This review originally appeared on BobCornwall.com.

Robert D. Cornwall is an ordained minister in the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ). Now retired from his ministry at Central Woodward Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) of Troy, Michigan, he serves as Minister-at-Large in Troy. He holds a Ph.D. in Historical Theology from Fuller Theological Seminary and is the author of numerous books including his latest “Second Thoughts about the Second Coming: Understanding the End Times, Our Future, and Christian Hope” coauthored with Ronald J. Allen. His blog Ponderings on a Faith Journey can be found at www.bobcornwall.com.