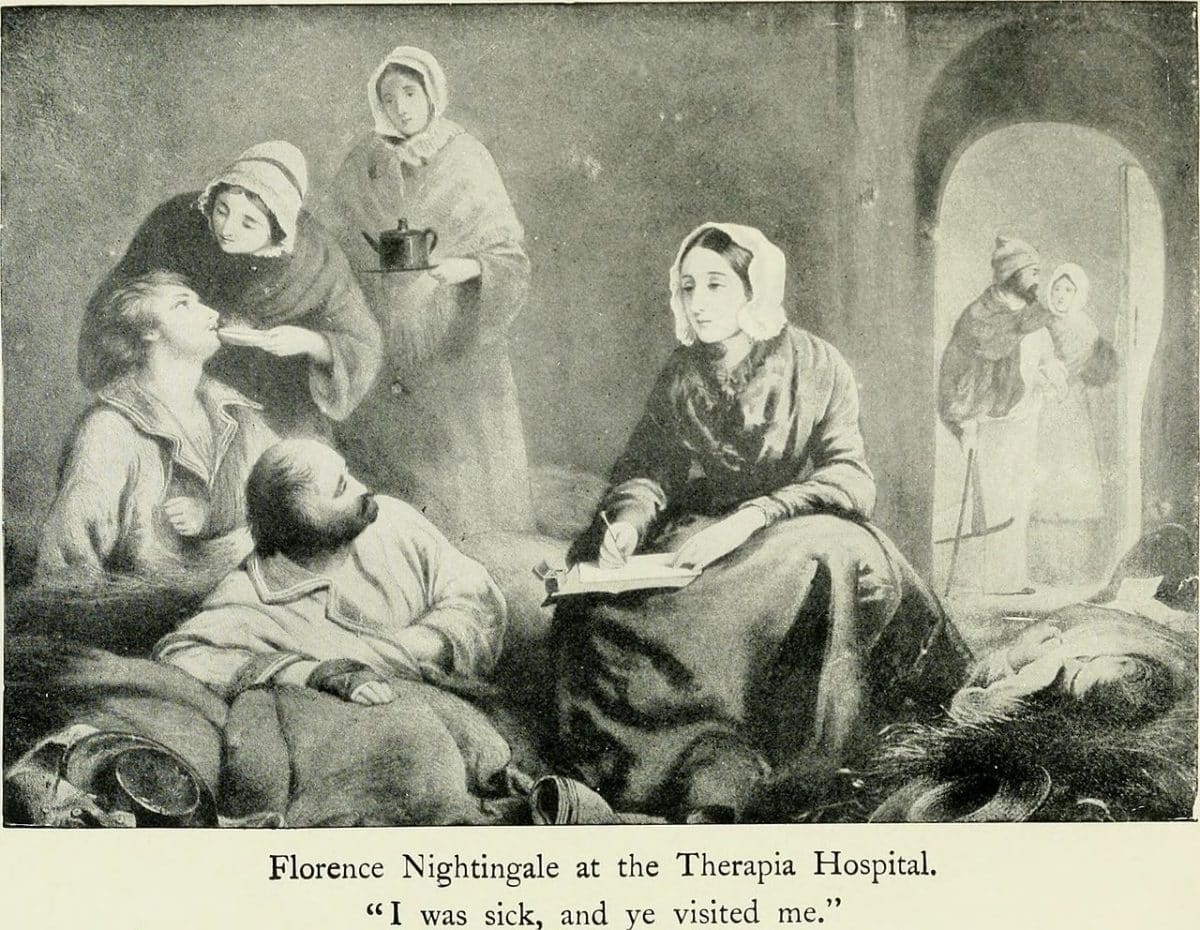

Florence Nightingale, from a 1913 biography (Wikimedia Commons)

The World Health Organization has designated 2020 as “Year of the Nurse,” marking 200 years since the birth of Florence Nightingale, who, along with Susan B. Anthony and Fanny Crosby were outstanding women born in 1820.

Leroy Seat

Learning about Florence Nightingale

In preparation for writing this article, I read Florence Nightingale the Angel of the Crimea, first published in 1909. The author of that old book is Laura E. Richards, whose mother was Julia Ward Howe, best known for writing “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.’

Howe was born less than a year before Florence Nightingale and died just over two months after Florence Nightingale death 110 years ago in August 1910. The two women knew each other to some degree.

According to Richards, it was her father, Samuel G. Howe, who in 1843 encouraged Florence to enter nursing at a time when, except for the Catholic Sisters of Charity, nurses in England “were for the most part coarse and ignorant women, often cruel, often intemperate” (p. 35).

Richards’s book, said to be “a story for young people,” was certainly a hagiographical account of Nightingale, but I much enjoyed reading it. Nearly three-fourths of the book is about Florence Nightingale’s meritorious work during the Crimean War (1854~56).

The Influence of Florence Nightingale

Nightingale felt God’s call to service of others in 1837 when she was 17 years old, and became a nursing student in 1844. After several years of courtship, in 1849 she declined a marriage proposal. Four years later she became the superintendent of the Institution for the Care of Sick Gentlewomen in London.

In the spring of 1854, Britain and France joined Turkey in opposition to Russia in what became known as the Crimean War. In the fall of that year, Nightingale went with a party of 38 nurses to work in a hospital in Scutari, Turkey, where thousands of injured soldiers were being cared for — and where a large percentage of them were dying.

When she and the other nurses arrived in Scutari, they were not welcomed. According to Richards, “the military authorities did not want female nurses,” because nurses at that time were “often drunken, generally unfeeling, and always ignorant” (p. 52).

But Nightingale began to implement significant changes. One of the patients there when she arrived wrote, “Everything changed for the better.”

According to “Nightingale in Scutari: Her Legacy Reexamined,” an essay about Nightingale’s legacy by Christopher and Gillian Gill, because of her work in Scutari and her subsequent teaching, Florence Nightingale “will forever be linked with modern nursing — and rightly so.”

The same essay states that three areas of contemporary medicine were “deeply influenced by her”: hospital infection control, hospital epidemiology, and hospice medicine.

Following in the Footsteps of Florence Nightingale

After retiring as a teacher/administrator in Japan and moving to the Kansas City area in 2005, I had the privilege of teaching a required theology course at Rockhurst University from 2006 to 2015. My classes in sixteen of those seventeen semesters were in the evening, and a majority of my students were in the nursing program.

With few exceptions, those nursing students were serious, hard-working students, and I wonder now how they are faring as practicing nurses during the current pandemic. I am quite confident that many of my former students are a part of the dedicated core of nurses ministering to COVID-19 patients across the country.

I hope they all are all right, but some might not be. According to a recent report by the National Nursing Associations (cited in this article from the International Council of Nurses), at least 90,000 healthcare workers have been infected with COVID-19, and more than 260 nurses have died.

The nursing students I taught (and all dedicated nurses) are following in the footsteps of Florence Nightingale. I write this to honor them (and all nurses) this week, which is National Nurses Week. This special week begins each year on May 6 and ends today (May 12), Florence Nightingale’s birthday.

Thank God for Florence Nightingale, and thank God for nurses!

A version of this article first appeared on Seat’s blog, The View from This Seat. It is used with permission.