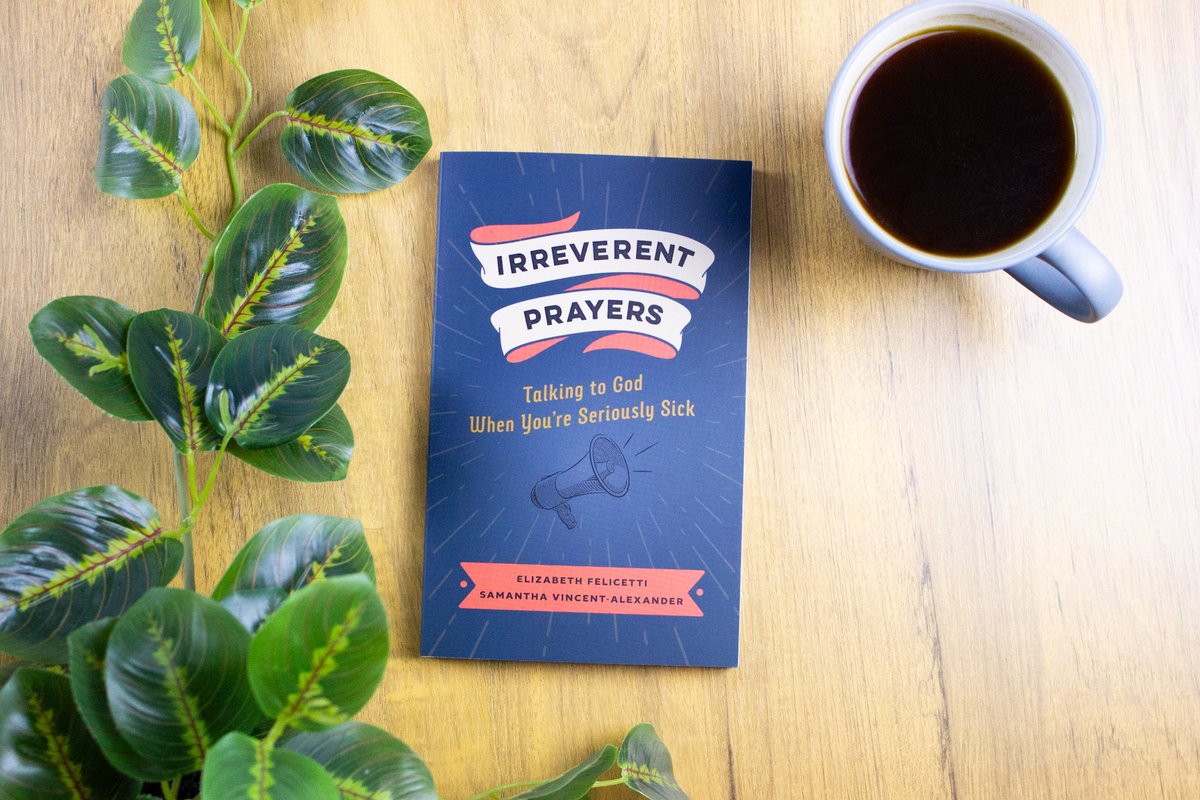

IRREVERENT PRAYERS: Talking to God When You’re Seriously Sick. By Elizabeth Felicetti and Samantha Vincent-Alexander. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2024. Xii + 161 pages.

Prayers are supposed to be reverent, at least that’s what many of us have been taught. When we approach God in prayer, we’re supposed to be respectful and deferential. After all, God is the Creator and we’re not. However, there are times when reverent and deferential prayers don’t reflect the feeling of the moment. Perhaps we feel angry at God or maybe we feel a sense of abandonment because life isn’t going the way we hoped or expected. So how do we let God know that we’re not happy with our situation in life, especially when we’re seriously sick? While the Psalms do give voice to human experiences of illness, injury, loss, and even death, might there be other resources rooted in the Christian faith that provide words that give voice to our existential realities, especially when the typical prayer book doesn’t provide what is needed? If you’ve been looking for a resource that can give voice to your concerns in life, I have good news for you. Two Episcopal priests have created a resource that has emerged out of their own experiences with serious illness, including cancer and serious infections that just might address the needs of those looking for prayers that are reflective of difficult circumstances.

Robert D. Cornwall

The authors of Irreverent Prayers: Talking to God When You’re Seriously Sick are Elizabeth Felicetti and Samantha Vincent-Alexander. Both are Episcopal priests and friends who have experienced serious illnesses. Elizabeth Felicetti is the rector of St. David’s Episcopal Church in Richmond, Virginia. She is also the author of Unexpected Abundance: The Fruitful Lives of Women without Children, a book about women who do not have children for various reasons, which I have reviewed. Her coauthor, Samantha Vincent-Alexander, is the rector of Christ Episcopal Church in Philadelphia. She is the co-author of the book Grace in the Rearview Mirror with three others.

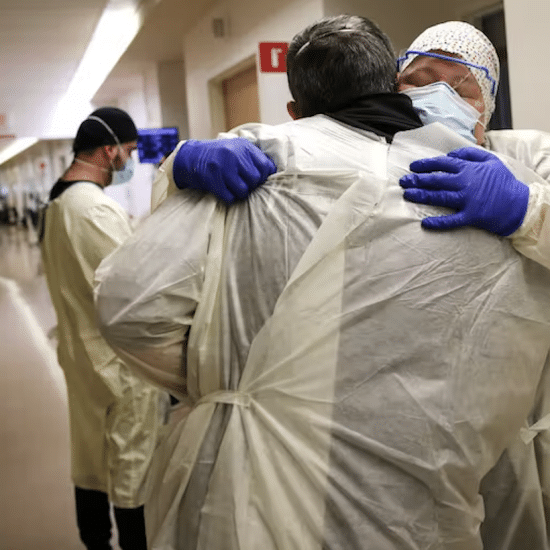

Irreverent Prayers emerged from their own experiences with serious illness. Felicetti has dealt with breast and lung cancer, including a recurrence of the lung cancer. She has experienced significant hospitalization, surgery, and more, all of which tested her faith and ability to pray. Vincent-Alexander experienced MRSA, a serious form of staph infection, which required significant surgery and hospitalization. Both write that they found prayer to be elusive during their illnesses, despite being clergy. This is a good reminder that clergy can struggle with prayer! Being Episcopalians, they turned to the Book of Common Prayer, a book they used regularly in their ministries. However, these prayers did not seem to reflect their experiences. So, they decided to create prayers that would speak to the kinds of feelings they experienced, believing that they might help others connect to God during their health struggles.

Felicetti and Vincent-Alexander introduce Irreverent Prayers by giving an account of their illnesses. Each author takes a turn telling us with some detail what they experienced, one with cancer and the other with MRSA. They tell us about their struggles and desire to find healing and comfort while needing something other than the prayers they had encountered. When it comes to struggling with prayer, Vincent-Alexander wrote: “The prayers of others carried me while I was in the hospital. I couldn’t pray, but I knew others were. I just hoped they weren’t praying for patience. I had far too much practice with that” (p. 20). With that introduction, the authors offer readers seven sets of prayers that reflect different aspects of their experiences. Each chapter is introduced by one of the authors who uses her own experience as a foundation for the prayers they’ve created.

The first chapter/set of prayers is titled “Pain and Anger.” They note that as priests they turned to the Book of Common Prayer during their illnesses, having carried it with them visiting parishioners in the hospital or hospice. Unfortunately, they found the prayers to be hollow when used for themselves. Not only did they find the words of these prayers hollow, but they discovered that many of their parishioners felt guilt about expressing anger to God. While they had recommended the psalms, such as Psalm 22, to parishioners, this didn’t seem to help. In part that has to do with the fact that many of the psalms of lamentation aren’t used regularly in Sunday worship and therefore are not well known to congregants. These discoveries led them to create prayers that reflected these realities. They begin with a variation of Psalm 22, the closing lines of which read: “Stay close now, God, because I’m hurt and alone, and nothing helps. Amen” (p. 23). The chapter includes fourteen prayers that speak to experiences of pain and anger. Among the prayers is one for “When You Can’t Pray.”

Dear God, I can’t. I can’t pray. I can’t bear another moment of this agony. Make me numb to the pain because these narcotics aren’t doing it. I can’t pray because I can’t form words. Paul writes that the Spirit intercedes with sighs too deep for words. Holy Spirit, intercede with those holy sighs. I can only weep at my weakness. Bless my tears. May they be a balm. If you can’t free me from pain, let these tears free me from pain. Amen (p. 25).

The second set of prayers (Chapter 2) is introduced by Samantha Vincent-Alexander and is titled “Blood and Breath.” These prayers draw on biblical symbolism of blood (Vincent-Alexander’s reality) and breath (Felicetti’s). Here we find prayers for wounds, scars, and more. There are prayers for wounds, wound vacs, scars, better veins, chest tubes, and more. Vincent-Alexander writes on behalf of both authors that both blood and breath are important biblical themes. Thus, “we talk about blood in relation to the blood of Christ. When we talk about breath, it’s usually associated with the Holy Spirit. Both are needed to live. When we bleed and when we struggle for breath, we can’t help but feel incredibly vulnerable” (p. 41).

Chapter 3, introduced by Elizabeth Felicetti offers prayers for “Waiting, Wandering, and Wondering.” She reminds us that serious illness can produce boredom, anxiety, and wondering if there is hope for the future. Some of the prayers in this chapter offer responses to calls on the part of friends and family for patience, something that is not easily endured when illness is creating anxiety and concern. Therefore, they offer an “anti-patience prayer.”

Dear God, I am grateful for all the people who are praying for me. Really, I am. But please tell whoever is praying for patience to stop, just stop. I am set with patience. Perhaps they could pray for time to speed up. That would be more helpful. Also, enough with the humility. Tell that prayer warrior to shut up. Amen (p. 61).

Chapter 4, “Hospitals,” is introduced by Vincent-Alexander and offers us prayers for hospitalization. There are prayers here for such things as frustration with being woken up in the middle of the night to be given Tylenol or the constant alarms going off, which no one responds to. There are prayers for doctors and even clean underwear. Some of the prayers are deeply serious and others carry a certain humor, perhaps gallows humor, but still humor. Among the prayers is one for a hospital meal:

Dear God, who told us that we could not live on bread alone, I need you to know that I cannot drink one more ensure. I know it’s good for me and it has all kinds of awesome protein that will help me heal, but it tastes like death. So much tastes like death here. Please share some manna from heaven, but hold the quails. Amen (p. 85).

Everyone who experiences serious illness requiring surgery and hospitalization will have “Well-wishers and Caregivers” (Chapter 5). While both are important, they can at times be a problem. That is especially true of well-wishers. Felicetti writes on behalf of both authors in recognizing that such people mean well, but they want to be authentic in what they write so they can help others deal with their realities. While Felicetti writes that they “offer these prayers with both ambivalence and trepidation as well as love and humor” (p. 101).

Chapter 6, titled “Aftermath,” is introduced by Vincent-Alexander. In this chapter, we encounter prayers that speak to the realities that follow experiences with illness, including recovery, physical therapy, and more. They address the challenges of getting back to some sense of normalcy, which can be difficult. She acknowledges that at points, after a lengthy stay in the hospital, one might desire to return. The first prayer in this chapter speaks to the anxieties and concerns that face a patient being released from the hospital.

Dear God, I have been released from the hospital. I am healed. But I am not. Please release me from the anxiety that comes in the flashbacks and the regrets of what I could have done, should have done, better. Let me feel warm without panicking about a fever. Allow me to see a small cut on someone else’s leg without my mind conjuring images of an infection. Forgive me my wallowing. Release me from memories that come in unexpected times and places and hinder my relationships. I want to be the me I was before the time in the hospital — but I know that will never be. Release me from the expectations. Let me find peace with the wounded person I have become. Amen (p. 123).

The authors title the final chapter of Irreverent Prayers “Relapse” (Chapter 7). This chapter is introduced by Felicetti, who experienced a relapse of her lung cancer, which required the removal of the rest of the cancerous lung. She addresses something she had been taught but which doesn’t seem to work. She had been taught to preach from scars, not wounds, but in her case, the wounds remain. She writes these prayers from the perspective of one who now faces the prospect of an earlier death. When Felicetti asked her doctor if she might live she might live at least five more years, the doctor told her that “the chances were not zero.” It was an honest, if not a reassuring message. Nevertheless, she writes that she hopes she “will live for years and years, and that during that time thousands of people will pray some of the prayers. I hope some will pray these words after I’m gone too” (p. 142). While we don’t know how long she will live, I do believe that many will pray these prayers and find encouragement and solace in the prayers that express anger as well as hope for the future.

As a reviewer of this book, I write as a pastor who has accompanied members through serious illness and death, but I’ve never experienced it for myself. I’ve never personally experienced serious illness or injury. I’ve never even spent a night in a hospital. My wounds may leave scars, but they have been minor. For that I’m grateful. So, I can’t say I’ve personally experienced what Felicetti and Vincent-Alexander the two authors have experienced and described in Irreverent Prayers. But, as I noted, I’ve spent a quarter century serving as a pastor, during which I’ve been called upon to minister to and with people who have experienced serious illness. Members of my family have faced cancer and the need for surgery. Therefore, I understand to a degree the challenges like those described in Irreverent Prayers can impose not only on our bodies but our spiritual lives as well.

While prayer is supposed to sustain us, prayer can be challenging — especially if we believe our prayers should be reverent and not express anger or frustration. We may need prayers that authentically represent what is happening to our bodies and what lies within our hearts. Therefore, we can be thankful for the vulnerability of these two clergywomen, Elizabeth Felicetti and Samantha Vincent-Alexander, who were willing to share their own experiences and create prayers that others can use when irreverence is needed.

This review originally appeared on BobCornwall.com.

Robert D. Cornwall is an ordained minister in the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ). Now retired from his ministry at Central Woodward Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) of Troy, Michigan, he serves as Minister-at-Large in Troy. He holds a Ph.D. in Historical Theology from Fuller Theological Seminary and is the author of numerous books including his latest “Second Thoughts about the Second Coming: Understanding the End Times, Our Future, and Christian Hope” coauthored with Ronald J. Allen. His blog Ponderings on a Faith Journey can be found at www.bobcornwall.com.