WASHINGTON (RNS) — “Lift Every Voice and Sing” is a hymn many African Americans of older generations just know.

They’d sung it in church, learned it in school, and stood for what is dubbed the unofficial Black national anthem just like they might for “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

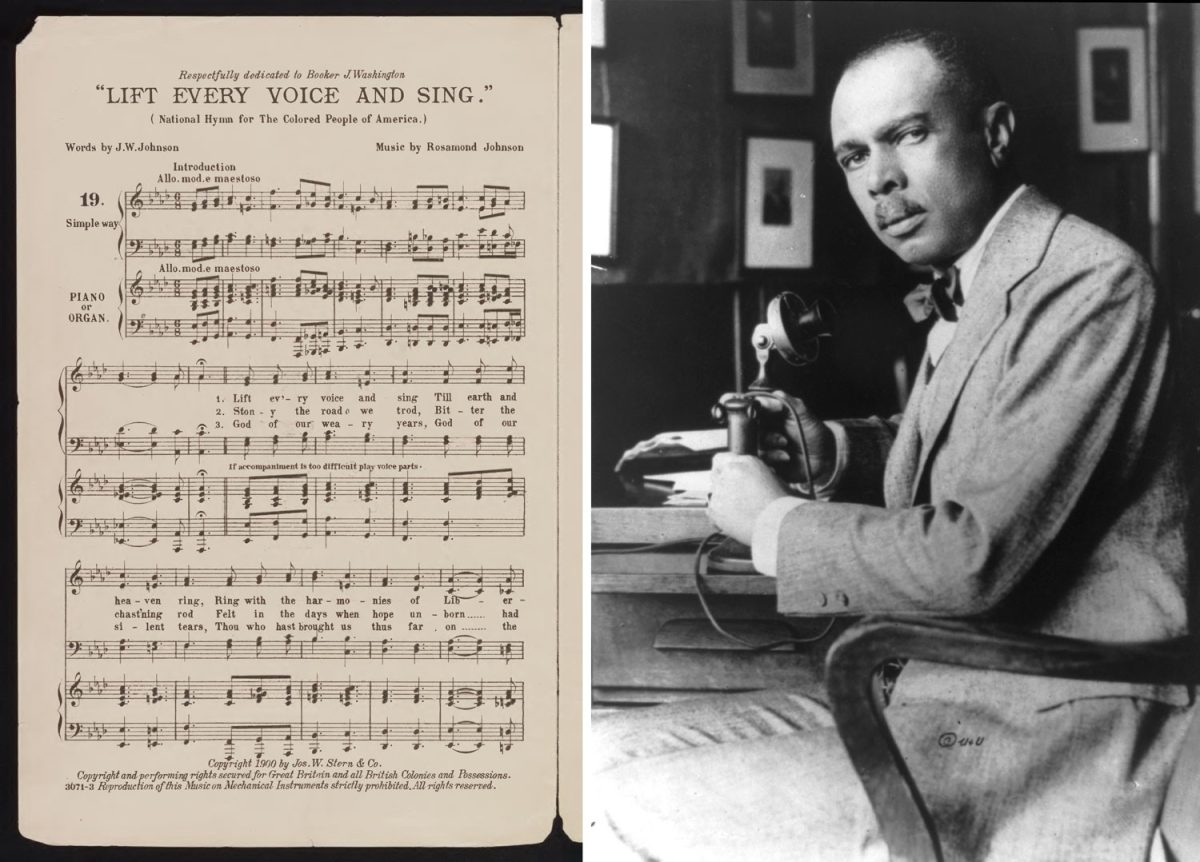

First page of music for “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” written by James Weldon Johnson. Images courtesy Library of Congress

“Lift every voice and sing/’Til earth and heaven ring/Ring with the harmonies of Liberty,” it begins. “Let our rejoicing rise/High as the list’ning skies/Let it resound loud as the rolling sea.”

Courtney-Savali Andrews, an assistant professor at Oberlin College’s Conservatory of Music in Northeast Ohio, was born in the mid-1970s in Seattle, where the song — which turns 125 years old this year — was a staple at her Baptist church and in the wider Black community.

“It was impressed upon me, particularly from the ministers of music and the pastor, that not only did I have to sing the song with a full-heartedness, I also had to memorize all of the words,” she recalled in mid-June at the Museum of the Bible in Washington, D.C. “And so, it was one of those items that you did not want to be caught, specifically by your peers, looking into the hymnal.”

Andrews, who studies African American and African diasporic music, was one of a dozen speakers at a daylong symposium on “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” on Thursday (June 12) at the museum.

The song was first publicly sung by a group of 500 Black schoolchildren in 1900 in Jacksonville, Florida, to commemorate the birthday of President Abraham Lincoln. Its words were written by educator and civil rights activist James Weldon Johnson for the occasion, and his brother, J. Rosamond Johnson, set them to music.

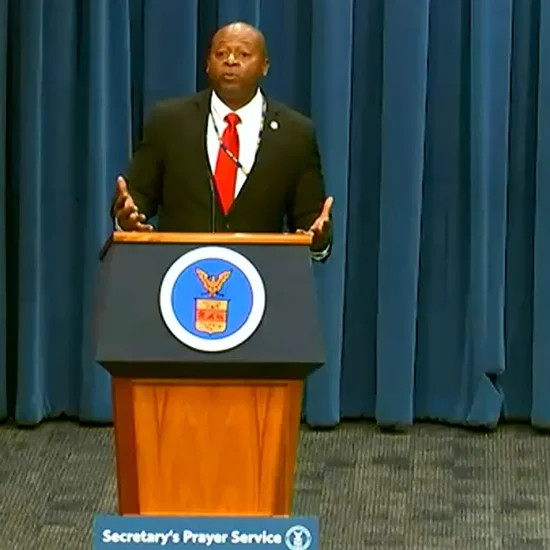

“They both saw artistic and cultural excellence as a major key to Black advancement in America,” said Theodore Thorpe III, a Virginia church musician and high school choral director, and the symposium’s keynote speaker. “The hymn continued to resonate and reverberate, even beyond the expectations of the Johnson brothers.”

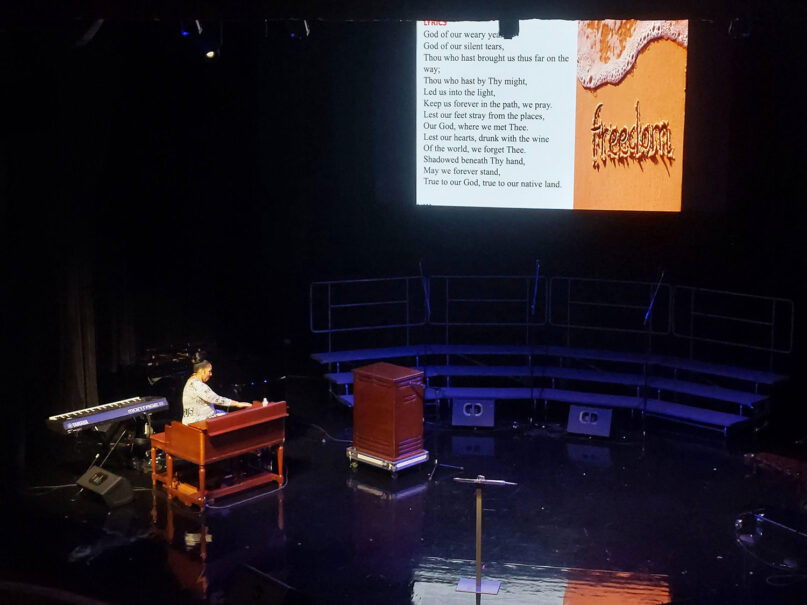

Pastor Ovella Davis of Always in Jesus’ Presence Ministries in Detroit presented a workshop on the Hammond organ during a symposium on “Lift Every Voice and Sing” at the Museum of the Bible on June 12, 2025. RNS photo by Adelle M. Banks

In its early years, it was pasted on the back of hymnals, Bibles, and schoolbooks and was sung regularly at NAACP and other organizational gatherings. Words from its second stanza were recited in the benediction of President Barack Obama’s first inauguration in 2009, and in the sermon at the inaugural prayer service the next day: “God of our weary years/God of our silent tears,/Thou who has brought us thus far on the way.”

In February, Grammy Award-winning vocalist Ledisi performed the anthem with 125 high schoolers during the Super Bowl pregame ceremony to mark the 125th anniversary.

During his remarks, Thorpe ticked off a range of artists who have recorded versions — some known for gospel music and some not — Ray Charles, Aretha Franklin, Alicia Keys, and Mary Mary.

“‘Lift Every Voice and Sing’ remains one of the most powerful symbols of the Civil Rights Movement,” he said. “It is featured in over 40 different Christian hymnals and sung in churches all across America, not just during Black History Month or Juneteenth.”

Over the course of the day and evening, some 200 audience members heard the song performed by a wind ensemble, sung in an array of arrangements by choirs, played on the Hammond B-3 organ, and featured in a spoken-word performance.

“It resonates not only in different genres, but it resonates in even different generations,” said Bobby Duke, the museum’s chief curatorial officer, in an interview. “We have seen people that are very much senior citizens, when they heard the Duke Ellington (School of the Arts) choir start singing, they stood. We see college students and then even students that are still in secondary school singing this.”

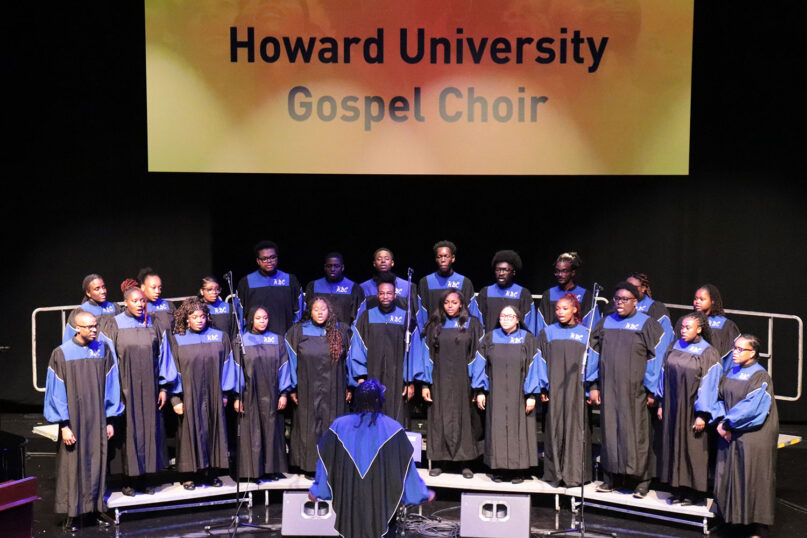

The Howard University Gospel Choir performs during the Lift Every Voice and Sing event. RNS photo by Adelle M. Banks

Duke collaborated with Bishop David D. Daniels III, a scholar of historical African and Black Pentecostal contributions to Christianity, who envisioned the symposium before his Oct. 10, 2024, death. The event, which was dedicated in memory of Daniels, received funding from the Phos Foundation, which is co-directed by Virginia Gov. Glenn Youngkin and his wife, Suzanne.

The symposium featured discussions of the three-stanza text — often all three are sung in churches and performances — and the music that accompanies it. Religious leaders and scholars, including the Rev. Joy Moore, president of Northern Seminary outside of Chicago, discussed its words of hope and of lament.

“The text of this song doesn’t just say, as African Americans, we are in pain,” she said. “But it says, from this experience of pain, we hold this hope passed down to us, and we pass it on so that we are faithful to who we are and to the God who has created us and called us and not given up on us.”

One audience member, the Rev. E. Daryl Duff, a retired Navy musician, described an instance where the song was not accepted by a white member of a chorus he directed at Fort Belvoir in Virginia.

“She was a solid choir member until February, when I would program this song, ‘Lift Every Voice and Sing,’ and she saw it as a divisive song,” Duff, who is Black, told the panelists. “How do we as a people, Black, white, Jewish, Chinese, Japanese, make this song ubiquitous, which I believe that’s what God wants?”

Chelle Stearns, a white professor at Seattle School of Theology & Psychology and a symposium panelist, said in response: “Two words come to mind: curiosity and friendship. And I think we need a lot more of that.”

Journalist Kevin Sack, author of a new book about Mother Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina — where nine church members, including their pastor, were murdered by a white supremacist in 2015 — wrote about being moved by two particular lines of the song. Back in 2019, he stood next to a septuagenarian church member, whose eyes filled with tears as congregants sang: “We have come over a way that with tears has been watered/We have come, treading our path through the blood of the slaughtered.”

“It just blew me away at how directly relevant it was to what had happened, literally one floor below where we’re standing,” Sack recalled in an interview with Religion News Service the day after the symposium.

Sack, who is Jewish and has spent many Sundays at Mother Emanuel, said he considers the song the nation’s best anthem.

“I give the Johnsons credit because obviously I don’t know that it was their intent, but I do think that it is a piece of music that communicates powerfully to white listeners as well as to Black listeners,” Sack said.

Symposium organizers and participants noted their desire for the anthem to continue to bridge ages as well as races.

“It’s transferable to not only many genres, but it’s transferable to the generations,” said Stephen Michael Newby, a music professor at Baylor University in Waco, Texas, pointing to the popular concert version of the anthem arranged by musician Roland Carter and performed across Europe and America, including by the Duke Ellington high schoolers at the symposium.

Prince Francis, 13, a member of the Washington Performing Arts Children of the Gospel Choir, which sang a gospel-style version, agreed. After the event, he said he liked the “powerful meaning” of the song.

“To me, when it says, “Lift every voice and sing ’til earth and heaven ring,’” he said, “you want people to sing with you and come together.”