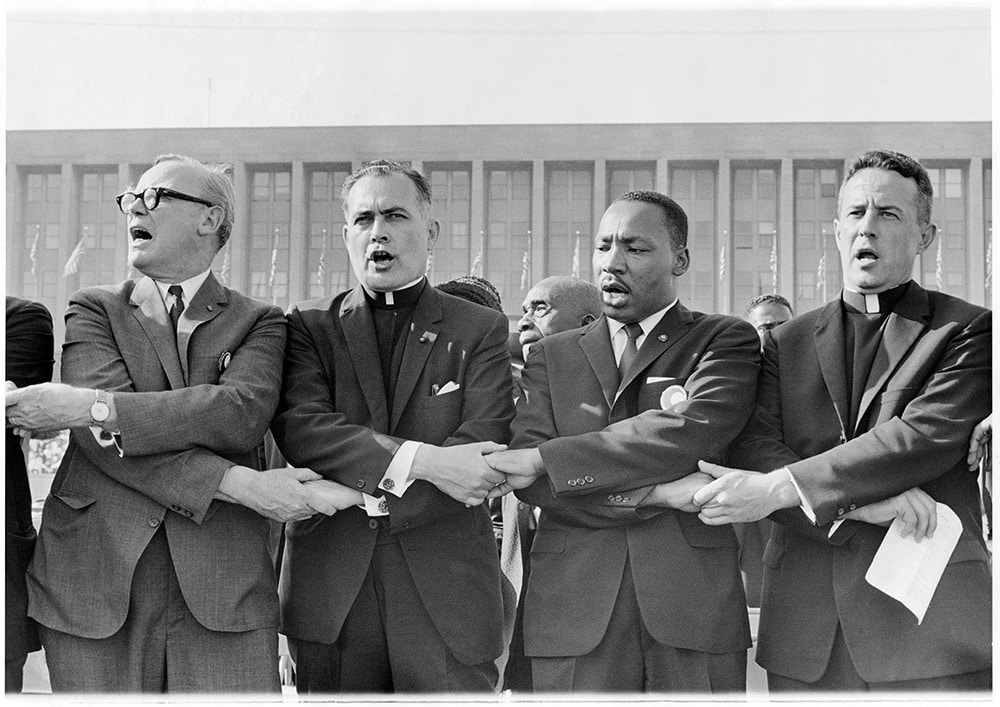

Rev. Theodore Hesburgh, center left, holds hands with Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., while singing “We Shall Overcome” during a civil rights rally at Soldier Field in Chicago on June 21, 1964. Photo courtesy of OCP Media

(RNS) — In the media and in our popular imagination, the religious right towers over our political landscape. So much so, in fact, that one could be forgiven for thinking that reflexive Republicanism is the only widespread expression of Christianity in politics.

The religious right’s shadow is so large that it is usually the reference point for any discussion of the religious left. Each election cycle, a spate of articles, essays and columns, mostly by white journalists, appears, inquiring why the religious left is not as important as the religious right. Is there a religious left at all?

After their party largely neglected faith outreach in 2016, the 2020 Democratic presidential candidates seem to have caught the religion bug, and to hear them talk some might think the religious left has a chance this cycle to counter the religious right’s decades-long hold on American politics.

The truth is that both religious camps are more likely to follow than lead when it comes to who determines the two parties’ policies.

Sen. Cory Booker, D-N.J., speaks to the Festival of Homiletics on May 22, 2018, at Metropolitan AME Church in Washington. RNS photo by Jack Jenkins

For all its power to move voters to the ballot box, the religious right has an agenda that’s unpopular even with many of its supposed constituents and has floundered when it comes to making legislation or overturning legal precedents.

And in spite of the Democratic Party’s great diversity and depth of religious belief, its leaders’ core commitment to pluralism and a secular state keeps them from adopting the language of faith in compelling ways.

Once upon a time, it might have been said that the religious left led the Democratic Party to new positions and priorities. From the Progressive Era to the civil rights era, it was common to see clergy — white, black, Jewish, Protestant, Catholic — constructing intellectual and theological arguments from the pulpit and marching on the front lines. The people in the pews were the rank and file of these movements.

Today, while the religious left may support the Democrats’ new vanguard of democratic socialism, it would be difficult to claim that faith has been the inspiration, much less provided the activists on the ground.

But the Democrats have a deeper disconnect with their religious wing: Many believers who are otherwise staunchly on the Democratic side are evolving too slowly, or not at all, on the politics of sexual liberation. Too many have not abandoned a belief that the unborn deserve protection, that marriage is between a man and a woman and that there are two genders, biologically determined at birth.

Hispanics, and to a lesser degree blacks, support legal abortion at lower levels than whites. And while white-dominated mainline Protestant denominations have supported abortion rights and now same-sex marriage, black church traditions have remained more traditional.

In the Democratic coalition, these beliefs are held to be not merely wrong but bigoted. They are barely tolerable in Muslims and other religious minorities, but they are completely inexcusable for white Christians.

Crucially, this includes white Catholics, who should support a religious left agenda on immigration and poverty relief, but may be influenced by their church’s unfashionable beliefs about abortion, gender and sexuality.

So while many faithful progressive Christians and other religious minorities support abortion rights and LGBT equality, overall the religious left’s voice is uneven and relatively soft.

President Trump attends the Liberty University Commencement Ceremony and delivers remarks on May 13, 2017, Lynchburg, Virginia. Jerry Falwell Jr. is at right. (Official White House Photo by Shealah Craighead)

On the Republican side, the faith community has no problem finding its voice — the religious right established itself with a remarkably unified chorus broadcast on radio and television. The right’s difficulty is that this voice has grown hollow as it gives religious sanction to an agenda that prioritizes the rich over the vulnerable.

But after decades of acculturation, conservative Christianity has become so intertwined with Republican politics that even the rise of the “Tea Party” movement in 2010, which introduced anti-government and even racist elements, did not strain the GOP-evangelical marriage. Even Trumpism, which might have tested the religious right’s long insistence that character mattered, hasn’t dissuaded conservative Christians from supporting the current president the same way they have every Republican president since Ronald Reagan.

Even among the Trump-weary, conservative white Christianity’s path seems clear enough: Furrow their brows at Trump’s most obnoxious and authoritarian behaviors until he is out of office, at which time the conservative-Republican alliance can continue as though Trump never even happened.

That orthodoxy has recently begun to be challenged. Last month, National Review writer David French called out Franklin Graham for supporting Trump after having insisted during Bill Clinton’s presidency that bad character disqualified a leader from receiving Christians’ support.

When the American Family Association, a right-wing mailing list marginally relevant in the nuttier precincts of the religious right, took French to task for his article, French punched back with a show of backbone that contrasted with the rest of so-called Never Trump white evangelicalism.

Sadly, it would be more idealistic than I am to expect other Christians in the GOP to adopt French’s critique. Activists, operatives and observers have long assumed that religion is a fixed social identity and that political ideology and voting behavior flow from values that faith commitments endue. But social science research has shown persuasively that the causal arrow points the other way: It could be the case that partisanship is the foundational social identity, and citizens accommodate their religious beliefs and practices to their ideology.

But the fact is the parties and the country would be stronger if our religious constituencies did push for their values within their political coalitions. Without some pushback against Trump’s realpolitik and his character there is nothing distinctively religious about conservative Christians’ support of the GOP at all. They would all be Republicans anyway. Similarly, Democrats whose faith prompts them to defend the unborn and respect marriage should loudly push to be heard, and should consider making their votes dependent on concessions to their views.

Otherwise, these believers are simply Republicans and Democrats, giving theological justification for preferred policies and attempting to frame party voting as a matter of religious devotion. This, of course, suits both parties just fine.