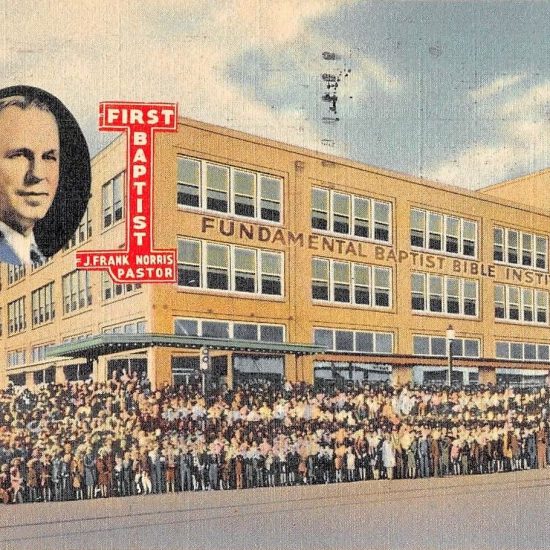

Chaldeans and other protesters demonstrate in June 2017 outside the U.S. Courthouse in Detroit as a federal District Court judge decided the fate of 114 Iraqi immigrants facing deportation. Photo: Weam Namou

STERLING HEIGHTS, Mich. (RNS) — Jimmy Al-Daoud’s body arrived from Iraq on Friday (Aug. 30) in a casket, sent back to Michigan so he can be buried next to his mother. Born in a refugee camp in Greece in 1978, Al-Daoud was granted refugee status, along with his family, in the United States in 1979. They traveled from Greece to Detroit when he was less than a year old. Al-Daoud, who suffered from bipolar schizophrenia and diabetes, was deported to Iraq in July 2019. He died a few months later on the streets of Baghdad, at age 41, when he couldn’t find medication.

Al-Daoud’s deportation and death is not a mystery or a mistake. It’s part of a progression that has tightened a cordon around the Chaldean Christian community for more than five years.

On a hot Sunday afternoon in 2014, I covered a protest for The Chaldean News in Sterling Heights, nicknamed “Little Baghdad” for its Iraqi immigrant population, most Chaldean Christians. To get to the scene, I only had to round the corner at the end of my street. My children kept up alongside on their scooters.

As soon as we stepped onto Ryan Road, a main road that connects Sterling Heights to Detroit, we saw American, Iraqi, Chaldean and Assyrian flags fluttering. Protesters wore T-shirts with the words “Stop Killing Iraqi Christians” in red or else T-shirts marked with a red Arabic “N” — the letter, standing for “Nazarene,” with which the Islamic State marked the homes of Chaldean Christians in the villages of Iraq.

Signs and banners depicted pictures of murdered children and demanded that the U.S. government end the anti-Christian genocide in Iraq.

Three years later, on another hot summer afternoon, I was on Ryan Road covering another protest, after U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement officials had raided homes and even a hospital, arresting more than 100 Iraqi nationals, mostly Chaldeans, in the Detroit area. Many of the friends and family members who had been detained had followed their loved ones to the ICE field offices in Detroit.

After the detainees were escorted out of the building and onto three buses, several people jumped in front of the moving vehicles. One woman, overcome with fear for her husband, fainted. Another came away with bruises on her arm from the police restraining her, because she refused to let her brother go “just like this.”

The detained had not entered the United States illegally. Most had lost their green card status for having at some point broken the law and therefore were under an order of deportation. Most of their cases were low-level, nonviolent crimes committed decades ago, often a marijuana possession charge that was once a felony and today is a misdemeanor. Most had long since paid their debt to society and kept a clean record.

While my family has not been directly affected, a number of our friends and our children’s schoolmates were and some still are. In my children’s elementary school, students who had a loved one detained didn’t show up to class for days, or weeks.

They shared their fears on social media, sending private videos of their ordeals. A 12-year-old talked about the pain of seeing her father handcuffed in front of her and “ripped out of her life.” An elementary student talked about her brother, whose wedding was scheduled in a few weeks (she was going to be one of his bridesmaids). He had not committed a crime but had an “error” on his file. A woman, seven months pregnant, ended up in the hospital due to the stress of the situation.

Being deported to Iraq then, when ISIS still controlled much of the country, especially with the tattoo of the Christian cross on your wrist, was a death sentence.

People often talk about the Judeo-Christian faith in this country, and yet I’m baffled how so few people know that the indigenous people of ancient Mesopotamia were among the first to embrace Christianity. Up until 2003, and the beginning of the Iraq War, many people didn’t realize that Iraq is associated with Mesopotamia (many still don’t).

Mesopotamia was home to the Chaldeans, Sumerians, Babylonians, Assyrians and Akkadians. It is the setting for much of the Old Testament, including the Garden of Eden, Adam and Eve, and the prophet Abraham.

Some significant developments and inventions credited to the Mesopotamians include writing; the wheel; agriculture; astronomy; mathematics; separation of time into hours, minutes, and seconds; irrigation; religious rites; and beer. The first writer in recorded history was a woman from ancient Mesopotamia. Enheduanna, a princess, priestess and poet, wrote and taught about three centuries before the earliest Sanskrit texts, 2,000 years before Aristotle, and 1,700 before Confucius.

I myself grew up not knowing much about my ancient rich Chaldean heritage. In Baghdad, where I was born, schools didn’t teach about history that occurred before Islam some 1,400 years ago.

Having endured persecution under the Ottoman Empire and oppression in a war-torn land ruled by dictators, our people did not have the freedom or resources to keep their culture and heritage alive. They were, for instance, discouraged from speaking in public their mother tongue, Sureth, a form of Aramaic.

This is Jimmy Al-Daoud’s heritage and mine. Our people, like other people of minority faiths, need protection and revival, not condemnation and expulsion. Rather than portray communities like ours as interlopers, or enemies, we Americans need to learn about each other and understand who we are, where we’re at and how to change where we are going so that we don’t end up, similarly to Mesopotamia, becoming a hell on earth.

(Weam Namou is an Eric Hoffer Award-winning author of 13 books, as well as a filmmaker, journalist and poet. She is the founder of The Path of Consciousness, a spiritual and writing community, and Unique Voices in Films. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)