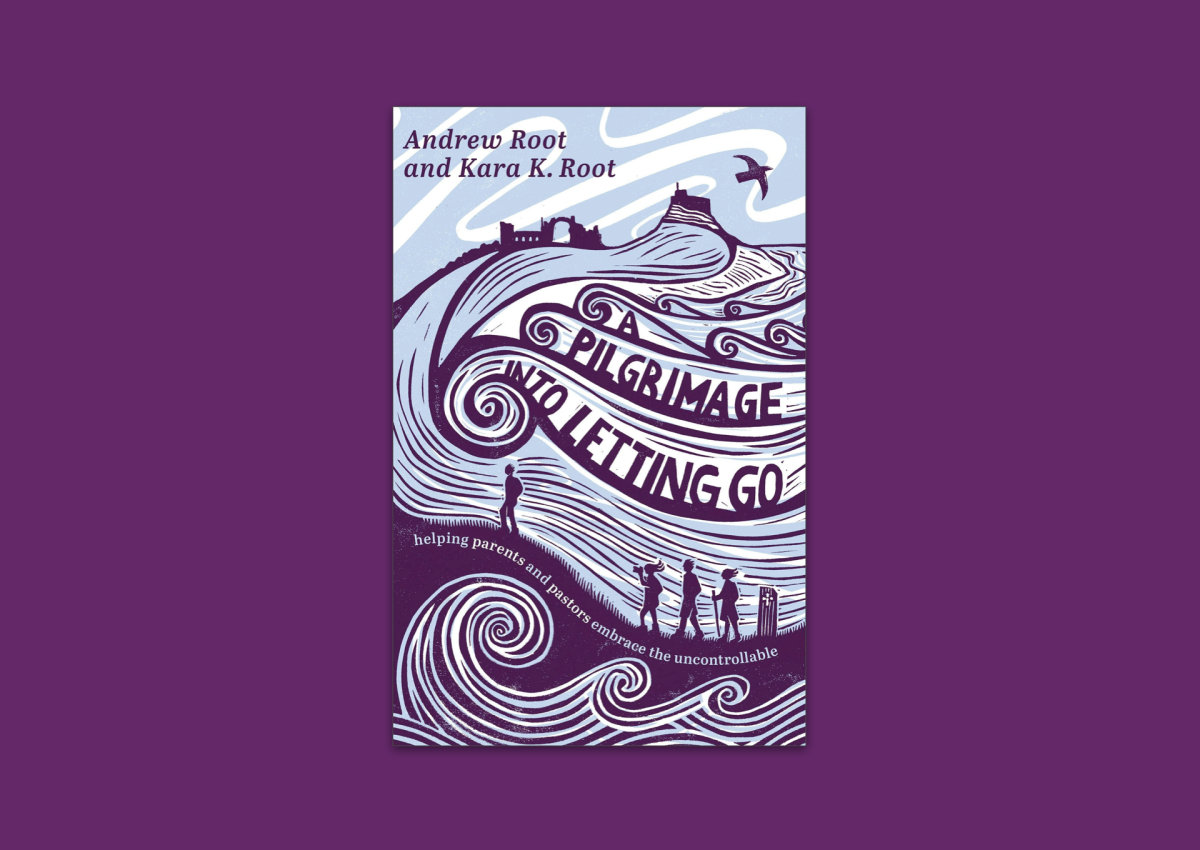

A PILGRIMAGE INTO LETTING GO: Helping Parents and Pastors Embrace the Uncontrollable. By Andrew Root and Kara K. Root. Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos Press, 2025. Ix + 230 pages.

Human beings often feel most comfortable when they are in control of their lives and context. At least that is true for me. I would like to know where I am going and how I’m going to get there. I don’t think I’m a control freak, but like many people, I struggle with the uncontrollable. Unfortunately, there are too many things and people that stand outside our control. That can cause frustration, anxiety, anger, and more. While much of life is uncontrollable, how do we let go of this need to control, whether we’re parents or even pastors? I will note that I am a parent of an adult son and a retired pastor, so I have experience with both realities. The question is, would a pilgrimage help us let go of the uncontrollable?

Robert D. Cornwall

The question of letting go of the uncontrollable in the context of a pilgrimage is the subject of the latest book by Andrew Root, this time co-authored with his spouse, Kara. They titled the book A Pilgrimage into Letting Go, which has as its subtitle: Helping Parents and Pastors Embrace the Uncontrollable. Many readers of this review will know the name Andrew Root, who is the Carrie Olson Baalson Professor of Youth and Family Ministry at Luther Seminary. They may have read one or all of the books in his Ministry in a Secular Age. I have read and reviewed most of the books in that series, which I have found to be very helpful. Perhaps they know of his spouse, Kara, as well. She is, for her part, the senior pastor of Lake Nokomis Presbyterian Church in Minneapolis and a spiritual director/certified educator in the PCUSA. She is also the author of several books, including The Deepest Belonging and Receiving This Life. I will confess that while I’ve read Andrew’s books and have met him and know him to be an excellent presenter, I do not know Kara’s work.

In A Pilgrimage of Letting Go, the Roots draw upon Hartmut Rosa’s book The Uncontrollability of the World to provide a philosophical framework for the book. With that as the foundation, they bring into the conversation their experiences of a family pilgrimage that took them from the village of Melrose, Scotland, in the Scottish Borderlands, through northern England, to the holy island of Lindisfarne. The journey the family took followed the path taken by St. Cuthbert in the eighth century CE. As they reflect on their experiences during their pilgrimage, they ponder the challenge of letting go of their need to control the uncontrollable. As the subtitle of the book notes, this is a book that speaks to challenges faced by parents and church leaders, especially pastors. They point out that both parents and pastors can feel the need to be in control, either of their children or their congregations. The intentions might be good, but the downside is significant because neither children nor congregations are controllable.

A theme that runs through this book is one that readers of Andrew Root’s previous books will have already encountered. That theme involves the anxiety we often feel because of the way life seems to be accelerating, while we seem unable to keep up. Unfortunately, slowing down may not help. At the same time, following Rosa, the Roots speak of the importance of resonance serving as an antidote to acceleration. Yet even here, there are challenges. Resonance, we learn, involves a feeling of being alive, of being awake, and of having a feeling of connection to something. There are, we’re told, four traits to resonance. First, he writes that “something from outside us ‘calls’ to us.” Secondly, there is the need for a response to that call, what Rosa calls “self-efficacy.” Third, he speaks of transformation, which accompanies resonance. Finally, resonant experiences are uncontrollable. That is, we are not in a position to cause resonant experiences to happen. It is this fourth element that is most important, and is the element that the authors seek to develop in this intriguing book.

If you’ve read Andrew Root’s books, you will know that they can be dense at times, especially as he engages with philosophers and social theorists such as Charles Taylor and Hartmut Rosa. Because this is a jointly authored book, the authors can bring together Andrew’s understanding of social theory and theology with Kara’s experiences as a pastor and spiritual director. The pastoral element shows through in several places, making this a delightful read. The personal experiences of the family, including times of frustration, as they take their pilgrimage, add to the more experiential nature of the book.

The titles of the chapters give us a sense of what we will find in this book, a book that combines social commentary with accounts of the pilgrimage the family takes as they journey to Lindisfarne. We get to hear about the ups and downs of their journey, which was successful (they made it safely to Lindisfarne), but at times it was stressful. The stressful parts often emerged when they tried to control the uncontrollable. So, the chapters begin with a conversation about “Control-Freak Parenting,” something parents can resonate with. Then we get to “The Thrill of Uncontrollability.” Experiencing the uncontrollable might be thrilling for a moment, but again, it is anxiety-producing. The third chapter is titled “Get Aggressive, Get, Get Aggressive.” It is in this chapter that the authors begin sharing about the pilgrimage following the path trodden by Cuthbert, a saintly monk who served as the bishop of Lindisfarne, and whose story was told by the Venerable Bede. It is in this chapter that the Roots begin discussing a growth mindset that easily takes hold of our lives. For example, we find ourselves believing that if we don’t grow our churches, they will die (that is a feeling many pastors of small churches experience). We then respond by trying to do everything we can to produce growth, even though it is uncontrollable. We do the same thing with our children as we seek to give them all the resources they’ll need to succeed in life, believing that if we don’t, they will fail. I think many parents understand that feeling.

After an interlude in which Kara shares with the reader a service of Morning Prayer she developed for their journey, we come to Chapter 4, which is titled “Grow, Grow, Grow.” The authors begin by sharing another element of their journey before getting into the topic at hand, the desire for growth. They introduce a new term here, “dynamic stabilization.” “Dynamic stabilization” involves the sense that life is stable only when it is growing. Of course, as we’ve learned in other Root books, growth requires innovation. Innovation demands that we control the uncontrollable, even if that means controlling God. We do this in several ways. First, we make the world visible, then reachable. From there, we make the world manageable. Of course, management requires control. Finally, we seek to make the world and the church, etc., “useful.” Even ritual and worship are defined by their usefulness. Of course, God is uncontrollable, and faith requires that we let go of our need to control God.

As we continue the journey, on Day 2, we come to a chapter titled “Losing Grip” (Chapter 5). Here, the Roots remind us that when we try to control the world, it withdraws from us. That is because the world is not an object that we can control. In this chapter, they contrast being a tourist, something that does involve control, with being a pilgrim, which involves something that breaks through one’s ability to control. So, the message here is that to be a pilgrim, we need to loosen the grip of control. That is because seeking to control life leads to alienation, which in turn leads to burnout and depression. Moving on to Day 3, in Chapter 6, we have “The Longest Mile.” You will need to read the chapter to fully understand the context, but in this chapter, the authors talk about the problem of “relationless Relating,” which emerges from the desire for instrumentalization and optimization, or to borrow from Buber, as they do, this is a question of an “I-It” kind of relationship in contrast with an “I-Thou” relationship.

When we arrive at Chapter 7, we hear the story of another day on the path St. Cuthbert took as he made his way to Lindisfarne. They title the chapter “Losing What We Never Had.” Here, they discuss the sense of control that we desire but have never had. They do note that there is room for semicontrollability, but not full control. One example here is prayer, which is semicontrollable because it involves a dialogue. We choose to enter the conversation, but we do not control the response. There are, however, barriers that exist to living this way. This chapter ends with the Midday Prayer service, which Kara Root also developed.

Moving on toward Lindisfarne, we encounter a new chapter (Chapter 8), which is titled “Haunted by the Frame: The Church, the Kids, and the Viking Raiders.” The last component, of course, involves the Viking raiders who devastated the monastery, driving the monks from the Island. The focus here is on understanding resonance and its relationship to desire or longing. They note, following Rosa, that desire cannot be controlled. Though our desires are not completely left to chance, they are shaped by culture, circumstances, and by us. The question then is how to shape desires. Parenting and pastoring involve helping people shape their desires well. Thus, “to shape our desire toward God is to shape our longings toward that which we cannot attain on our own” (p. 191). The final Chapter is titled “Door-knocking Demons and the End of It All” (Chapter 9). In this chapter, the Roots speak of the uncontrollability of uncontrollability. In doing this, they speak of the monsters we encounter in life, as well as on the pilgrimage. That is, our terror of the uncontrollable. Dealing with this requires trust, something that pilgrims understand because pilgrims do not control what happens along the way. The chapters end with Evening Prayer, another service put together by Kara Root.

In the Epilogue to Pilgrimage into Letting Go, the authors speak of the relationship of forgiveness to letting go. They point to the need for gentleness and acceptance of ourselves and others. They ask whether the journey of a pilgrim might be a “constant journey of forgiveness” (p. 226). That makes sense, but it does mean letting go of our need to control. If you have been reading Andy Root’s books, you will want to read this one as well. If you haven’t read him, this would be a good place to start. Including this personal story of their pilgrimage as a family draws the reader into the conversation, and the message is an important one for parents and for churches. With that, we are invited to ponder the possibility of letting go of the things we cannot control, whether children or churches, or the many circumstances that come our way in life. As many know, letting go of control is not easy, but the Roots believe that letting go allows us to find some sense of resonance in our lives. That is, most likely true. Thus, we can be thankful as parents and as pastors for this word.

This review originally appeared on BobCornwall.com.

Robert D. Cornwall is an ordained minister in the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ). Now retired from his ministry at Central Woodward Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) of Troy, Michigan, he serves as Minister-at-Large in Troy. He holds a Ph.D. in Historical Theology from Fuller Theological Seminary and is the author of numerous books, including “Eating With Jesus: Reflections on Divine Encounters at the Open Eucharistic Table” and “Second Thoughts About Hell: Understanding What We Believe” coauthored with Ronald J. Allen. His blog Ponderings on a Faith Journey can be found here.