(RNS) By calendrical coincidence, we have two national celebrations this Jan. 16.

One is the birthday of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., one of the best-known and honored figures of the 20th century.

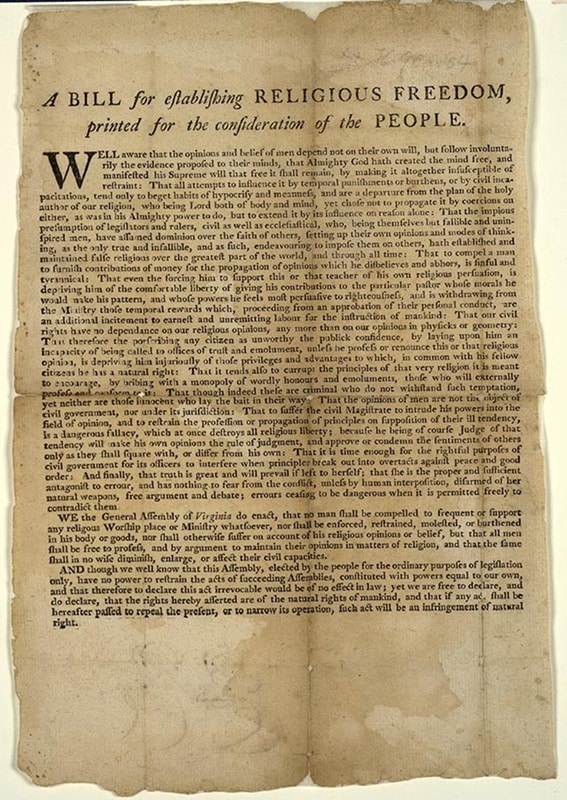

The Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom. (Image courtesy of Creative Commons)The other is the birth of religious freedom in America – celebrated as Religious Freedom Day, which by an act of Congress commemorates the 18th-century enactment of the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom. The day is recognized in an annual proclamation by the president and is highlighted by a variety of religious, educational and civil rights groups around the country.

The Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom. (Image courtesy of Creative Commons)The other is the birth of religious freedom in America – celebrated as Religious Freedom Day, which by an act of Congress commemorates the 18th-century enactment of the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom. The day is recognized in an annual proclamation by the president and is highlighted by a variety of religious, educational and civil rights groups around the country.

Since religious freedom has become one of the central issues of our time, was featured in the presidential campaign of Donald Trump and will very likely be part of the debate in the next Congress and beyond, this is an opportune moment for us to reflect on the meaning of religious freedom in our history.

First, let’s note that religious freedom is the source of the other freedoms guaranteed by the Constitution and the First Amendment.

Free speech and a free press – and just about everything else – would not be possible without this right to think freely, to believe as we will, and to change our minds free from the undue influence of government or powerful religious institutions.

Indeed, this right to believe differently from the rich and the powerful allows for the possibility of social change, and as King knew, even to see the promised land of freedom and justice for all.

The Virginia Statute, authored by Thomas Jefferson in 1777 and shepherded through the Legislature by James Madison in 1786, made the state the first in history to ensure complete religious freedom and equality. The statute is widely regarded as the foundation for how the framers of the Constitution (and later the First Amendment) approached matters of religion and government.

The statute’s declaration that citizens may believe as they will and that this “shall in no wise diminish, enlarge, or affect their civil capacities” adds further clarity to the intentions of Jefferson and his allies in creating founding documents that are rooted in religious freedom and separation of church and state.

Jefferson understood the historic significance of this breakthrough for liberty and asked that he be remembered on his tombstone for just three things in his remarkable life: authoring the Virginia Statute, the Declaration of Independence and the founding of the University of Virginia.

Religious freedom was one of the signature accomplishments of the American Revolution. Throughout the Colonial era, the Anglican Church in Virginia had brutally suppressed religious minorities, notably Baptists and Presbyterians. The statute made religious equality the new standard of justice.

Still, the principle entered our culture and laws only in fits and starts. It’s fair to say we are still working on it. And of course, freedom of religion in the era of the Founding Fathers did not mean freedom for all and in all respects, as African and Native American slaves, women and people who were not landowners could attest.

Nor did the principle eliminate religious prejudice and discrimination. But what it did do was facilitate every struggle for advances in human and civil rights ever since.

King understood this. In his 1963 Letter from a Birmingham Jail, he acknowledged the source of his movement in “the Negro church.” He wrote, for example, that the students who staged sit-ins in a campaign to desegregate lunch counters in the South were “standing up for the best in the American dream and the most sacred values in our Judeo-Christian heritage.”

Five years later, in his last sermon, delivered just hours before his death, he again recalled how the lunch counter sit-ins took “the whole nation back to those great wells of democracy which were dug deep by the Founding Fathers…”

“We know through painful experience,” King wrote in his Birmingham letter, “that freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor. It must be demanded by the oppressed.”

This Jan. 16, let’s consider the legacies of both King and the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom together in the bright light of our history.

(Frederick Clarkson is senior fellow for religious freedom at Political Research Associates and author of “Eternal Hostility: The Struggle Between Theocracy and Democracy”)