By Patricia Mora, Word&Way Correspondent

Howard Crain retired to a rocking chair in 1980 and seldom leaves it — except to  warm a bottle. For 26 years, Howard, 80, and his wife, Benette, 75, have cared for infants in their small Independence home.

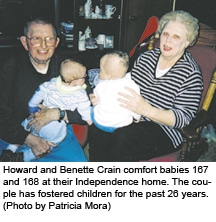

warm a bottle. For 26 years, Howard, 80, and his wife, Benette, 75, have cared for infants in their small Independence home.

"This is number 168," Howard said, rocking a fretting 7-month-old. On a blanket near his feet lay another baby, a pile of colorful toys within reach.

"The one Howard's holding is a meth baby," Benette said. "They need a lot of hands on. Meth withdrawal makes very fussy babies." Meth babies are infants whose mothers abused methamphetamines while pregnant. Newborns suffer through withdrawal.

"The other one is 18 days older. He's a little slow sitting up and rolling over, so he gets physical therapy. He's not fussy at all," she added.

Howard and Benette each take responsibility for one baby. If Howard's baby cries in the night, he gets up. If it's Benette's baby, she gets up. Benette normally takes the younger infant. "Usually we have one about six months and a newborn."

Though Benette has arthritis and Howard had quadruple bypass surgery two years ago, both appear as agile and alert as people decades younger. "They [the babies] keep us young," Benette said.

Originally, the pair took in newborns from a home for unwed mothers. But when those mothers began keeping their babies, the Crains became state foster parents. Frequently acquiring their charges just days old, the couple keeps most children for about six months.

Missouri tries to reunite families, but only four of the Crains' 168 children have returned home. Relatives adopted a few. Strangers adopted the majority.

The Crains attend First Baptist Church, Raytown. They chose this fellowship for its mixture of races and its youth ministry. They wanted those benefits for their 14-year-old adopted daughter, Jenny, an African American.

They got Jenny, their first baby from the state, at 4 weeks old. Three years later, her mother asked the Crains to adopt her. By then in their 60s, they knew Social Services didn't approve of interracial adoptions. Still, they prayed that if God wanted them to have Jenny, the adoption would be problem-free. It was.

Missouri approves senior adoptions if prospective parents pass a physical, prepare a will and have arranged backup caregivers in case both become unable to care for the child. The Crains' two married daughters agreed to be their backup.

Jenny helps with the babies, too. She breezed in from school, scooped up the infant at Howard's feet and disappeared with him into her room. Minutes later she reappeared. "He's asleep," she said. "I put him in his crib."

How do the Crains handle losing their babies? "We cry a lot," Benette said. "For some babies it's harder than others. We've had some up to two years."

Being involved in choosing the adoptive parents helps. "Since we're Christians, we always pray about it. We look for different things in parents than the state does," they explained.

The Crains have kept track of most of their charges. "This year we got four high school and two college graduation announcements and one wedding invitation from our babies," Benette said.

"We get a lot of pictures at Christmas. It's very rewarding to see them grow up and be successful."

The Crains plan to continue caring for babies for another two years. Then they'd like to take adoption agency placements.

"They place their babies very quickly, so most would stay about two weeks. Even though we're older, we've got a lot to give. We can still get around. We can still take care of babies, and we still want to," Benette said.

Would they do it over again? Howard nodded as he gently rocked his little charge to sleep.

Benette replied, "Yes. Only we'd start a lot sooner." (02-21-06)