Two weeks after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, Republican U.S. Rep. Bill Shuster of Pennsylvania stood in the House chamber to offer words he had heard two days earlier while in church. He shared the words from his pastor, who had reminded the congregation that even in the shadow of terrorism that God is still good, in control, and still God. In addition to talking about the need for the American people to come together as a community, the pastor also preemptively defended military action in response to the attacks.

A conservative politician who later became one of Donald Trump’s earliest congressional endorsers in 2016, it’s not surprising Shuster placed a sermon from his home congregation into the Congressional Record or that the next year Shuster brought another pastor to the House chamber as a guest chaplain to open a session in prayer. But in light of the attacks the past week on Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz’s faith, it might be surprising for Walz’s critics to realize Shuster and other Republicans are part of the same denomination being called “extremely left-wing.”

Like Walz, Shuster’s church is part of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (which despite the word “evangelical” in the group’s name is one of the “seven sisters” of the mainline Protestant world that’s had a lot of political and cultural influence). Since Vice President Kamala Harris picked Walz as her running mate, some conservative websites have attacked the ELCA and Walz’s local church as alleged proof that he’s radical and not truly Christian.

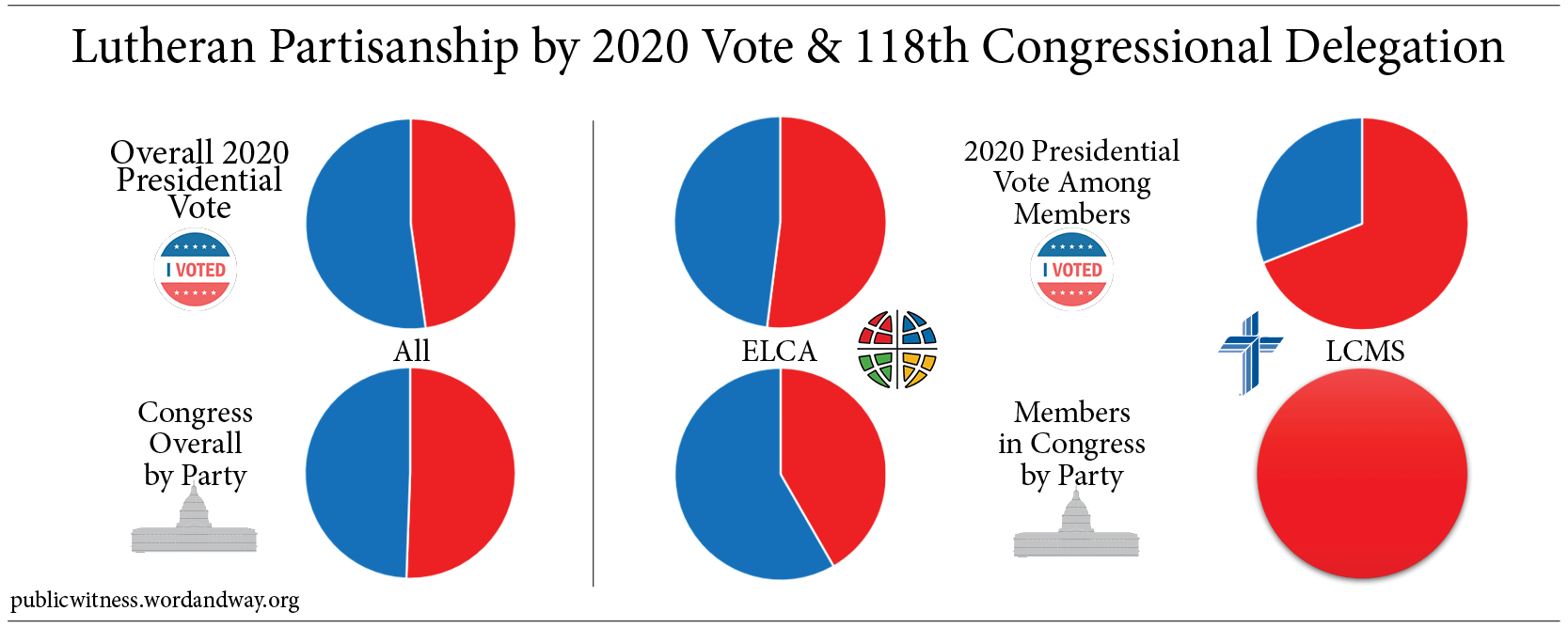

As I noted last week, the ELCA includes political diversity and actually saw a slight majority of its members vote for Trump in 2020. Yet, the attacks from rightwing sites continued. Even Christianity Today got in the action, questioning Walz’s Lutheran identity. To do that, they asked a conservative political activist and two members of the Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod, a smaller, more conservative, and evangelical denomination (which is a bit like judging the Southern Baptist Convention by asking independent, fundamentalist Baptists what they think).

ELCA Presiding Bishop Elizabeth Eaton (far left) addresses the ELCA Churchwide Assembly in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, on Aug. 8, 2019. (Emily McFarlan Miller/Religion News Service)

With Walz’s mere membership in the ELCA lifted up as proof that he’s liberal, it’s worth looking at the political membership of that denomination as well as other Lutheran groups framing themselves as the non-extreme alternatives. One way to do this is by analyzing the membership of Lutherans in Congress, where Walz served for 12 years before moving into the Governor’s Residence. So this issue of A Public Witness tracks which denominations Lutheran congressional members are part of to consider what that reveals about Lutheran life and the broader Christian witness.

Finding Congressional Lutherans

Every two years as a new session of Congress begins, Pew Research Center releases a report analyzing the religious composition of the House and Senate (which is based on self-reporting of religious affiliation from congressional offices to CQ Roll Call). For the 118th Congress, which started in January 2023, Pew noted the general category of “Lutheran” included 22 members. However, the data does not note which Lutheran denomination or if the members actually attend somewhere.

For this analysis, I started with Pew’s list of 22 Lutheran lawmakers. By checking congressional biographies and social media accounts, searching for news reports, and reaching out to congressional offices, I connected most of the members to a congregation.

House members stand with their families as a prayer is read in the House chamber on the opening day of the 118th Congress at the U.S. Capitol, on Jan. 3, 2023. (Alex Brandon/Associated Press)

I removed one member — Republican Sen. Ben Sasse of Nebraska — because he had since left Congress. No new members since January 2023 identify as Lutheran. Of the remaining 21, I was able to find a local congregation or denominational identification for 18 of them. I removed the other three from this analysis. One of them (a Democrat), has specifically stated in an interview that he was raised Lutheran but doesn’t attend, adding that his wife and children are Jewish. It’s possible the other two (both Democrats) aren’t actually attending or connected to a church but still identify as Lutheran when asked by CQ Roll Call.

Additionally, I found two other lawmakers who are part of a Lutheran congregation. These lawmakers were listed in Pew’s data as “Protestant unspecified,” a generic term that’s been growing in use by congressional members in recent years.

Altogether, this gave me a list of 20 lawmakers from 17 states who I could connect to a Lutheran denomination. Of these, there are 13 Republicans and 7 Democrats, with 14 of them serving in the House and another 6 in the Senate.

A Partisan Divide

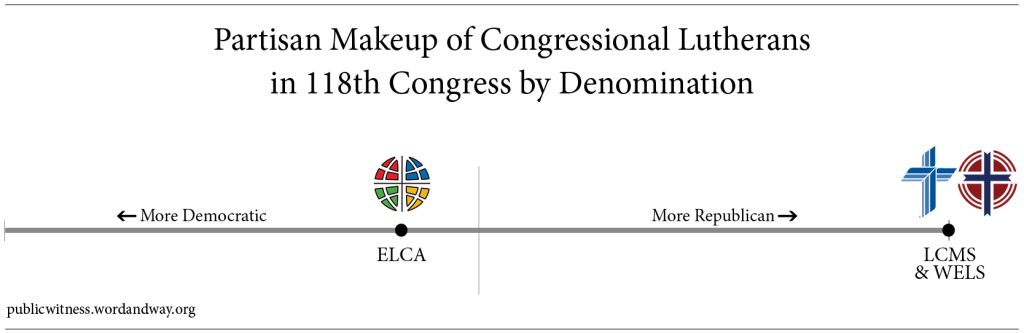

Of the 20 Lutheran members identified, 12 belong to the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America that Walz is part of, while 7 are in the more conservative Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod. One other member, Republican Sen. Ron Johnson of Wisconsin, is part of the Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod, which is smaller and more conservative than the other two bodies. These numbers change can every two years with a new Congress. For instance, the WELS recently also had a Democratic member, Rep. Ron Kind of Wisconsin, serving until he retired after the last term.

Like the WELS with its solitary GOP member, all 7 current LCMS congressional members are Republicans. The ELCA, on the other hand, has partisan diversity. Seven members are Democrats (58%) and 5 are Republicans (42%). The diversity changes a bit per chamber. While 3 of the 4 ELCA senators are Democrats (75%), the House divide for ELCA members if evenly split with 4 members in each party.

As the partisan breakdown demonstrates, not only is the ELCA not extremely liberal in its congressional delegation, it’s also the only Lutheran denomination currently with members in both parties in Congress. Activists in the LCMS attacking Walz’s ELCA as radical are doing so from a denomination that is farther from the political median. That can also be seen in the 2020 presidential election as 52% of ELCA members voted for Trump while 69% of LCMS members did. Far from leftwing, the ELCA was actually one of the most evenly-divided of the 20 largest majority White denominations.

Not only does the vote share of the LCMS membership signal a denomination with less political diversity than in the ELCA, but the congressional delegations demonstrate that even more. Despite the attacks by LCMS members on the ELCA, the ELCA’s congressional delegation is more than 40% Republican. This means some significant conservative figures are in the denomination.

Like Sen. Joni Ernst of Iowa, who has long been part of an ELCA congregation in Stanton. As the fourth-ranking Republican in the Senate, she’s the top Lutheran in Congress. A reliably conservative vote, she called Barack Obama a dictator, voted to acquit Trump in both impeachment trials, argued President Joe Biden should be impeached, praised Trump’s handling of the COVID-19 pandemic, voted against investigating the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol, and urged the Supreme Court to overturn Roe v. Wade. Clearly, being part of the ELCA does not make her a liberal.

Another Republican in an ELCA church is Rep. Dusty Johnson of South Dakota. Although he doesn’t have as rightwing of a reputation as Ernst, he’s still a conservative Republican representing a solidly red state. He’s also been a Sunday School teacher at his local church and traveled on a short-term mission trip to Haiti. Being an active part of an ELCA congregation obviously doesn’t mean he’s inherently leftwing.

Walz may suddenly be the most famous ELCA politician, but the whole denomination shouldn’t be judged through him — just as it would’ve been a mistake to view Southern Baptists in the 1990s only by the politics of their most famous member in public office at the time, President Bill Clinton. Beyond the U.S. Congress, we can also find many ELCA members in both parties in state legislatures and other political offices. That’s especially true in states like Walz’s Minnesota where the group is the largest Protestant denomination.

Get cutting-edge analysis and commentary like this in your inbox every week by subscribing today!

The Difficulty of Purple Denominations

The members of the 118th Congress show which Lutheran denominations in public life have the most partisan leaning. Only the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America has a bipartisan delegation, while the Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod and the Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod currently only send Republicans to Congress. This means ELCA members are more likely to see someone from their faith tradition holding political positions with which they disagree and therefore must learn to remain in communion despite partisan disagreements.

The party affiliations of clergy add to the partisan tilt. Nearly 90% of LCMS clergy and nearly all WELS clergy with party registration are Republicans. Those findings put both denominations among the most lopsidedly partisan Christian bodies in a 2017 study. No majority White denomination has near as high of a percentage of Democratic clergy as those two Lutheran groups have with Republican clergy. The same study also found ELCA pastors lean more Democratic than their members, but Democratic clergy in the ELCA only outnumber Republicans by about three-to-one instead of nine-to-one.

For a denomination where nearly all the clergy and congressional members are in one party and a strong majority of the membership also vote that way, it’s easier for denominational leaders and clergy to engage in partisan politics since they know they won’t face much pushback internally. This could make it easier for churches to fall into partisan groupthink since they will frequently lack political diversity within their sanctuaries. On the other hand, pastors in churches and denominations with political diversity are more likely to consider the perspectives of those on the other side because they are in relationship with them.

What this analysis reveals is not merely the inaccuracy of partisan attacks on Walz’s denomination. More dangerously, it shows the problem of viewing everything through a partisan lens. While some critics of the ELCA — like those in more conservative Lutheran groups — do have significant theological disagreements, the recent swell of attacks are largely made in bad faith. The complaints aren’t about making a theological point but winning an election. Theology is being used as a partisan weapon. Thus, even a denomination with significant Republican politicians is under attack in the name of scoring points in a presidential campaign.

Such attacks could aid the ongoing divide into red and blue churches, and red and blue denominations. How will conservative members of the ELCA react when they see the partisan attacks on their denomination? Will it lead them to stop trusting the rightwing commentators making such arguments? Or will it inspire them to consider switching churches? Sadly, party often trumps faith.

Consider the troubling research finding from Robert Putnam and David Campbell as they looked at what happens when politics and church collide. It used to be that if one’s political party and one’s church came into conflict, one would most likely change one’s politics or even one’s party. Now, the reverse is true as Americans have “adjusted their religion to fit their politics.” As the scholars explained, “We were initially skeptical about that proposition, because it seemed implausible that people would make choices that might affect their eternal fate based on how they felt about George W. Bush. But the evidence convinced us that many Americans now are sorting themselves out on Sunday morning on the basis of their political views.”

The rise of Trump and the debates about COVID-19 public health measures have likely only increased this partisan pew sorting. Attacks on a denomination motivated by a partisan desire to win a presidential election can also add to this sorting. Some denominations — like the LCMS and the WELS — have largely already shifted completely to one party. The few remaining purplish denominations like the ELCA often find themselves under attack from preachers of a partisan gospel.

As a public witness,

Brian Kaylor

A Public Witness is a reader-supported publication of Word&Way.

To receive new posts and support our journalism ministry, subscribe today.