NOTE: This piece was originally published at our Substack newsletter A Public Witness.

“An unhealed past is why we find ourselves mired in an uncertain and unstable present. And yet, we are not without hope.”

Rev. Traci Blackmon, a United Church of Christ minister in St. Louis, welcomed Baptists to her city with that call to remember the past and reimagine the future. Speaking on June 25 during the general assembly of the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship in the shadow of the Arch, Blackmon urged the CBF attendees to remember the stories of racist injustices too often overlooked and paved over.

She noted that the St. Louis Cardinals baseball stadium — where many at the CBF gathering would go that evening to watch a game — was built on the site of the city’s most notorious slave pens. Thousands of people were held in captivity there ahead of being sold, with families publicly separated as some were sent down the Mississippi River just over 1,000 feet away from where she spoke. The remaining pens were torn down in 1963 to make way for the stadium.

Blackmon also noted that across the street from the conference hotel sits the old courthouse where “stolen people were marched to be auctioned off on the steps that face this hotel.” With those steps facing the river, those enslaved people “could see clearly over across the river to Illinois, which means that those who were being auctioned off as slaves were looking at freedom while listening to the bids for their lives.” The infamous Dred Scott case — in which the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that people of African ancestry couldn’t claim citizenship — started in that courthouse.

Gathering “under the shadow of all this history,” Blackmon said, should remind them that “though this moment seems like we are reversing in time, the truth is if we face our stories and we tell the truth and we commit to building a different kind of world, another world is possible.”

“If your theology doesn’t make you do something, it is not of God,” she added. “If your Jesus only saves your soul and not your neighborhood, that ain’t the gospel. If your faith keeps you comfortable while others are crucified by systems, you need to read the book again. It is time to repent from and reimagine what following Christ really means.”

Left: People gather during a session of the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship’s general assembly in St. Louis, Missouri, on June 26, 2025. Right: Traci Blackmon speaks at the gathering on June 25, 2025. (Brian Kaylor/Word&Way)

Blackmon added that she hoped seeing not just the beauty of St. Louis but also “our hidden secrets” and “the things that we need to uncover” would inspire people to “go back to your places and work to uncover those same kinds of things in your own community.” Thus, she called for those attending the CBF gathering to do the work of combating historic and ongoing injustices.

“Now is the time to rise in sacred resistance. Now is the time to declare the boldness that the night is far gone and the day is near. Patience is a luxury of privilege,” she declared. “We have to act on what we know is true about the God that we serve.”

“We are not powerless; we are prophetic. And now is the time for us to stand together, to sow together, to rise together. Let me be clear: The world is on fire. Democracy is being dismantled. Theologies of empire are masquerading as faith. The state is scripting sermons, banning books, criminalizing truth. But I hear a sound of Pentecost rising in the voices of our children, a freedom cry rising,” she added. “The spirit of the Lord is upon us to preach good news to the poor, proclaim the release to the captive, to recover sight for the blind, to let the oppressed go free. We are not waiting for a move of God; we are the move of God.”

While the Southern Baptist Convention receives most of the media attention, other Baptists are working ecumenically to combat racist injustices. The Cooperative Baptist Fellowship — the longtime denominational home of the late Jimmy Carter — is one such group. They are even suing the Trump administration to block immigration raids in houses of worship. So this issue of A Public Witness takes you inside the recent CBF annual gathering to consider how Christians can speak truthfully about the past and speak truth to power today.

Retelling the Past

Like Blackmon, Robert P. Jones of PRRI talked about American slavery and St. Louis. He noted that his latest book, The Hidden Roots of White Supremacy and the Path to a Shared American Future, opens with a story on the river in St. Louis. Robert Hickman, a Black Baptist preacher, had freed himself, his family, and some neighbors from a plantation in Boone County in the middle of the state in 1863. After they had floated down the Missouri River amid the Civil War, their raft ended up on the Mississippi River which connects with the Missouri River in St. Louis. There, a steamboat captain heading north to Minnesota agreed to tow them along. Once in Minnesota, the group of Black refugees immediately faced racism and witnessed genocidal government actions against Native Americans.

Jones urged those present to consider the various threads woven together in the story of St. Louis. A city named for a Catholic king on land previously called Mound City because of the numerous Native American mounds there. Those mounds were virtually all leveled to build the city. The Arch, constructed as part of the “Jefferson National Expansion Memorial,” now marks this place like “the portal of Manifest Destiny” on “occupied land.” Noting that the Osage people lived here before being forced to move to Oklahoma, Jones added, “Maybe you’ve seen or read the book Killers of the Flower Moon or heard the saga of the Osage in Oklahoma, but before we screwed them over in Oklahoma, we screwed them over here.”

“It’s not an exaggeration to say that in all of America, we have testimony that we’re living among a crime scene,” he added. “We have these things all around us, and we have to kind of figure out a way to reckon.”

Jones encouraged churches to reckon with this past by retelling their church histories to document participation in racial injustices. He mentioned how usually the “glossy volume sitting on the church library shelf” lifts up the congregation’s founders in a “rose-colored glasses kind of story.”

“Let’s go back and tell the real story right about what happened here,” he added as he urged churches to address both how they got their land and ties to slavery and other racist injustices. “It changes the story you tell and memory again becomes a kind of salvage operation here.”

During the opening worship service, one pastor modeled what Jones called for. Melissa Hatfield, lead pastor at First Baptist Church in Jefferson City, opened her message by telling a story of a faithful Baptist couple who ministered and challenged slavery in St. Louis. John Berry Meachum, who had bought his own freedom, came to the area after the enslaver of his wife, Mary, and their two children moved from Kentucky to St. Louis — where he eventually purchased their freedom. In 1827, John became the founding pastor of the First African Baptist Church in St. Louis (now known as First Baptist Church). Additionally, the Meachums helped people gain their freedom as part of the “Underground Railroad,” using their earnings to free people and helping people escape into the free state of Illinois.

John also started the first known school for Blacks in Missouri, but state lawmakers in 1847 banned any education for Black people and police shut down the Candle Tallow School. Undeterred, John created the “Floating Freedom School” on a steamboat, holding classes on the Mississippi River since that was under federal jurisdiction outside of state laws.

“Radical hospitality afloat just beyond the reach of unjust laws,” Hatfield said about the floating school. “When Missouri said, ‘You don’t belong,’ John Meachum said, ‘Come to the waters.’”

Hatfield then told a different kind of story, that of her church “130 miles west of here.” Formed in 1837 near the Missouri River, she lamented that “there were no steamboats of resistance along our stretch of the river.”

“In fact, our early story includes at least four pastors who were themselves enslavers. Three went on to serve the Confederacy,” she added. “Among our chartered members are enslaved persons: Jenny, Adams, General, Milly, Phillis, and Louis. And so many others whose names we will never know. While the Meachums were up here risking everything for liberation and belonging, our church was silent or, worse, implicit. I say that not with shame but to name it. Because healing begins by telling the truth. Our story, your story begins there — not where we are, but where we’ve been, and, more importantly, where God is taking us. For the spirit never stops calling to us and saying, ‘Come to the waters.’”

“That’s our call: To cultivate a holy, alternative, liberated imagination. To be steamboats of belonging, faithfully living out our call regardless of unjust laws who deny the rights and worth of some people. To be a fellowship soaked in grace with a different vision. To be churches full of courage, even when the waters are murky,” Hatfield added.

From left: Robert P. Jones, Melissa Hatfield, and Angela Denker speak at the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship’s general assembly in St. Louis, Missouri. (Brian Kaylor/Word&Way)

Angela Denker, a Lutheran minister and journalist who wrote Disciples of White Jesus: The Radicalization of American Boyhood, also practiced what other speakers did throughout the week as she talked about the importance of not just calling out “other churches” for racism, patriarchy, and Christian Nationalism but also being willing to look at her own ELCA Lutheran tradition for confession and repentance.

So she talked about traveling to South Carolina to write in her book about Dylann Roof, the White supremacist who killed nine Black people during a Bible study at Mother Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina, a decade ago. Denker not only visited that church but also the ELCA Lutheran church where the shooter grew up.

“The tendency that I wanted to guard against is this tendency that I see over and over again in White Christian spaces. It’s this tendency to want to immediately distance ourselves from that which we would consider abhorrent or problematic. I see it happen so often in conversations around racism, conversations around how racism continues to be active in our politics,” she added. “So there’s this tendency to look at something that we would consider to be really bad and say, ‘Well, this is how I’m not like that, this is how that has nothing to do with me, I’m not racist.’ Rather than really confronting the ways in which racism is baked into our churches in ways that don’t necessarily have to do as much with individual sin as that have to do with structural sin.”

Help sustain the journalism of Word&Way by subscribing to A Public Witness!

Finding the Courage to Act

In addition to considering ways churches and our broader society have been complicit in racism and other injustices, speakers throughout the CBF general assembly also encouraged those present to mobilize for justice today. As Amanda Tyler of the Christians Against Christian Nationalism campaign led a session about the dangers of Christian Nationalism, she emphasized the need for Christians and churches to get involved, especially given the rise in political violence and harmful public policies inspired by nationalistic ideology.

“It’s up to us and our churches and in our conversations to roundly reject violence in all forms as being against the gospel, as against anything that Jesus ever stood for,” explained Tyler, author of How to End Christian Nationalism. “Jesus was inherently political. And I don’t mean that in a partisan sense. Jesus was not a Democrat or Republican. … But Jesus was political in the sense that he cared about the life of his community and he got involved in justice work to try to change the living conditions of those who were oppressed and marginalized by power.”

Similarly, Paul Raushenbush, president and CEO of Interfaith Alliance, told of his own personal journey of faith and finding a slice of Christianity welcoming to everyone before urging people to advocate for those under attack today. An American Baptist minister, Raushenbush pressed the crowd to not let rights be taken away from him or others.

“We are living in dangerous times. The Southern Baptists just recently passed a resolution that essentially declares war on same-sex marriage and LGBTQ families like mine. Pride Flags in front of churches are being torn down all across the country,” he said. “All across the country there are bills attacking and attempting to erase trans people as well as normalizing violence and legalizing discrimination against LGBT communities. The current Administration with its so-called anti-Christian bias task force is relentlessly attacking any Christian group that is not in lockstep with an authoritarian White Christian Nationalist agenda. Our freedom of religion is under attack.”

“I’ll be damned if I will allow anyone to take my church or my tradition away from us,” he added. “Now is the time for courage. The root of the word ‘courage’ is ‘core’ or ‘heart.’ Jesus commands us to love and transform that love into courage required to show up for one another, with one another in this time.”

From left: Paul Raushenbush, Amanda Tyler, and Brian Kaylor speak during the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship’s general assembly in St. Louis, Missouri. (Word&Way)

One way CBF as a denomination is practicing the call to speak out is by suing the U.S. Department of Homeland Security to block immigration raids in houses of worship. The lawsuit, which is ongoing, led to an injunction that currently blocks such raids at CBF churches (as well as Quaker congregations and a Sikh temple).

The lawsuit came up frequently during the CBF gathering, including in fiery remarks from CBF’s outgoing moderator, Juan García. The pastor of Primera Iglesia Bautista in Newport News, Virginia, García closed his time leading CBF with remarks delivered in Spanish (with an English translation on the screens) in which he lifted up the “important and courageous” legal advocacy against the Trump administration. Calling on the crowd to be “faithful dissenters” and “tireless defenders of justice and love,” he urged them to “defend the dignity of immigrants, the hungry, the homeless, the poor, the elderly, the marginalized,” and anyone else “dehumanized and demonized by elected officials.”

“This is what has characterized us from the beginning. At the heart of our Baptist identity is a commitment to dissent,” he said. “Our ancestors dissented against the idea that governments should control the church. They dissented against the notion that faith could be imposed by force instead of freely chosen. … That dissent was costly. Many of our ancestors were persecuted, imprisoned, and even killed for their convictions. Yet, their courage paved the way for us to be gathered here today, worshipping and living our faith freely.”

“Brothers and sisters, we are called to dissent against any ideology that seeks to replace Christ — his way, his truth, and his life — with political power, nationalism, lies, or fear. … We are called to dissent against systems that exploit and exclude. This dissent is not optional — it is foundational to those who follow Christ, who embraced and included all, especially those whom social systems rejected and excluded,” García added. “The Lord Jesus himself was the great dissenter — challenging the religious and political powers of his time, refusing to bow to empire, lifting the lowly, and calling his disciples to a king of love, justice, and peace that looked nothing like Rome and its so-called Pax Romana. Cooperative Baptist Fellowship, this is the moment to rise with courage, lift our voices, and act.”

After García closed, the crowd at the CBF gathering gave him a standing ovation that lasted for more than a minute.

As a public witness,

Brian Kaylor

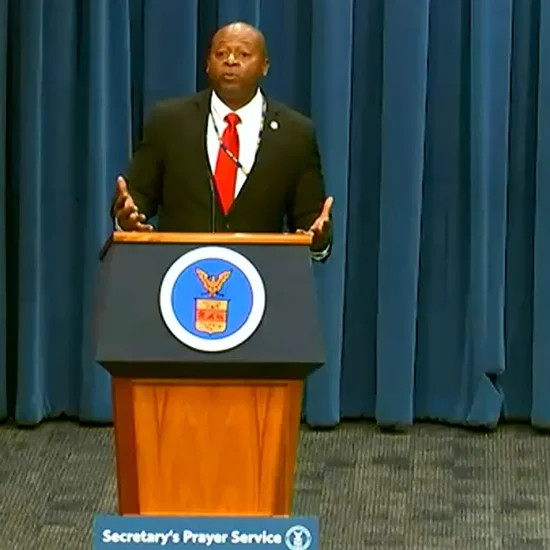

Outgoing Moderator Juan García speaks during the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship’s general assembly in St. Louis, Missouri, on June 26, 2025. (Brian Kaylor/Word&Way)

A Public Witness is a reader-supported publication of Word&Way. To receive new posts and support our journalism ministry, subscribe today.