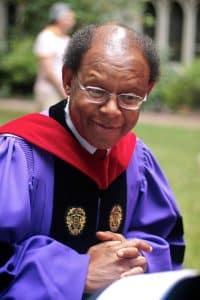

The Rev. James Cone, who died April 28, 2018, was known as the father of black liberation theology. Photo courtesy of Union Theological Seminary

(RNS) — A specter has been haunting white evangelicalism. It comes in the shape of James Cone, one of the founders of black liberation theology.

As last year ended, Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary President Daniel Akin tweeted in response to a (since deleted) tweet, “James Cone was a heretic & almost certainly not a Christian based on his teachings. … We do not legitimize him.”

After significant pushback, Akin made an amendment: “Though his writings & statements give me pause & great concern for his soul, if when I get to heaven I discover that James Cone is there, I will humbly, gladly & joyfully greet him as my brother in Christ as we together worship King Jesus for His amazing salvation, grace & love.”

Some other Christian thought leaders found this too generous. The Rev. Josh Buice, a Southern Baptist pastor, suggested that Akin had “normalized an enemy of the gospel.”

“Black Theology and Black Power” by James H. Cone. Image courtesy of Orbis Books

It’s not entirely clear what had occasioned this discussion of Cone, a longtime professor at Union Theological Seminary who died in 2018. But his sins against the white evangelical establishment date back to 1969, when he published “Black Theology and Black Power,” which interpreted the faith through the lens of the black freedom struggle.

In the book’s introduction Cone explained: “I wanted to speak on behalf of the voiceless black masses in the name of Jesus whose gospel I believed had been greatly distorted by the preaching and theology of white churches.”

His major themes include the idea, summarized in the mantra “God is black,” that God always sides with oppressed people, that the black experience is a legitimate source for doing theology and that the task of theology is liberation.

He raised questions about some tenets of faith that white evangelicals cherish, particularly the inerrancy of Scripture and the concept that Jesus died the death we deserved because of sin.

Perhaps the biggest problem white theologians have with Cone’s work is his emphasis on Jesus’ humanity over his divinity, and his conviction that salvation is as much about saving black people from the Klanner’s noose, or the officer’s chokehold, as it is about going to heaven when we die (if it has anything to do with the latter at all).

What Cone decidedly did not lack was sincere devotion to the way of Jesus as he understood it. No, the heresy Cone is guilty of is denying white Christian leaders’ authority to define what Christianity should look like for black people.

What constitutes heresy in the church depends on where the boundaries for orthodoxy (meaning “right belief”) are drawn. The Roman Catholic and the Eastern Orthodox churches excommunicated each other, in 1054, partly because of differing views on the nature of the Holy Spirit. Protestants were declared heretics by the Roman Catholics, and Protestants considered Catholics heretical, largely on the issue of papal authority.

Generally, white evangelicals claim Scripture as the sole standard for measuring orthodoxy. They don’t admit, or don’t see, the white frame that informs their theology.

Framing, something like a mental field of vision, determines what we don’t see and how we interpret what we do see. White people’s frame tends to ignore the systems of anti-black violence and white supremacy, both subtle and overt, that permeate American society.

This explains how some of the founders of American evangelicalism, George Whitefield and Jonathan Edwards, could emphasize God’s wrath and the need for repentance from sin while also owning slaves. They framed their reading of Scripture in such a way that it didn’t interfere with their white supremacy.

The Rev. James Cone at a Convocation of Union Theological Seminary in New York in 2009. Photo courtesy of Creative Commons

Today that kind of framing leads Whitefield’s and Edwards’ heirs to miss the connection between social action and Christian faithfulness. Mistaking their frame for the whole picture, they claim that what they can’t see isn’t there, and they dress their biases in religious language.

Cone recognized that black Christians needed to embrace a frame of their own. He said, rightfully, that black people and other persecuted groups don’t organize their faith around ruminating on theological propositions, but around encountering God in their struggle for freedom.

This experiential emphasis for knowing God can coexist with the white church’s emphasis on propositions, but Akin and Buice and similar thinkers can’t help but assert that their frame is better.

And that is how many a theology curriculum is organized, with white male theologians — Luther, Calvin, Barth — as required reading, and everyone else listed as extra credit (if that).

Cone was no more heretical than any white theologian celebrated today. White Christians simply don’t stop and frisk white theologians for doctrinal contraband as they do black thinkers.

Martin Luther, for example, slips through security with his anti-Semitic writings without seminary presidents expressing “concern for his soul.” Thinkers like Cone set off the alarm, on the other hand, because they dare to hold theologians like Luther accountable.

This racist exceptionalism is not restricted to Cone. At their recent Social Justice and The Gospel Conference, a panel of male Southern Baptist leaders who drafted a statement on social justice griped that more people didn’t raise issues about Martin Luther King Jr.’s theology, which also held that salvation had to do with social equity.

(They also raised the civil rights icon’s reported infidelities, but men in their position often manage to speak of Karl Barth without speaking of his mistress, Charlotte von Kirschbaum.)

Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary President Daniel Akin preaches in May 2019. Video screengrab via Southeastern Seminary

Even though both Cone and King rely heavily on Scripture and center their work on the person and work of Jesus every bit as much as white theologians do, the black thinkers are threatened with hellfire for not staying within the confines of white evangelicalism’s tiny gospel.

The difficulty men like Akin face in disposing of Cone or King is that white men no longer have ownership of hell. The days of handing heretics over to the state to be burned at the stake or drowned are long gone. Even excommunication only works if the “heretic” is accountable to a religious governing body. The threat of sanctions is the only thing that once made charges of heresy meaningful.

The internet’s democratizing influence makes even social excommunication — currently known as “being canceled” — useless. Remember when conservative heavyweight John Piper famously tweeted “Farewell, Rob Bell” when Bell’s 2011 book, “Love Wins,” questioned the existence of hell? Bell went on to publish a New York Times bestseller about the Bible, and there was nothing Piper could do about it.

This brings us back to questions of power and truth. Evangelical Christians have long expressed their deep concern about an immanent postmodern apocalypse that would annihilate the notion of “absolute truth.”

The advent of fake news in a post-truth presidential administration shows that their anxieties weren’t altogether unwarranted. But truth is not altogether gone. It’s just that we understand the difference between a landscape and someone’s field of vision — their frame.

Is the truth a landscape before us, which each of us sees only in part? Or is truth the power to force everyone to see the world through one frame?

Whiteness has often defined “truth” as the latter — the acceptance of a white supremacist, capitalist patriarchy as orthodoxy, as normal and ideal, with the threat of violence forcing compliance from those who suffer under that narrative.

By rejecting that one story, many marginalized people are simply stating that the white frame never fit us. It isn’t a loss of truth that’s at stake. It’s the white establishment’s loss of control over the frame, their power to define the boundaries of truth.

Cone is among those defiantly asserting that white people have no governing role over the religion of black Christians. He reminded us that the white evangelical frame for their gospel has nothing to do with meeting God in the black freedom struggle. He’s an example to us all. And there’s nothing white evangelicals can do about it.