BEARING WITNESS: What the Church Can Learn from Early Abolitionists. By Daniel Lee Hill. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2025. Xiv + 190 pages.

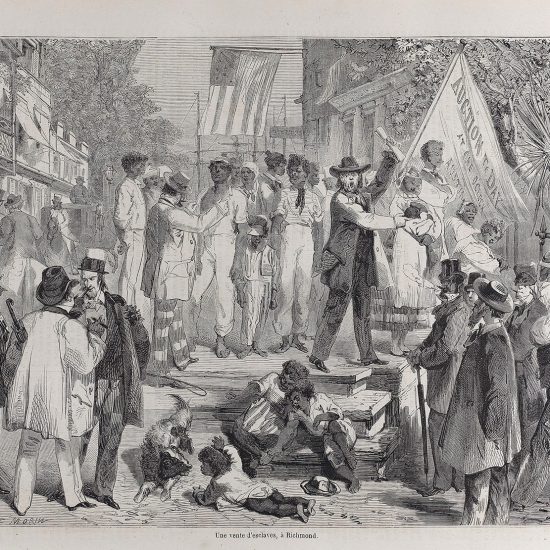

Jim Wallis called slavery America’s original sin. Although many Americans would like to forget or diminish the impact of the sin of slavery on American life and history, the stain remains present on American life. During the years that slavery existed in the United States, movements of abolition rose up, calling attention to this stain. These abolitionists represented various religions and ideologies, but they held in common the belief that slavery was a form of evil that must end. Many people in the United States, especially White evangelicals and supporters of Trump’s MAGA movement, in its effort to rid the country of DEI (Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion), would like to forget the past or at the very least create a version of the past where the United States remains unstained by such sins. If we choose to take a different path, one that acknowledges the sins that stain our history, might the church learn something from early abolitionists, especially if they were Black? In learning from these abolitionists as they stood against the sin of slavery, might the church learn something about its own public witness?

Robert D. Cornwall

Questions about slavery and abolitionism stand at the heart of Daniel Lee Hill’s book, Bearing Witness: What the Church Can Learn from Early Abolitionists. Hill, who holds a Ph.D. from Wheaton College and serves as an assistant professor of theology at Truett Theological Seminary, seeks to retrieve resources from America’s abolitionists, while thinking theologically about the church’s public witness in the present and future. Hill approaches these two concerns from a particular vantage point. First, he is an African American, and second, he is an evangelical Christian. From that vantage point, Hill seeks to call evangelicals back to a form of public witness that seeks the common good. One note on terminology, throughout the book, Hill uses the descriptor Afro-American. Since that is his choice of descriptors, I will use it in the remainder of the review.

In the first section of the book, which Hill titles “Giving the Faithful Dead a Vote,” Hill focuses on the witness offered by three Afro-American abolitionists: David Ruggles, Maria Stewart, and William Still, three figures who lack the name recognition of a Frederick Douglass or Sojourner Truth, but whose contributions are worthy of note. In the four chapters in Part 1, Hill invites the reader to listen to their ancestors, in this case, nineteenth-century Afro-American evangelicals who offered a public witness that addressed the evils of slavery. As we reflect theologically on the work of these ancestors, Hill reminds us of the need to keep in mind their context and the ways they responded. We also must remember the past faithfully, such that the community continually undergoes reformation. In choosing these three figures, to each of which Hill devotes a chapter, he notes that they all share a common social location — the nineteenth-century antebellum United States.

Hill begins Part 1 of the book by offering the reader a historical introduction (chapter 1) that sets up the conversation as it moves forward. In this chapter titled “Freedom in the Time of Slavery,” Hill wants to help address the strangeness of nineteenth-century America, with its institution of slavery, and the attempts to find freedom in such a context. Along with the descriptions of slavery in the United States, Hill describes the larger abolitionist movement. He helps us better understand both the stain of slavery and the men and women who stood against it as they engaged in an improvisational effort (Chapter 1). As Hill moves on to chapter 2, he takes up the story of David Ruggles. The subtitle to this chapter is “Learning to Read and Imagine the World.” Ruggles was a free-born Afro American abolitionist who lived and worked largely in New York City, advocating for fugitive slaves and opposing efforts to kidnap fugitive slaves while also advocating for free-born or emancipated Afro Americans. Then, in Chapter 3, subtitled “Nurturing the Seeds of Change,” he focuses on Maria Stewart, who presents a very interesting face to the abolitionist movement. She was known as a writer who encouraged the building of new institutions and renewing old ones, but most of all, she focused on creating communities of character. The third figure is William Still, whose life and work is explored in chapter 4. Still was involved in the Underground Railroad in Philadelphia, documenting every fugitive who came through Philadelphia on their way to freedom. His work provides an important record of the work of abolishing the evil institution that was slavery. As such, Hill writes of William Still that he “reminds us that we need to be people who continually look backward in remembrance, understanding memory as a necessary resource for navigating life in the present” (p. 110). Each of these three figures has a different story, but each contributed significantly to the struggle to overcome America’s original sin.

While Hill wants us to remember figures from the past who exemplify resistance to slavery, he also wants to speak to the present and future. So, after we examine the lives of these three important figures who are not as well-known as Douglass or Harriet Tubman, their stories provide us with important information about what it means to bear public witness for justice. Having shared the stories of the three abolitionists, Hill moves in Part 2 to “The Twofold Work of Public Witness.” In this section, Hill seeks to engage in theological construction using readings from Romans 8 and Galatians 5-6, together with the witness of the three historic figures, to provide the foundation for an evangelical public witness that pursues the common good. This section provides two chapters. The first chapter (Chapter 5) is titled “Lament as Public Witness.” In this chapter, Hill lifts up the church’s witness in the midst of “suffering, futility, and decay.” In doing this, Hill seeks to call the church to engage in lament over the nation’s sins so that it might offer the world a word of hope. Then in Chapter 6, he addresses the church’s “Burden bearing as public witness.” Thus, even as the church engages in lament, it also joins with the Holy Spirit in bearing the world’s burdens. This involves sharing in the common good and in temporal goods. He writes that “one of the primary ways that Christians attest to the freedom that God has opened up for them in the person of Christ is by seeking their neighbors ‘good.’” (p. 142). This involves, he believes, three things: extending, preserving, and cultivating temporal goods. The point here is that the church is not just called to engage in “spiritual things” while neglecting common temporal goods. By doing this, the church offers public witness to God’s realm — something the three figures did in their own context.

Hill has a specific audience in mind. He hopes to speak to fellow evangelicals, calling for them to embrace the principles he finds in the historic past among Afro-American evangelicals. While evangelicals are the target audience of the book, Hill offer the larger church a message rooted in scripture and history that needs to be heard by all Christians whatever their tradition at a time when many wish to embrace a mistaken view of the past that has implications for the present, especially if you are a black or brown person. As I noted above, the implications of Hill’s thesis address the kinds of propaganda that many are offering people in the United States as if it were actual history. Such efforts not only distort history they also distort the mission and message of the church in the United States. Therefore, Daniel Lee Hill’s Bearing Witness is a book that needs to be read and pondered if Christians are to fulfill their calling.

This review originally appeared on BobCornwall.com.

Robert D. Cornwall is an ordained minister in the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ). Now retired from his ministry at Central Woodward Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) of Troy, Michigan, he serves as Minister-at-Large in Troy. He holds a Ph.D. in Historical Theology from Fuller Theological Seminary and is the author of numerous books, including his latest “Second Thoughts about the Second Coming: Understanding the End Times, Our Future, and Christian Hope” coauthored with Ronald J. Allen. His blog Ponderings on a Faith Journey can be found here.