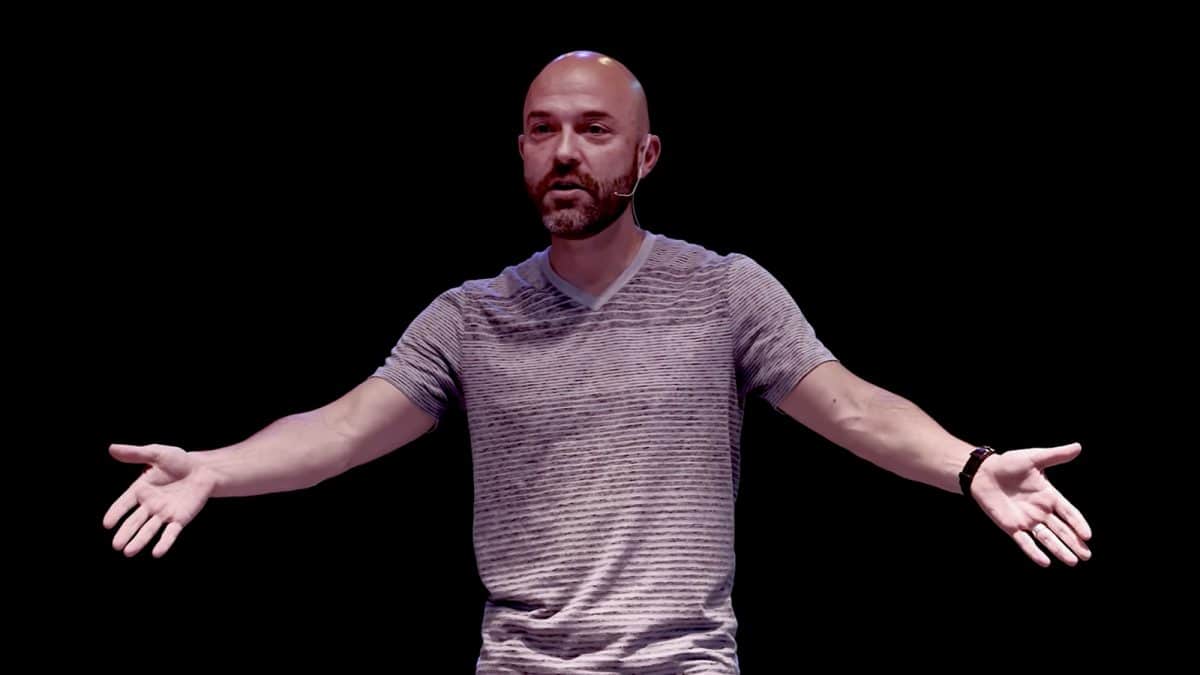

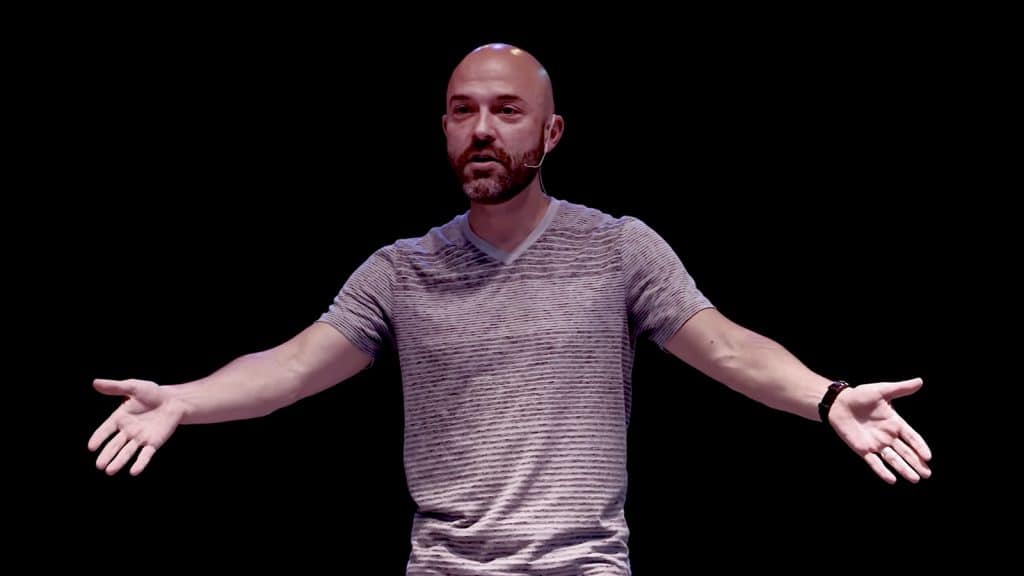

Joshua Harris delivers a TEDx Talk in 2017. Video screenshot

(RNS) — In the photo accompanying the announcement of his “massive shift in regard to my faith in Jesus,” posted on Instagram in late July, Christian pastor Joshua Harris stands at the edge of aquamarine waters, resolutely looking ahead.

In the caption, the author of the hugely influential 1997 book “I Kissed Dating Goodbye” told his followers, “The popular phrase for this is ‘deconstruction,’ the biblical phrase is ‘falling away.’”

“By all the measurements that I have for defining a Christian, I am not a Christian.”

When, weeks later, Marty Sampson of the popular Christian music group Hillsong Worship, posted a similar statement on the popular social media platform, saying he is “genuinely losing my faith,” apostasy suddenly seemed to be, well, trending.

Deconstructing or denouncing one’s faith isn’t new, pointed out pastor-turned-secular humanist speaker and author Bart Campolo.

“What’s new is that they’re doing it on social media, and so the response that they’re getting and the way it’s being spread around is very different,” he said.

Many of those responses have come from other Christians.

That includes John Cooper of the Christian metal band Skillet, who followed Harris and Sampson with his own Instagram post, asking, “What in God’s name is happening in Christianity?”

“More and more of our outspoken leaders or influencers who were once ‘faces’ of the faith are falling away. And at the same time they are being very vocal and bold about it,” wrote Cooper, who, along with sleeve tattoos and a footlong wedge of beard, has the bearing of an evangelical senior statesman.

The fact that a former Christian “influencer” would continue to want to influence followers even after leaving the faith is “sad and depressing and even upsetting,” he added.

Adult influencers “should know that social media is not your diary,” the musician told Religion News Service, saying it can be confusing and even hurtful to those followers who look to influencers for guidance.

“If you are a leader and you have been leading people in the faith for 20 years, you don’t throw that out on the Internet,” he said.

Cooper also worries about the influence Christians give to “worship leaders and Christian thought leaders,” he said.

“Let’s just face it, some of this is all of our faults, because as Christians we have more of an appetite for entertainment than we do for what I would call pressing into God.”

Have we seen many African American Christian leaders publicly denounce their faith? I know we’ve seen some fall into sin and lose ministries, but I’m curious if you’ve seen this. I have not but I could be mistaken…

— Trillia Newbell (@trillianewbell) August 14, 2019

Trillia Newbell, author and director of community outreach for the Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission for the Southern Baptist Convention, also responded on social media to both Harris’ and Sampson’s announcements.

Newbell, too, was disappointed that both leaders chose to make statements publicly. What’s more, she said, their statements didn’t seem to be questioning, but rather proud, telling people not to feel bad for them.

In his post, Harris said he doesn’t “view this moment negatively”; Sampson assured followers he is “so happy now, so at peace with the world.”

Newbell stressed that she feels sorrow and compassion for them.

“I don’t know what they are experiencing or what they’re going through. And I just think if they are God’s, if they truly are his, they’re gonna come back — like you cannot outrun the Lord,” she said.

But deconstructing one’s faith doesn’t always mean denouncing it.

Sampson later deleted his Instagram post and clarified in comments elsewhere on social media that he hasn’t “renounced” his faith, but rather — despite his professed equanimity — admitted that “it’s on incredibly shaky ground.”

That kind of doubt and deconstruction is a natural part of faith, according to Brian McLaren, whose upcoming books include titles such as “Faith After Doubt” and “Do I Stay Christian?”

“In order to believe anything, you have to doubt something,” McLaren said.

McLaren went through his own deconstruction process after growing up in a conservative Christian environment, he said. He’s come out in a different place, with some different beliefs than he once had, but still considers himself a committed Christian.

He said he’s happy people are questioning conventional notions of God, especially when their beliefs entangled Christianity with white supremacy or the so-called “purity culture” of the 1990s that Harris’ book helped to popularize.

“What shocks me is that people are more upset by a Joshua Harris than they are by a Jerry Falwell, Jr., a Franklin Graham or Robert Jeffress who still say they believe in God, but the values that they espouse seem so cruel and heartless and critical. One of the ironies is the selective outrage,” he said.

McLaren also is glad Harris and Sampson have been open about their faith shifts.

And he pointed out they aren’t the first: Martin Luther’s doubts led to the Protestant Reformation. More recently, Michael Gungor and “Science Mike” McHargue of The Liturgists also have “come to a different kind of faith.”

The late progressive Christian author Rachel Held Evans also was “very open and courageous about her doubt,” helping many readers who came out of conservative evangelical Christianity, he said.

“I don’t think we’re going to get to a better place until more people will openly admit that the version of God and Christianity and religion that they inherited isn’t really acceptable or they can’t be honest and continue to hold it,” McLaren said.

Campolo, a former pastor and founder of urban ministry program Mission Year, is one leader who went through that deconstruction and came out no longer a Christian.

Like Cooper and Newbell, he expressed concerns about public proclamations about one’s deconversion.

When he left Christianity years ago for secular humanism, he discussed it with friends and family, including his dad, influential pastor Tony Campolo. Word spread slowly, and he didn’t discuss it publicly until years later when, he laughed, somebody noticed he had become the humanist chaplain at the University of Southern California.

But now spiritual lives are lived online, Campolo said.

That comes with an instantaneous response to any shifts leaders announce before they might have counted the huge cost of leaving their faith. And some who walk away end up returning, either because they put the pieces of their faith back together or because they miss being part of the culture and community within Christianity.

“What’s weird is when you do your spiritual life as performance, then even when you come to the end of it, you may stay with your audience,” Campolo said.

“But it’s a whole different ball game when you deconvert, because people are really, really generous, and they’re really OK with lots of doubt and lots of confusion all the way up to that line. When you cross that line, it’s terrifying for the people who have in a sense identified with you.”

(Post can no longer can be viewed on Instagram)

A post shared by Marty Sampson (@martysamps) on Aug 30, 2019 at 8:17am PDT

Harris has declined interviews, and Sampson could not be reached by Religion News Service.

But both have continued to post on Instagram.

In a post Friday (Aug. 30) accompanied by a photo and quote from boxer Muhammad Ali, Sampson said he’s free from fear and pain and what other people think of him — and he’s looking for Jesus, even if he’s not sure he will find him.

“I will search for you Jesus. I’m wide open,” he said. “My journey begins.”