(RNS) — If the 1970s were dubbed in Christian circles as “the bookstore revolution,” the first two decades of the 21st century might be more aptly referred to as the bookstore roller-coaster. Thousands of Christian bookstores closed across the country, including mainstay chains like Family Christian. Meanwhile, Christian publishers were acquired by secular giants. And everyone gave up huge profits to Amazon.

The beginnings of Christian publishing in North America are intimately connected to its settler history — the first Bible ever printed in the Colonies was a translation into Massachusett, an Algonquian language, to share it with Indigenous Americans. In subsequent years, evangelism tracts — inexpensive, easily copied, and distributed pamphlets — proliferated.

(Image by 愚木混株 cdd20/Unsplash/Creative Commons)

Today, Christian publishing is an $820 million industry that is in serious flux as the American religious landscape — and the publishing industry writ large — experience massive disruptions. The trajectory of U.S. Christian publishing is complex and defined not only by interconnected trends in religiosity and culture, but by the economy, technology, fads, and, of course, book readership (46% of Americans read no books in 2023 — double the 2022 figure).

What do these trends mean for smaller, denominational presses, and what challenges do they anticipate in the coming years?

The available data regarding sales in the Christian publishing sector is fragmentary. Beth Lewis, the executive director of PCPA (Protestant Church-owned Publishers Association), agreed. “There are global sales data trackers, such as the Association of American Publishers, who regularly publish general data for categories of book sales, such as ‘religion,’” said Lewis. “But they are only capturing data from physical and online bookstores, not direct sales to consumers via a publisher’s website. The numbers of sold Bibles, Sunday school curricula, quarterly subscription devotionals, and music often eclipse book sales. These resources are frequently sold directly by publishers to churches.”

Shrinking churches means the market for Christian print resources diminishes, too.

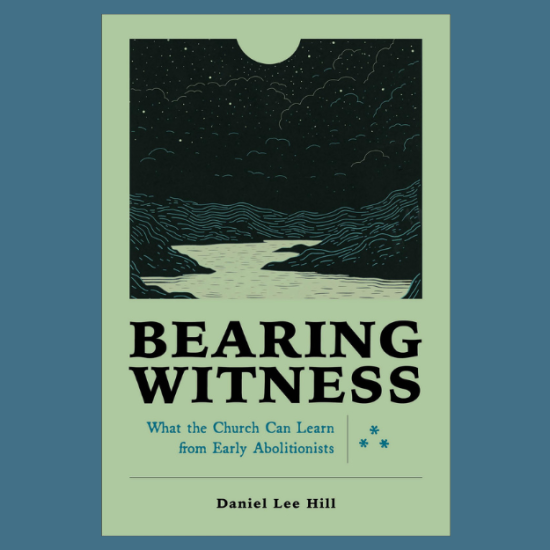

Brad Lyons, president and publisher at Chalice Press, a Disciples of Christ denominational press, appeared very somber about the outlook of mainline Christian publishing. “The industry as a whole is under siege,” he said, citing Amazon’s aggressive sales strategies as well as the decline of mainline Protestantism and the growth of evangelical publishing. During the last five years, there have been bumps in sales, however; anti-racist resources began selling during the racial justice protests after the murder of George Floyd; also, faith resources for young children and families were a big success in 2020. Titles that help Christian readers reckon with current affairs are in demand.

David M. Hetherington, vice president of Books International, a book fulfillment company (printing, storing, packing, shipping books to customers) that serves mainline Protestant, evangelical, Catholic and Jewish publishers, also addressed the question of Amazon’s dominance. “It’s the 800-pound gorilla in the room; it’s a force to be reckoned with,” Hetherington said.

Amazon and other large online sellers “require deep discounts from publishers, eroding publishers’ and authors’ revenue,” explained Lewis.

Jeff Crosby, CEO of the Evangelical Christian Publishers Association, said in an interview that more than 50% of the publishing and sales of Christian books happens “under a single corporate entity” (which was named by the article author as Amazon). This poses an obvious risk to the viability of the industry, as one distribution channel deeply impacts the finances of the industry.

But there’s more. The decline of Christian brick-and-mortar bookstores means it is harder to sell religious books, as secular chain bookstores give them a much smaller “footprint” on the floor. “Selling them is more challenging than it’s ever been,” said Hetherington.

Global affairs also affect book sales, he pointed out, citing “staggering” cost increases for publishers who manufacture in China or India. First, the pandemic caused the costs to skyrocket; then, the most recent unrest in the Middle East and ensuing attacks on commercial vessels mean costs have increased again; shipments must be rerouted around Africa to reach Europe and the United States.

Brian Flagler and Craig Gipson from Flagler Law Group, a legal firm that advises Christian publishers and other Christian entities on contracts and copyrights, also listed distribution and supply chain problems as major challenges for Christian publishing. They also noted the rise of artificial intelligence. At the 2024 annual meeting of PCPA in St. Louis, AI was one of the main themes.

“We’re following the opinions from the U.S. Copyright Office to advise our clients on rights: If you create a book cover using AI platform, can you own the rights? When is it appropriate to use AI to create study guides? And what kind of tasks are we comfortable with AI doing for us to make us more efficient, but without kind of violating any kind of ethical responsibility to readers? New things in the AI field are popping up almost daily that should be considered,” Gipson said.

The diversity of the author base is also a concern, said Lyons. “We’re not where we want to be yet. I think we have probably a larger number of women authors than most Christian publishers, but I would like to have more authors from the Asian and Hispanic communities.”

The answer to some of the challenges that Christian publishing is facing lies in developing new business models, and the most important one, according to Hetherington, is building a strong community with its constituency, especially online. “That way, they can build a community, that they can own that community, that they can cultivate that community, and they are not relegating that community to Amazon.”

This understanding is shared by many publishing houses. Cheryl Price, the publisher at Judson Press, talked about other aspects of community-building she intends to put in place. “We’re going to have a Judson Press book club. We’re going to have writing workshops for aspiring authors, and we’re going to publish writing tips on our new website. We’re also working on building a digital visual library of authors who will share information about themselves and their books.”

Christian publishers understand they need community, too. PCPA members meet regularly to discuss strategies and solutions to problems they all face. Lewis said PCPA is an unusual body, because political differences are left at the door. “Leaning more conservative or liberal, all presses need to deal with issues with sales, distribution and marketing,” she said. “PCPA is a place where a publisher can ask a question on the forum, and everyone regardless of their political stance rushes to help. It is pretty unusual given what we are observing in public life today.”

In the United States, we’re polarized religiously and politically, but here’s an example of people who can work across the lines of difference. Perhaps that, too, can signal a path forward for religious communities. Only time will tell if the center holds.

(Anna Piela, an American Baptist Churches USA minister, is a visiting scholar of religious studies and gender at Northwestern University and the author of “Wearing the Niqab: Muslim Women in the UK and the US.” She is also the senior writer at American Baptist Home Mission Societies. The views expressed in this commentary are the author’s alone and do not represent the ABCUSA or the American Baptist Home Mission Societies. Nor do they necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)