Last week, controversy erupted after news emerged about Alabama Republican Governor Kay Ivey, a member of a Southern Baptist church, performing in blackface while a student at Auburn University — during a skit at a Baptist Student Union party. Ivey quickly apologized, though she noted she did not remember the skit from 52 years ago. And the fact that she lost that memory from a Baptist gathering might perfectly capture the moral amnesia that continues to haunt our churches, conventions, and colleges.

Brian Kaylor

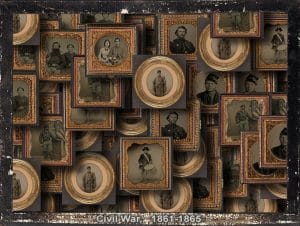

A mere generation ago, many white Baptists actively opposed the civil rights movement led by Baptist preacher Martin Luther King Jr. Two generations before that, many white Baptists actively supported the Confederacy and its cause of slavery. And in the generation between those, many white Baptists actively supported the ‘Lost Cause’ work of crafting pro-Confederate monuments and erecting Jim Crow laws.

But today, we’d like to act out a skit where we forget any of that occurred. And with that ignorance, comes the ability to support polices and practices that continue systemic racism. If, like Ivey, we can’t remember what our Baptist churches and institutions did in the past, how can we really improve things today?

Amazingly, Ivey is actually the second governor this year to face controversy over previously wearing blackface — which is more than the number of black governors! Virginia Democratic Governor Ralph Northam, a member of a historically-black Baptist church in the Progressive National Baptist Convention, faced calls to resign earlier this year after it was discovered that a yearbook on his page included a photo of one man in blackface and another in a KKK outfit. Like Ivey, Northam’s memory doesn’t include that moment. He said he didn’t remember the photo — or even which person he was — but admitted to wearing blackface on another occasion.

To her credit, Ivey didn’t try to deny the racist incident, accepting it occurred even though she can’t recall it. And she immediately offered her “heartfelt apologies for the pain and embarrassment this causes.” She also insisted it shows Alabama has “come a long way” since the 1960s even though “we still have a long way to go.” But if she doesn’t remember the past, does she really know how far we’ve come?

This cultural amnesia on the racism in our society and our churches holds back progress today. Flannery O’Connor tackled this idea in her short story “A Late Encounter with the Enemy.” In the story, a woman is excited to have her grandfather on stage in his Confederate uniform during her college graduation as a symbol of her family’s heritage.

This cultural amnesia on the racism in our society and our churches holds back progress today. Flannery O’Connor tackled this idea in her short story “A Late Encounter with the Enemy.” In the story, a woman is excited to have her grandfather on stage in his Confederate uniform during her college graduation as a symbol of her family’s heritage.

Yet, the 104-year-old grandfather “didn’t remember that war at all,” or his wife and kids. He plays the part of a general with a fake uniform, even though he was just a foot soldier. Living only in the present, he forgot the past and “didn’t have any use for history because he never expected to meet it again.” Barley alive, unable to walk, not sure where he is, and struggling to pay attention, the grandfather feels pain as he sits exposed in the sunlight during the ceremony.

A few words from the commencement speakers catch his attention, like “if we forget our past … we won’t remember our future and it will be as well for we won’t have one.” The words add to his discomfort.

As the ceremony drones on, the procession of black-robed graduates mixes in his imagination with the beckoning from the next life and his past memories of war and more. And as that enemy — the past — comes back, he dies on stage with no one recognizing it. His granddaughter mistakes his scared-to-death look with one of pride.

Through the tale, O’Connor suggests that the attempts of the “Lost Cause” to rewrite and even forget the past require costly self-deception. And the story notes how in our forgetfulness we can beam with pride over that we should find revolting.

If we don’t accurately remember our past, we take pride in things over which we shouldn’t gloat. Like Ivey, Northam, and the characters in O’Connor’s tale, we too often suffer from a rewritten or forgotten past. Many of our churches have whitewashed their histories to ignore the fact that early pastors and key leaders were slaveholders. Many of our colleges have forgotten their past to downplay their extensive ties to slavery.

Perhaps the recent blackface controversies could serve as a wake-up call to Baptists that we need to lead the way in dealing honestly with our past. After all, both governors embroiled in such scandals are Baptist — and one of the racist skits occurred at a Baptist event. If we won’t deal with our past, the country won’t be able to move forward. Let us not act — like that old Confederate grandfather — that all is well.

Brian Kaylor is editor and president of Word&Way.