Most of us will only have one funeral. The Confederate Lt. General, slave trader, and Grand Wizard of the KKK Nathan Bedford Forrest and his wife, Mary, just had their third.

Originally laid to rest in a Memphis, Tennessee, cemetery following their deaths in the late 1800s, officials moved the couple’s remains in 1904 to a park named in his honor. Following the 2015 shooting at Mother Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina, leaders in the Bluff City voted to remove the Forrest monument. State officials initially barred the actions, so the city sold the park to a non-profit entity that was exempt from the prohibition.

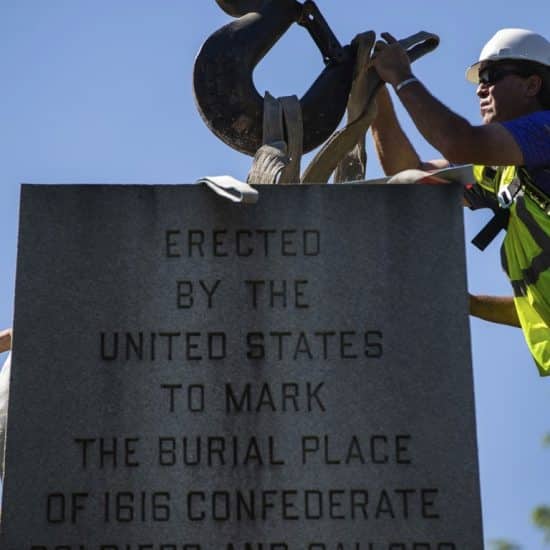

A statue of Nathan quickly came down. Then, in June of this year, the process began to remove the pedestal of the monument and relocate the remains of the couple. The Sons of Confederate Veterans buried the couple again on Sept. 18, this time at the National Confederate Museum in Columbia, Tennessee.

With cannons firing, women dressed in 19th century black dresses and head coverings, and men sporting Confederate uniforms, the latest ceremony sought to honor the man who enslaved people, massacred Black soldiers who had already surrendered, and led a group that sought to maintain White Supremacy through violence. One SCV leader called the internment “a remarkable event” for “one of our heroes.” Even the rain on that day, he added, “was like God was crying, but then the rains, the tears, stopped and gave him the welcome home like it should be.”

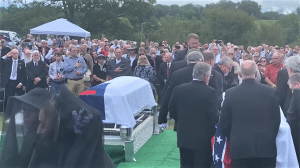

More than rhetoric connected God to the Forrests during the ceremony. Their coffins were draped with flags: his with a Confederate flag and hers with a Christian flag.

Screengrab of pallbearers bringing in Nathan Forrest’s coffin draped with a Confederate flag to place it next to Mary Forrest’s coffin draped with a Christian flag.

The funeral for two “saints” of the lost cause wasn’t the only time this year we’ve seen that unholy conflation of the Confederacy with the Christian Kingdom. We also witnessed the two banners flying together as insurrectionists violently stormed the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6.

The Christian flag’s co-optation at these events raises a banner of questions about its contemporary meaning to the Church. These questions became even more poignant when the U.S. Supreme Court last week agreed to hear a case about flying the Christian flag at a city hall. In this edition of A Public Witness, we unfurl the history of the Christian flag and raise up its usage by White Supremacists today.

For Whose Kingdom It Stands

The design of the Christian flag occurred in 1897, which means the Forrests never even saw the banner that adorned Mary’s coffin last month. As the story goes, when a guest speaker failed to show up for Sunday School at Brighton Chapel in Brooklyn, New York, a local leader gave an impromptu speech. Noticing an American flag draped over the corner of the pulpit, Charles Overton used the flag as “his text” (which seems like an even worse idea than using Leviticus for a sermon text). Overton then imagined aloud to his audience what a Christian flag might look like.

The final product is quite similar to the Stars and Stripes that Overton chose as his “inspiration.” Simply remove the red stripes and white stars, and then add a red cross inside the blue box. A week after Overton’s “message,” he draped a version of his Christian flag on the pulpit along with the American flag. That display served as the prototype for what is now generally called the Christian flag.

A few years later, the flag received a boost from famed songwriter Fanny Crosby, whose canon of more than 8,000 hymns and gospel songs include classics like “Blessed Assurance,” “Pass Me Not,” “Rescue the Perishing, and “To God Be the Glory.” In 1903, she penned “The Christian Flag, Behold It.”

Now throw it to the breeze,

And may it wave triumphant

O’er land and distant seas,

Till all the wide creation

Upon its folds shall gaze,

And all the world united,

Our loving Savior praise.

While the song didn’t take off, a pledge did. In 1908, Rev. Lynn Harold Hough was inspired during a meeting at which a speaker talked about Overton’s flag. Hough unveiled the pledge for use at a Christmas Eve service in 1908 at his church, Third Methodist Episcopal Church in Long Island City, New York. As with the design of the flag, this American minister borrowed from the U.S. counterpart for inspiration.

“I pledge allegiance to my flag and the Savior for whose kingdom it stands; one brotherhood uniting all mankind in service and love,” Hough offered as the pledge.

After the U.S. pledge changed in 1923 from “allegiance to my flag” to “allegiance to the flag of the United States of America,” the Christian flag pledge similarly changed from “my flag” to “the flag.” Additionally, some today say “all Christians” or “all true Christians” instead of “all mankind.”

There is also a version more popular in some conservative churches that declares, “I pledge allegiance to the Christian flag, and to the Savior for whose kingdom it stands; one Savior, crucified, risen, and coming again with life and liberty to all who believe.” Regardless of the version, the use of the Christian flag and a pledge remain common at Vacation Bible Schools and other church moments for children.

As the creation of a song and pledge suggests, the use of the flag quickly took off. This popularity, however, also sparked questions of protocol — especially when rumors of war began to swirl.

Pledging Allegiance

Methodist minister Ralph Diffendorfer, who helped Overton popularize the Christian flag, insisted in 1917 that the banner should be a symbol of unity and peace.

“The Christian flag bears no symbol of warfare or conquest,” he explained. “It stands for no creed nor denomination but for Christianity. It is a banner of the Prince of Peace, and the Christian patriot who salutes it pledges allegiance to the Kingdom of God.”

Crosby similarly sung an appeal for people to “unfurl it” to “bear the message, goodwill and peace to men.”

In light of this background and faced with the looming threat of war, uncomfortable questions began to arise about the allegiance of Christians who waved it.

Rev. James Russell Pollock, a young Methodist minister serving his first church in 1938, placed a new Christian flag in the place of prominence in the sanctuary off to the pulpit’s right and moved the American flag to the left. That symbolically showed allegiance to the Christian Kingdom coming before obligations to one’s earthly country. It also violated the unofficial U.S. flag code created in 1923 that insisted on the U.S. flag receiving top billing (Congress later codified that preference for the U.S. flag in 1942).

During the week after Pollock’s redecorating, someone switched the placement of the U.S. and Christian flags — an action he attributed to the people being “flag-sensitive and overreactive” as the “nation was gearing for war” with alarming news from Europe.

So, Pollock, who would soon serve as a chaplain in World War II, created his own code to justify his placement. In his code, the Christian flag precedes all other flags (but follows the cross if it is part of a processional), and the Christian flag dips to no other flags (but may dip to a cross at the altar). Additionally, the Christian flag should fly at the top position on a pole and maintain the position of honor when displayed together (such as to the preacher’s right when on stage, or from the congregation’s perspective that would mean off to the left of the pulpit).

This was no minor issue. Flag etiquette remains an important topic of consideration for issues of authority and allegiance. The word “allegiance” conjures an era that Americans generally don’t understand. The word came to English from the Anglo-French term legaunce, which described the loyalty a vassal or servant owed to their lord (or liege). When we pledge allegiance, we are submitting to a master or lord. We’re saying that this lord — be it a person, a god, a nation, an ideology, or whatever — gets to decide what we believe and how we live.

Thus, we can only offer our ultimate allegiance to one lord/nation. Or as Jesus put it, we cannot serve two masters. Flag placement, as Pollock understood, suggests to whom we truly pledge allegiance.

Many churches today arrange the U.S. and Christian flags according to the U.S. flag code (like in this photo), rather than as Pollock urged. (Brian Kaylor/Word&Way)

The month after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor and brought the U.S. officially into World War II, the Christian flag came up for conversation at a Jan. 23, 1942, meeting of the Federal Council of Churches (an ecumenical organization today known as the National Council of Churches). As the story often goes, the FCC adopted the flag and therefore gave it an authoritative status. But the actual minutes from the meeting instead offer some warnings.

The FCC noted a few examples of “Christian” flags, and acknowledged Overton’s design as “the form most generally regarded as the Christian flag.” But the resolution didn’t actually adopt it. And the FCC insisted it wasn’t “attempting to prescribe regulations” but just offering “advice to churches” after having “received overtures and inquiries concerning the appropriate use and position of flags within the sanctuary.” At a moment when many were thinking about waving flags at the start of a war, the FCC resolution offered caution about ultimate allegiance.

“The Cross itself is generally accepted as a good and sufficient symbol for the house of God in the Christian tradition, without the use of a church flag,” the FCC resolution offered. “If a flag or banner representing the loyalty of the church to its Head is used along with the flag of the nation in the sanctuary, the symbol of loyalty to God should have the place of highest honor.”

So, the FCC actually recommended the use of just a cross. And the FCC followed Pollock’s ordering if a Christian flag appears along with the U.S. flag by outlining in the resolution where the flags should stand in relation to each other. Despite these efforts, Overton’s Christian flag shows up in church sanctuaries throughout the country, usually positioned to the left of the preacher and therefore in a subservient position to the U.S. flag on the right.

A danger of creating symbols is losing control over their use. They can send different and even conflicting messages than what their creators originally intended.

Get cutting-edge analysis and commentary like this in your inbox every week by subscribing today!

Great Replacement

As insurrectionists violently stormed the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, the crowd carried a number of symbols to explain their loyalties and ideologies. Flying alongside numerous Trump flags were Confederate and Christian flags. Overton’s symbol for everyone — the flag Diffendorfer called a banner of peace — was employed as a symbol for a partisan group bent on undermining American democracy.

Insurrectionists outside the Capitol building on Jan. 6, 2021. (Lev Radin/Sipa USA via AP)

Many commentators correctly noted the presence of Christian flags as a sign of the White Christian Nationalism that helped fuel the mob. We suggest the problem is even worse than that. The insurrection also shows us that White Supremacists are clearly adopting the Christian flag as their own, changing its meaning and denying its fundamental message that “Jesus is Lord.” It’s presence alongside the Confederate flag at partisan rallies and political funerals is not an accident. To those presenting these colors, the two symbols are synonymous in meaning and interchangeable in use.

That’s why we saw the two flags paired together at the (re)reinterment of the Forrests despite the anachronism of burying the deceased in a flag that didn’t exist during their lifetimes. For those who still believe in the “lost cause,” their horrid purpose is righteous and their wretched beliefs in line with the will of God.

Thus, during a 2015 pro-Confederate flag rally pushing back against demands that the Confederacy’s banner be taken down in various public spaces, some of those present also waved Christian flags as a symbol they found compatible with the stars and bars. And after NASCAR banned Confederate flags in 2020, a racetrack owner in North Carolina announced a “heritage night” to “protect the sport we love.” He advertised it as a time to come “purchase your Confederate flags and caps here, along with your Christian flag, American flag, Donald Trump flag and caps.”

This perspective of viewing the Christian flag as aligned with the Confederate cause is also seen in those instances when raising the Christian flag is offered as an easy replacement for taking down a Confederate banner. Consider a few examples:

- In 2015, a local member of the Sons of Confederate Veterans in Harleyville, South Carolina, told the Post and Courier the week after the Mother Emanuel shooting that he rotates flying a Confederate flag, Christian flag, yellow Gadsden flag, and the state flag.

- In 2015, a group that installs Confederate flags in Virginia replaced one in Danville at Christmas time with a Christian flag because they also put a nativity scene at the base of the pole.

- In 2018, the Richmond Free Press published a photo of a Confederate flag flying in a city-owned cemetery with the headline “Why is this flying?” The flag in question was erected and owned by the United Daughters of the Confederacy. The flag was replaced a few days later, apparently by the UDC, with a Christian flag.

- In 2020, a local Sons of Confederate Veterans group in Burke County, North Carolina, briefly replaced a large and controversial Confederate flag with a U.S. and Christian flag on a flag pole that flies prominently above Interstate 40. The replacements flew during the two months just before the presidential election, and then switched back to a Confederate flag.

Such back-and-forth swapping between the flags occurs because of claims by defenders of the Confederate battle flag that it is a “Christian” symbol for what they believe was a “Christian” nation. With White Supremacists needing more palatable symbols amid a backlash to Confederate imagery, we will likely see an increased effort to co-opt Christian symbols like Overton’s flag to convey these ugly messages.

In these moments, the flags are flown to make a statement. They are acts of defiance, plain and simple. We should not mistake the replacement of one flag for another as gestures of contrition that indicate repentance. The underlying beliefs of the ones hoisting the banner remain unchanged.

North Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, in April 2017. (Alex Holder)

Help sustain the ministry of Word&Way by subscribing to A Public Witness!

Symbols Matter

As we watch White Supremacists claiming the Christian flag as their own symbol to complement or even stand in for a Confederate emblem, we remember a warning of history: Symbols don’t necessarily keep the meaning intended by their creators. For instance, the swastika is an ancient symbol dating back to at least the time of King David, and took on religious meaning for Buddhists, Hindus, and other eastern Asian religions. Then the Nazi regime co-opted the symbol, transforming it forever into a deplorable emblem of White Supremacy, anti-Semitism, and vile hatred.

Moving in the other direction, early Christians adopted a symbol of torture and death — the cross — because Jesus’s death and resurrection gave it new meanings of forgiveness and love, victory and liberation. It is the holiness of that symbol and its central meaning to our faith as followers of the crucified servant that should inspire us to protect its sacred meaning. This emerging trend that hijacks powerful Christian imagery and imbues it with connotations of hatred should be abhorrent to all who place their ultimate loyalty in Christ.

We’re not particularly fans of Overton’s overly American design for the Christian flag. We’re troubled when church sanctuaries display the symbol in ways suggesting, however inadvertently, that the Kingdom of God is subservient to a human nation. From our perspective, the Federal Council of Churches got it right back in 1942 when they recommended focusing on the cross over the flag.

Still, what worries us even more is when White Supremacists seem bent on turning the Christian flag, the cross stitched upon it, or any Christian symbols into banners for their ideology. We must speak out when we see Christian flags employed alongside Confederate flags like at the Jan. 6 insurrection, or at a funeral service commemorating Confederate leaders, or when people act like the Christian flag is a perfect substitute for a Confederate banner on a flag pole.

If Christians don’t criticize these moments and contest the efforts to hijack sacred imagery, we will continue to see our treasured symbols used with hostile meanings. As the Apostle Paul wrote, he was called to keep preaching the Gospel “lest the cross of Christ be emptied of its power.” In this moment, that call to faithful vigilance and persistence belongs to us all. The stakes are too high to wave the white flag.

As a public witness,

Brian Kaylor & Beau Underwood