(RNS) — W. James Abbington Jr., an expert on Black religious music known for his editing, teaching, and playing of congregational music, has died at the age of 65.

GIA Publications, for whom he worked for more than two decades as executive editor of the African American Church Music Series, announced Abbington died on Saturday (Sept. 27).

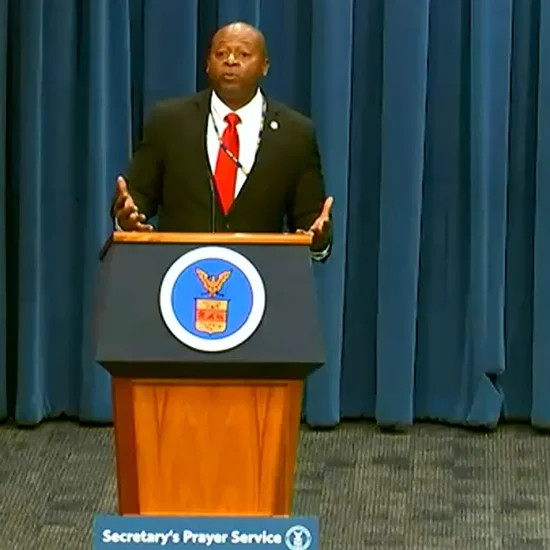

James Abbington in a video for Emory University’s Candler School of Theology. (Video screen grab)

“Jimmie was our friend and colleague for more than 25 years and he will be greatly missed,” the Chicago-based publisher said on Facebook. “Jimmie was a connector and a mentor in the truest and deepest sense of those words, always taking the time to encourage young musicians and composers, particularly those of color, to reach the heights of their education, celebrating each individual’s accomplishments at every step, and continuing to support their professional work.”

Abbington was a former associate professor of church music and worship at Emory University’s Candler School of Theology, serving on its faculty for two decades. As of July 1, he had taken on a new role as the first person appointed Joseph B. Bethea Professor of the Practice of Sacred Music and Black Church Studies at Duke Divinity School.

He played the piano and sang during a July event at the Durham, North Carolina, school, and had intended to return to campus for the fall semester. But, the school said, he suffered complications after a medical procedure. He died in Georgia.

“The news of the passing of Dr. Abbington has, in the words of Psalms 22, melted my heart. I grieve for his family, friends, and our Divinity community,” said Edgardo Colón-Emeric, dean of Duke Divinity School, in a statement. “We dreamed dreams with our first Joseph B. Bethea Chair, and we will miss the professor, the performer, and the person.”

Stephen Michael Newby, music professor and ambassador for Black gospel music preservation at Baylor University in Waco, Texas, said Abbington “served as the dean of African American church music.” His reach included the written music he published through GIA and the church musicians he trained in conferences, especially the academy of the ecumenical Hampton University Ministers Conference. The Hampton Choir Directors’ and Organists’ Guild named that annual academy in Abbington’s honor in 2010.

“His loss is tremendous,” said Newby, who was a fellow student pursuing his doctorate in music arts with Abbington at the University of Michigan in the 1990s.

Newby recalled how Abbington influenced up-and-coming church musicians to grow in their appreciation of the music they led but also in their faith: “He has discipled hundreds and hundreds of the next-generation worship pastors, organists, pianists, church musicians.”

Among his many publications, Abbington was the author of “Let Mount Zion Rejoice: Music in the African American Church.” He was also a member of the editorial committee of the African American Heritage Hymnal.

Abbington was named a fellow of the Hymn Society of the U.S. and Canada, the organization’s highest honor, in 2015 and was a panelist in its online roundtable discussion on congregational song in May.

Brian Hehn, director of the society’s Center for Congregational Song, said Abbington’s passion for teaching joined with his “brilliance” in playing “anything with keys” — including piano and organ.

“Part of you wanted to sing with him because it was so inspiring, and the other part of you didn’t want to sing because you just wanted to listen to him, the brilliance of what he was playing,” Hehn said.

The African American Church Music Series, with its sheet music offerings, widened the reach of Black church music beyond Black churches, Hehn said.

“It was giving opportunities for all these amazing composers who deserved to be published,” Hehn said. “He made sure they got published, and then that music was then accessible to people who didn’t grow up in the Black church and who maybe couldn’t play in that style by ear.”

In a 2003 interview with Reformed Worship, a journal of the Calvin Institute of Christian Worship, Abbington emphasized that the series was for all singing voices, not just African American congregations.

“It was never intended to be a series exclusively for African Americans, but all the composers are African American,” he said. “This is not ‘our’ music; it is music for the whole church.”

The Samuel DeWitt Proctor Conference, an organization that supports African American ministries, honored Abbington with its “Beautiful Are Their Feet” award in 2019, noting his being raised as a Pentecostal, his role as an organist at prominent Black Baptist churches, and his understanding of the power of spirituals as well as modern-day gospel music. The conference’s leaders expressed “sadness and shock” at his death.

“There was no one like him,” said the Rev. Iva Carruthers, general secretary of SDPC, in a statement. “(Dr. Abbington) was not just a teacher or a musician; he was an instrument of God, able to usher in a spirit of hope, power, and joy whenever he did what God had clearly called him to do. As an ethnomusicologist, editor of the African American Church Music Series of GIA Publications, and mentor to so many, his contributions to the Proctor Conference were unique.”

The Rev. Jeremiah A. Wright Jr., an SDPC co-founder and close friend of Abbington’s, added: “When you experienced Dr. Abbington in a class setting or in a worship service, your soul would shout in awe or whisper in breathless adoration, ‘To God be the glory for the things He has done!’”

In the inaugural issue of The Yale ISM Review, Yale Divinity School’s Institute of Sacred Music magazine, Abbington argued against those who suggest spirituals are merely “simple little songs” without theological relevance.

“These sacred folk songs are biblically based, theologically astute, culturally relevant, accessible, and provide a tremendous liturgical vehicle for full, conscious, and active participation in worship,” he wrote in 2014.

Abbington also spoke of different genres of church music and the ways they were interpreted by hymn lovers and composers over generations.

He once told Religion News Service that the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s emphasis on hymns in his sermons demonstrated that lyrics became more important to the civil rights leader than the musical notes that accompanied them.

James Abbington at the piano. (Photo courtesy of GIA Publications)

“King was a trained theologian,” he said in the 2012 RNS interview. “Music becomes the platter or the handmaiden for theology.”

In a 2021 video released by Candler School of Theology, Abbington described how the lyricist David G. Frazier’s simple words from the song titled “I Need You to Survive” were accessible as a congregational song shortly after 9/11 and became a global sensation.

“He was very intentional about singing it in unison and also using very simple chords, so that people in the congregation would not be intimidated to sing it together,” Abbington said, “but that it actually became a song of fellowship.”

Abbington noted that the influence of a church song is not rooted in whether it is traditional, contemporary, or reminiscent of a secular tune.

“It is important to remember that it is not about casting a judgment or value of this is high, this is low, this is secular sounding, this is sacred sounding,” he said. “But let’s see what is the text saying to people in the times. And trust me, a good tune will carry a great text.”