(RNS) — If someone had asked Matthew Dowd on Jan. 1 whether he’d be running for public office in Texas, he would have laughed. But then, said the veteran political strategist and pundit, came the Jan. 6 insurrection.

“I thought it was the worst threat to our democracy since the opening shot of the Civil War,” Dowd said.

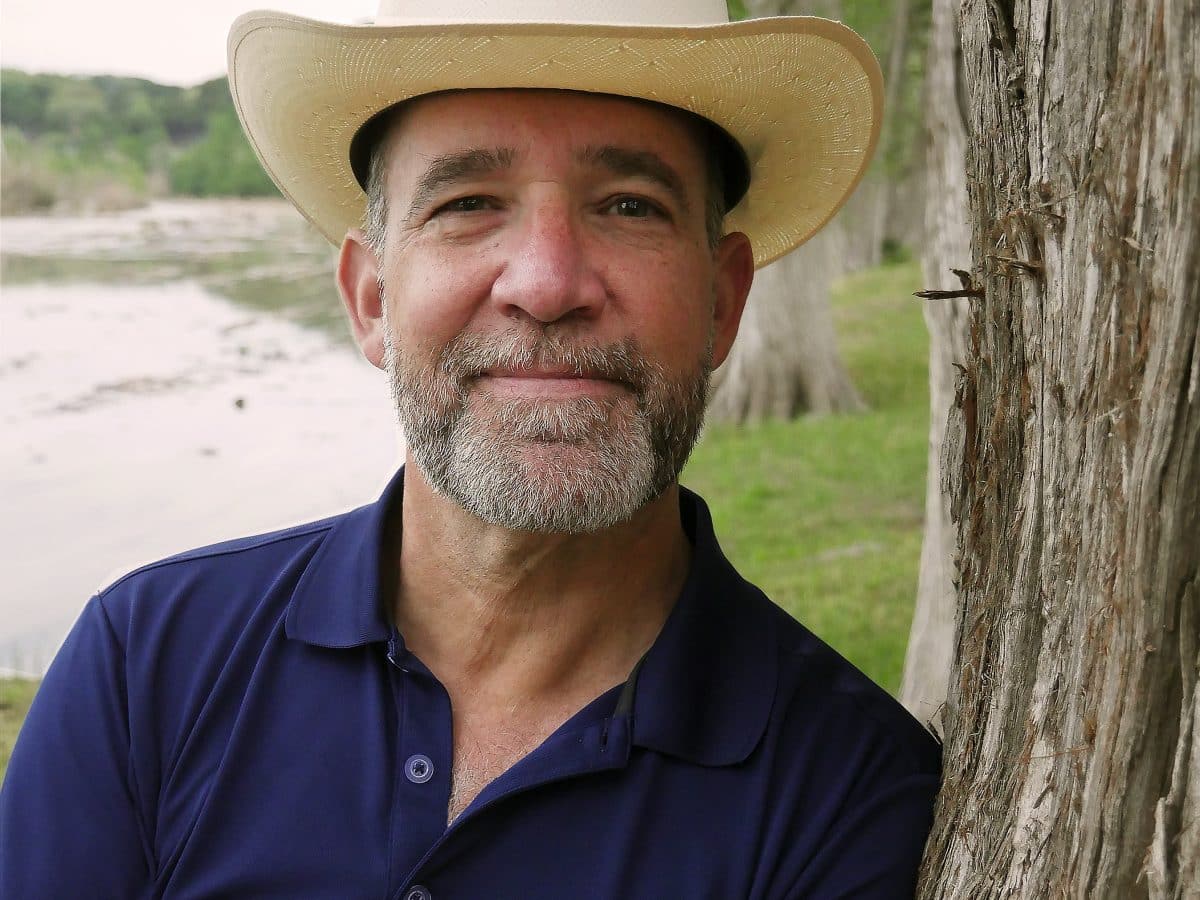

Matthew Dowd poses by the Blanco River in Wimberley, Texas. (Religion News Service)

On Sept. 29, the former campaign aide for George W. Bush and Arnold Schwarzenegger and onetime ABC pundit announced on Twitter that he was running for lieutenant governor as a Democrat. If he gets past a primary this spring, he will take on incumbent Republican Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick.

Dowd, who was Roman Catholic but now attends a nondenominational church, said he did a lot of meditating and praying before choosing to subject himself to the rigors of waging his first campaign as a candidate.

“It was a decision based in huge part on my own faith,” he said.

That faith, Dowd said, has led him to root his campaign in a belief that truth can overcome lies, love overcome hate, and good can overcome evil in a turbulent moment in history. “If we step up, it can happen. I hope that I and others have the courage and strength to do what is necessary in this time.”

Dowd’s embrace of a challenge bigger than oneself is as much a political bet in his state as it is a spiritual odyssey. Rated as one of the most partisan states in the nation, Texas has a record of electing politicians who aren’t prone to compromise. Will Dowd’s Christian credentials and openness to working across faith lines appeal to voters put off by regular and predictable hostilities among lawmakers?

The last Democrat to win statewide was Lt. Gov. Bob Bullock. That was in 1994.

(While two journalists don’t a trend make, New York Times fixture Nicholas Kristof, known for his faith-inquisitive columns, announced recently that he’s also leaving his post, to run for governor of Oregon. )

“Common Sense. Common Decency. For the Common Good” is Dowd’s campaign slogan. He’s interested, he said, in nurturing hope and finding a way for everyone to participate in creating a brighter future. His reading of the Gospels tells him that the means matter more than focusing like a laser on the end result.

“Let go of the kingdom of God, of the afterlife, let go of all that,” he told Religion News Service. “Do what is necessary in the moment, in a loving and kind way, and the kingdom of God will take care of itself.”

“I’m just going to be who I am, speak from my heart and soul,” said Dowd. “However, the universe responds to that, I trust in God. I’ve been blessed in my life. I just felt a call to do more at the moment. That comes in large part from my faith.”

Dowd’s emphasis on faith, broadly construed, will come as no shock to the candidate’s national audience. He is already known for tweeting out poetry, Scripture and other inspirational content to his more than 250,000 Twitter followers. In the Trump era, he said, he “incubated, in my social media, a group of folks that have similar thoughts about how we embrace kindness, but also strength, how to push back in a way that isn’t cruel or mean.”

These days Dowd’s feed has filled up with comments on local and national issues, such as paid family leave and gun violence, as well as direct challenges to Patrick.

But Dowd’s latest book, Revelations on the River: Healing a Nation, Healing Ourselves — his third — doesn’t shy from difficult questions of faith. Why, he asks, would one accept only revelation or epiphany that came a few thousand years ago in the form of an inspired Bible (Old and New Testaments) to one tribe, at one time, and in one way? Wouldn’t God (or whatever name you give the divine) want to reveal truths at many times in divergent ways and faith traditions? Isn’t the act of creation revelation in itself, and the beauty of our world a constant form of epiphany?

Dowd’s willingness to speak plainly about his beliefs is a growing trend among even the bluest Democrats, said Lerone Martin, a professor of religion and politics and director of the American Culture Center at Washington University.

“We are increasingly finding that (Democrats) talking about their faith, and how their faith leads to very different policy conclusions,” said Martin, citing Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi, a Catholic; New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker, a member of a National Baptist Church; and Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren, who identifies as a Methodist.

While areas of America, like the coasts, are indeed growing more secular, Martin said, religious beliefs still matter, particularly in the South, the Southwest, and most of the Midwest.

“People want to know what church you go to. They want to know how your faith shapes your worldview,” Martin added.

Dowd said he owes his faith to the books and influence of the late Rev. Thomas Keating, a Trappist monk, who helped him hone his early morning practice of centering prayer, and for much of Dowd’s life he was a “regular churchgoing Catholic.” But since he began his walk away from Republicanism, he has investigated the thought of Buddhism and the nonviolent spirituality of Mahatma Gandhi and has spent time in India walking in those leaders’ footsteps.

His spiritual politics may be best expressed by his choice of church. When he moved to Wimberley, Texas, southwest of Austin, the cradle Catholic opted to attend the interdenominational Wimberley Chapel in the Hills.

The church’s mission statement could be a commercial for Dowd’s campaign. It was founded in 1949 by laypeople of many denominations, said its current pastor, Jim Denham: “The primary reason for starting this church was fellowship. Let’s be here in the community, enjoy each other, and we do the essentials of faith.”

When someone wants to join, Denham said, he tells them two things: Because of the blending of denominations found in the pews, it’s important to maintain harmony. He added, “We can’t be getting into an argument about one way to do certain things.”

Secondly: “Leave politics in the parking lot,” said Denham, who said that he works hard to keep his political opinions private.

Though Denham said that he wasn’t sure how, or if, having a high-profile candidate in the church would affect the congregation, he described Dowd as an “honest and decent guy. We need more of those people. In reading his book A New Way, I grew to have a deeper understanding of him politically and appreciated his spiritual journey. It showed so much integrity.”

Some political analysts say Texas is slowly trending blue, giving Democrats a bigger chance at future success, in spite of Republican control of the redistricting process.

“Texas is an interesting state, where politics and ideologies are shifting,” said Dartmouth College government professor Mia Costa.

Voters do care about issues and policy, she said, but “they also want, increasingly, someone that they can feel connected to in a personal sense. Maybe that’s why also experience, credentials, being an established career politician is becoming less and less important.”

But Texas is not blue yet. Can a Democrat find the right mix of interfaith values voters to get over the top?