(RNS) — Most American churches navigated the patchwork of COVID-19 restrictions on public gatherings by periodically closing their doors and broadcasting services online instead.

But for almost half of U.S. Orthodox Christians, whose liturgy involves processions, incense, kissing icons and crosses and receiving Communion from a shared spoon and chalice, liturgical services continued for anyone wanting to attend in person, according to a new study of how the denomination weathered the pandemic.

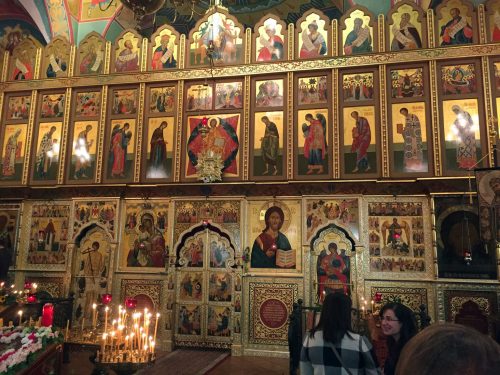

The Cathedral of St. John the Baptist in Washington, D.C. (RNS photo/Mary Gladstone)

The new study finds that Orthodox churches overall were reluctant to embrace virtual worship compared to all religious congregations. By spring 2023, 75% of all U.S. congregations provided remote options compared to only 53% of Orthodox churches.

Fewer online options likely contributed to the significant drop in Orthodox church participation in the middle of the pandemic in 2021, but compared to other U.S. congregations that are on average 8% below pre-COVID-19 attendance, Orthodox churches had recovered in-person attendance on average by spring 2023.

At the same time, Orthodox churches overall have seen a drop in volunteer participation, from 40% in 2020 to 25% in 2023, compared to 40% and 35% in all U.S. congregations.

The Orthodox tendency to “ignore” the pandemic has produced a “mixed bag,” said research released Thursday (Aug. 22) by the Hartford Institute for Religion Research and Alexei Krindatch, national coordinator of the U.S. Census of Orthodox Christian Churches. Orthodox churches in the U.S. are more likely than other religious congregations to have gained members during the COVID-19 pandemic, even while struggling with declines in participation and volunteering.

Using survey data from 2020 through 2023, the study found 44% of Orthodox churches remained open during the pandemic, compared to just 12% of all U.S. congregations. Only 31% of Orthodox priests publicly encouraged parishioners to get vaccinated compared to 62% of all clergy.

“They were trying to avoid conflicts,” said Krindatch, the study’s lead researcher, who has published earlier reports on how the pandemic impacted Orthodox Christians.

“Compared to Other U.S. Religious Congregations, Orthodox Christian Parishes Were More Likely to “Ignore” the Pandemic” (Graphic courtesy HIRR)

There is no single Orthodox Church in the U.S. Instead, several jurisdictions — the largest are the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese, the Orthodox Church in America, and the Antiochian Orthodox Archdiocese — are administered independently of one another and exist side by side, sharing the same teachings and in full communion with one another. Many Orthodox parishes combine several immigrant groups and their descendants, from Russians and Ukrainians to Arabs and Greeks, as well as converts from other faiths and denominations.

Bishops provided pandemic guidance to the priests serving them, such as whether to require masking or not, often across a swath of states that clashed on masking and lockdown mandates. Priests then chose whether and how to follow or adapt that guidance to their specific circumstances, sometimes casting doubt on the bishop’s authority.

“I figured people are going to make their own medical decisions (about the vaccine),” said one Orthodox priest who participated in the survey, the Rev. Lawrence Margitich of St. Seraphim of Sarov Cathedral in Santa Rosa, California, a parish of the Orthodox Church of America. “I’m the priest. What do I know about that stuff?”

Margitich said his church has grown from about 80 people on a Sunday morning in the pre-pandemic months of 2020 to about 180 people today. To reduce the spread of the coronavirus, in 2020, the church moved services to its outdoor courtyard with an amplified sound system. Then in August 2020, smoke from a major wildfire pushed them back inside.

During that double crisis, in which hundreds of local homes burned to the ground, people began showing up to St. Seraphim.

“They started thinking more about eternal realities, I guess, and their life in this world,” said Margitich.

According to several Orthodox clergy who have spoken to RNS, the pandemic lockdowns provided more time at home to browse the Internet and self-reflect, leading many spiritual seekers to come across Orthodoxy for the first time across a proliferation of English-language resources online and then visit a local church.

This year, St. Seraphim of Sarov Cathedral has experienced more baptisms than ever before in Margitich’s 27-year career, he said, with 20 people catechized in the spring and 20 more in the process of conversion.

An earlier report by Krindatch concluded that while most Orthodox churches in the U.S. shrank an average of 15% in regular attendees from 2020 to 2022, 1 in 5 parishes instead grew their membership and in-person attendance by 20%. The growing parishes tend to be those that not only remained open for in-person worship during the pandemic but also didn’t offer online worship, have a higher percentage of converts, and have greater unity of opinions, among other factors.

By spring 2023, 15% of the members of a median Orthodox parish were newcomers who had joined since the start of the pandemic in 2020, compared to only 10% among other U.S. religious congregations, the latest study showed.

“It is a statistically significant difference,” Krindatch said. “But there are bigger differences between Orthodox jurisdictions. People were definitely looking for any place they could join.”

The Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia, commonly called ROCOR and considered the most conservative jurisdiction, picked up significantly more members than the Orthodox Church of America, which in turn picked up more than the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese, according to Krindatch’s data.

The Rev. Luke Veronis of Sts. Constantine and Helen Greek Orthodox Church in Webster, Massachusetts, near the Connecticut border, called the pandemic a “positive” experience for his parish, despite describing his congregation as “extremely divided” politically, with both progressives and Donald Trump loyalists, who he refers to as “a family.” The COVID-19 restrictions pushed the church to livestream services and meet on Zoom, alternatives they have continued to offer for liturgies and Bible studies alongside the in-person gatherings.

Veronis’ church also experienced atypical growth, from 150 regular monthly attendees in 2019 to about 220 today, he said. Most joined during the pandemic and are young adults under the age of 35. Many of the Greek Orthodox churches in New England are either declining or struggling to remain open, while only a handful are growing.

“The key to our success is we’ve created a very welcoming church,” said Veronis, who also teaches a class about cultivating “missions-minded” parishes at Hellenic College and Holy Cross Orthodox School of Theology in Brookline, Massachusetts. “I always preach to my people, our church welcomes everybody … but then, of course, the challenge for everybody is once you come into the church, we all are on a journey of change and transformation. So don’t come with your agendas.”

He calls the surge in membership some churches are experiencing “both a blessing and a curse.”

“One of the real challenges we in the Orthodox Church are going to have is we have a lot of people coming into our church now, especially young men,” he said. While expressing gratitude for the men who have found his parish, he added, “I would be afraid if some of these men went to some other Orthodox churches, where the priests themselves have given in to these ideological wars and these priests would just feed into what these men are already looking for, the right-wing, extreme craziness.”

The study is part of a national mixed-methods project titled Exploring the Pandemic Impact on Congregations and funded by the Lily Endowment that is investigating changes to congregational life resulting from COVID-19. Faith Communities Today provided 2020 survey data of over 15,000 congregations on the pre-pandemic congregational landscape.

The next survey in November 2024 will follow up on many of the same themes to examine how the pandemic’s impacts continue to change how congregations operate and collect perspectives from not just clergy but also lay persons.