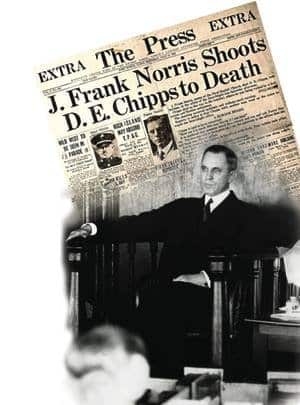

FAIRFAX, Va.—When the pastor of one of the nation’s largest churches shot and killed an unarmed man who entered his study threatening him, the whole nation took notice.

|

J. Frank Norris, the controversial pastor of First Baptist Church in Fort Worth who earlier had been indicted but acquitted on arson and perjury charges after his church burned, stood trial for first-degree capital murder—and beat the rap.

The courtroom drama drew page-one attention in newspapers across the country in the mid-1920s. But today, more people know Norris for his part in denominational schisms than for his role as defendant in a high-profile murder trial.

Nearly 40 years ago, David Stokes first heard about how Norris shot and killed D.E. Chipps, a wealthy Fort Worth lumberman and close friend of Mayor Henry Clay Meacham—whom Norris defamed both in the pulpit and in print. Stokes found the story captivating, and he began to collect material related to the event.

“It had all the elements of a powerful drama,” he said.

Four years ago, Stokes decided the story was too compelling to remain untold, and he started conducting serious research with the intention of writing about it.

Stokes’ book about the Norris murder trial, The Shooting Salvationist, first appeared as a privately published work under the title, Apparent Danger. Steerforth Press subsequently picked up and revised the book, and it will be released July 12—the 85th anniversary of the day Norris shot Chipps.

“Any time there is a scandal involving a clergyman, it’s an ugly thing. But who better to tell the story than someone with an inside view?” Stokes reasoned.

After all, his mother “was converted under the preaching of J. Frank Norris” at Temple Baptist Church in Detroit, Mich., although she later grew quite critical of him. Stokes grew up an independent fundamentalist Baptist and attended Baptist Bible College in Springfield, Mo., a school that grew from an offshoot of the movement Norris led.

Today, Stokes serves as pastor of Fair Oaks Church in Fairfax, Va., a nondenominational congregation in the suburban Washington, D.C., area.

Stokes sees the Norris/ Chipps affair as an example of overreaction by Norris and overreaching by the prosecutors. He believes Norris probably did not act in with premeditation to kill Chipps, but he responded in fear at the possibility of being physically assaulted by the burly lumberman, who had been drinking.

Attorney W.P. “Wild Bill” McLean and the other members of the high-powered legal team assembled to prosecute the case probably could have won if they had charged Norris with second-degree murder or man-slaughter, but they became “blinded by hatred of Norris,” Stokes said.

“I think the jury fumbled the ball, but more than that, I think the prosecution fumbled it by insisting on a verdict of first-degree murder or nothing,” he said.

While The Shooting Salvationist contains all the elements of a true crime novel, Stokes sees it more an a character study of a “Lyndon Johnson-style larger-than-life” figure whose tremendous gifts and flagrant flaws continue to shape a significant segment of conservative Christianity in the United States.

“The DNA of Norris still is seen in the whole independent Baptist and fundamentalist movement,” he said.

Norris exercised authoritarian leadership utilizing “coercion, control and manipulation … and that continues to happen,” Stokes noted. “Norris was undoubtedly a person of great gifts and abilities, but he also operated out of dysfunction.”

To a large degree, the feuds Norris launched that affected the lives of many people—whether in local politics or denominations—grew out of “petty slights, hurt feelings and personality conflicts,” he added.

“But Norris was not as doctrinaire as people think he was. He was a pretty pragmatic, populist guy,” Stokes observed.

For instance, Norris built alliances with the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s primarily because they shared his fervent anti-Catholic views. But by the early 1950s, he embraced Catholics as comrades in the fight against “godless communism.”

“Norris always needed a bogeyman. He always needed an enemy,” Stokes said. And when it came to defeating an opponent, “Norris believed the end justifies the means.”

Perhaps the greatest lesson to learn from Norris’ life centers on his ability to build a church and a movement around his own powerful personality.

“There’s a lesson concerning the danger of any cult of personality—the worship of a person,” Stokes said. “And that transcends categories of politics, religion and entertainment.”