Jennifer Marshall (left), with the Heritage Foundation, and Summer Ingram, with the Congressional Prayer Caucus Foundation, who said they support “traditional marriage” hold balloons that says “protect religious liberty” outside of the Supreme Court Friday June 26, 2015, in Washington. (AP Photo/Jacquelyn Martin)(RNS) — As the summer heat waxes and state legislative sessions wane, the Congressional Prayer Caucus Foundation has scored a few small but significant victories.

Jennifer Marshall (left), with the Heritage Foundation, and Summer Ingram, with the Congressional Prayer Caucus Foundation, who said they support “traditional marriage” hold balloons that says “protect religious liberty” outside of the Supreme Court Friday June 26, 2015, in Washington. (AP Photo/Jacquelyn Martin)(RNS) — As the summer heat waxes and state legislative sessions wane, the Congressional Prayer Caucus Foundation has scored a few small but significant victories.

This year, five state legislatures passed laws mandating that every public school prominently display the U.S. motto, “In God We Trust.” The addition of Arkansas, which passed such a law in 2017, brings to six the number of states with public school mandates, including Alabama, Florida, Arizona, Louisiana and Tennessee.

Those laws, mostly sponsored by legislative prayer caucuses in about 30 states, were inspired by the foundation’s 2017 manual known as Project Blitz, a 116-page guide for state legislators listing 20 model bills of which “In God We Trust” is the first.

For a foundation begun in late 2005 as an offshoot of the Congressional Prayer Caucus, that’s an impressive start.

The list of “In God We Trust” legislation doesn’t count states like Minnesota that passed a law allowing but not mandating that public schools post the motto, or a new North Carolina law requiring the Department of Motor Vehicles to issue optional “In God We Trust” license plates.

Project Blitz has been likened to the American Legislative Exchange Council, or ALEC, which brings conservative state lawmakers together with corporate sponsors to draft model legislation. The model bill project was conceived by the foundation based in Chesapeake, Va., alongside two partners: WallBuilders, the group headed by Christian nationalist David Barton, and the National Legal Foundation, a Christian public interest law firm.

The project is intended to protect religious liberty, which the foundation says is a key American principle that has “weakened and come under increasing attack.”

But the way Project Blitz defines religious freedom is misleading, said Frederick Clarkson, senior research analyst with Political Research Associates, a social justice think tank based in Somerville, Mass.

“Religious freedom in the sense that Project Blitz means it is not what the rest of us understand as the revolutionary aspiration of religious equality for all,” Clarkson said. “It’s more of a cover for some conservative Christians to promote their religious and political views via public policy and public institutions, and as a justification for broad exemptions from the law.”

In addition to the “In God We Trust” model bill for public schools, the Project Blitz manual offers a raft of other bills, including:

- A Religion in Legal History Act that endorses an “appropriate presentation of the role of religion in the constitutional history of the United States” to be placed in courthouses and other public institutions (Oklahoma Gov. Mary Fallin signed such a law in May);

- A state resolution on marriage that says the state “supports and encourages marriage between one man and one woman”;

- A Child Protection Act that allows religious exemptions for adoption and foster care agencies from serving same-sex couples (both Kansas and Oklahoma passed such laws this year);

- A Licensed Professional Civil Rights Act that would exempt “pharmacists, medical personnel and mental health practitioners from providing care to LGBTQ people, and such matters as abortion and contraception”;

- A Student Prayer Certification Act that would require states to certify that they are not preventing students from engaging in constitutionally protected prayer.”

Repeated email and phone calls to the foundation were not returned.

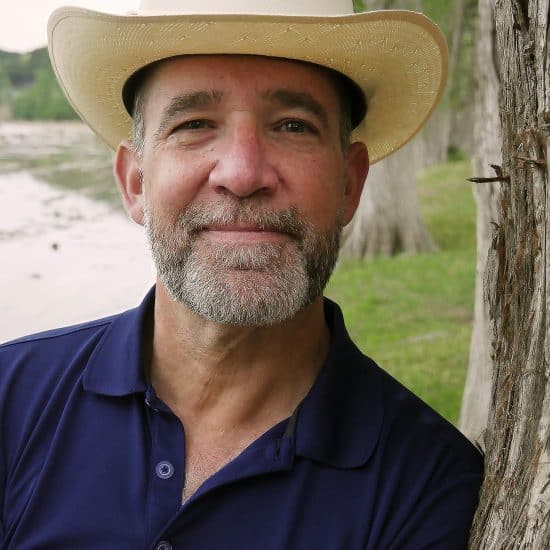

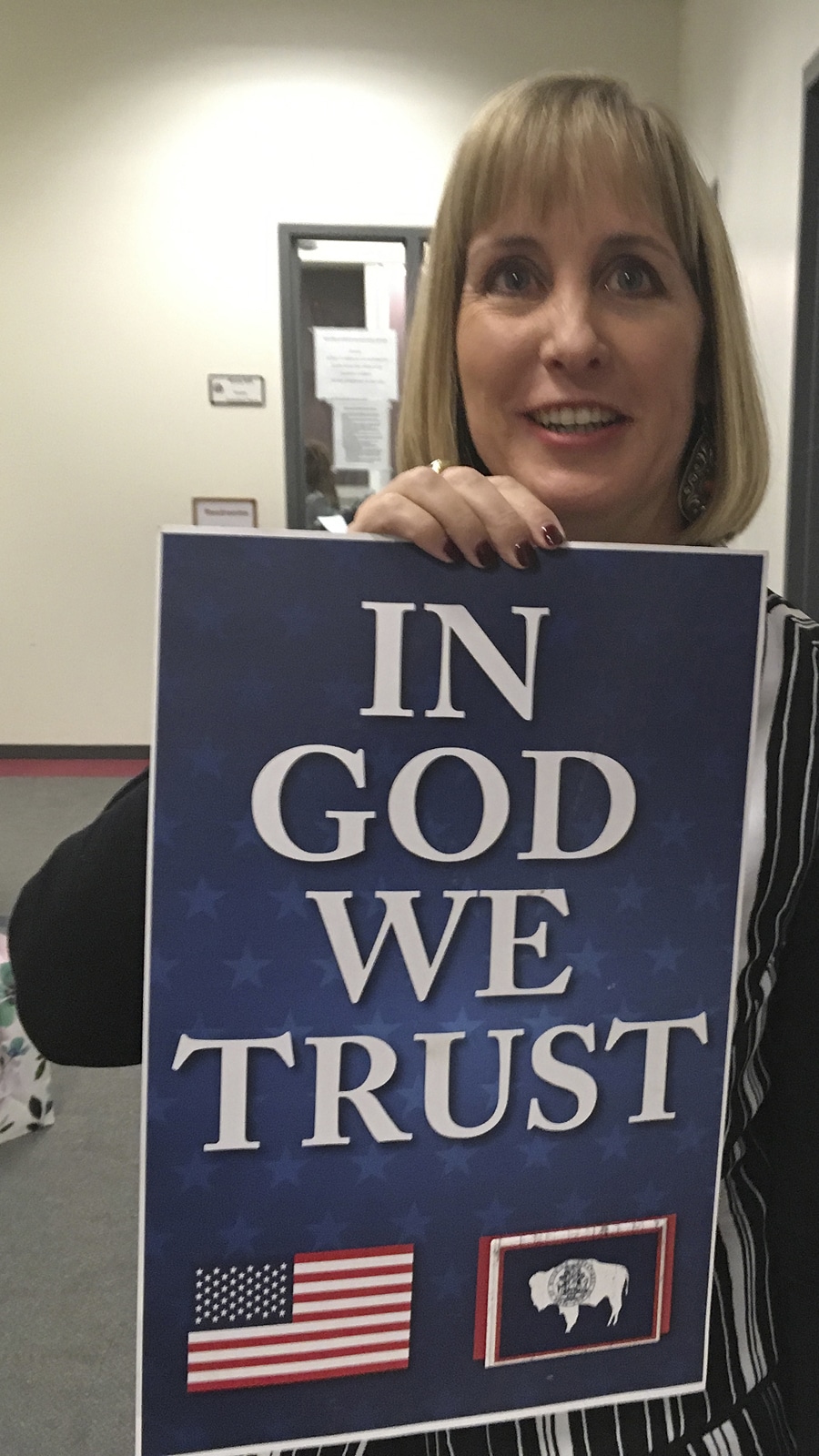

Wyoming State Rep. Cheri Steinmetz,R-Lingle, on March 6, 2018, shows an example of an “In God We Trust” placard in Cheyenne, Wyo. Steinmetz sponsored a bill that would allow people to donate such placards for display in prominent places in state buildings and schools. The measure died in the state Senate. (AP Photo by Bob Moen)Americans United for Separation of Church and State has been keeping track of Project Blitz legislation. It found that there were 76 bills introduced in state legislatures nationwide in 2018 that were either identical or used similar language to the Project Blitz manual.

Wyoming State Rep. Cheri Steinmetz,R-Lingle, on March 6, 2018, shows an example of an “In God We Trust” placard in Cheyenne, Wyo. Steinmetz sponsored a bill that would allow people to donate such placards for display in prominent places in state buildings and schools. The measure died in the state Senate. (AP Photo by Bob Moen)Americans United for Separation of Church and State has been keeping track of Project Blitz legislation. It found that there were 76 bills introduced in state legislatures nationwide in 2018 that were either identical or used similar language to the Project Blitz manual.

Many legislators said they saw no harm in “In God We Trust” measures.

“Our national motto and founding documents are the cornerstone of freedom and we should teach our children about these things,” said Tennessee State Rep. Susan Lynn, who sponsored the bill that passed in that state in March.

Project Blitz writers acknowledge that “In God We Trust” bills may seem symbolic, but they serve a larger purpose, which is to lay the foundation for future efforts. “Despite arguments that this type of legislation is not needed, measures such as the ‘In God We Trust’ bill can have enormous impact,” reads the manual. “Even if it does not become law, it can still provide the basis to shore up later support for other governmental entities to support religious displays.”

Some religious groups have begun to push back. In North Carolina, where an “In God We Trust” bill passed in the state House in June but stalled in the state Senate, the executive director of the North Carolina Council of Churches went on record opposing such a bill.

“For those who have no religious tradition, whose beliefs also are protected by the First Amendment, the motto is an affront,” wrote Jennifer Copeland in a blog post. “For those who DO believe the tenets of Trinitarian Christianity, we don’t need a sign at school telling us who we trust.”

Other liberal Christians are also objecting to efforts to use religious freedom as a ruse.

Last month, the Presbyterian Church (USA) passed by consensus a resolution at its General Assembly that said it will “stand against any invocation of ‘religious freedom’ (in the public sphere) that deprives people of their civil and human rights to equal protection under the law, or that uses ‘religious freedom’ to justify exclusion and discrimination.”

Regional affiliates of Americans United — including one in North Carolina — are watching developments closely.

“They’re destroying the integrity of religion in America,” said Rollin Russell, a retired United Church of Christ minister active with the Orange-Durham chapter of Americans United in North Carolina, referring to the prayer caucus groups. “It makes me crazy that people with that understanding of Christianity are enforcing their theological perspective on everybody else.”