(RNS) — In March 2012, Katy Attanasi, then an assistant professor of religion at Regent University in Virginia, was at home feeding her newborn son when she heard a knock at the door. On her stoop, she found a snow-dusted FedEx envelope from the university. Inside was a letter informing her that her faculty contract would not be renewed.

Attanasi, now a Methodist pastor in Kentucky, was one of eight faculty to receive a Fed-Exed termination letter that semester. Hers was signed by Gerson Moreno-Riaño, dean of Regent’s School of Undergraduate Studies. No warning had been given and no explanation followed.

“We didn’t have anything else lined up, and my husband had just had surgery,” said Attanasi. “We were looking at a future with a baby with a preexisting condition and no health insurance. It was a very frightening time.”

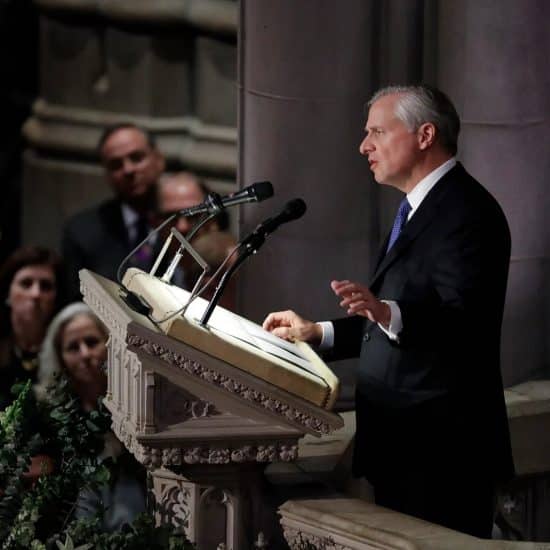

Gerson Moreno-Riaño. (Religion News Service)

Scouring the faculty handbook, Attanasi found that as a tenure-track faculty member, she was guaranteed a terminal year contract, which she argued for and completed in 2013. Since then, former Regent employees claim, at least 39 others — administrators, faculty, and staff — were also let go as Moreno-Riaño rose to executive vice president for academic affairs.

Those who were terminated were often seen as “going against the conservative evangelical grain of the university,” according to Walter Staggs, a former writing center director at Regent.

“It was traumatic for everybody,” said another former Regent staffer.

Regent spokesperson Chris Roslan said that “Regent has not had any ‘faculty purges,’” adding that the university had ended “underperforming programs” and as a result a “small number of faculty” were “not renewed at the end of their contracts.”

Last May, Moreno-Riaño was appointed as the 12th president of Cornerstone University, a small, Christian liberal arts school in Grand Rapids, Michigan. The day before his formal installation in October, Cornerstone’s faculty voted no confidence in his ability to lead as president, citing a culture of “fear and suspicion” and the last-minute departures of at least eight faculty and staff.

Attanasi and some of her former colleagues at Regent called the pattern at Cornerstone eerily familiar.

The events at Cornerstone and Regent are bigger than any one administrator. Politics have exerted a strong influence on Christian schools in recent years, said Scot McKnight, a Cornerstone alumni and now professor of New Testament at Northern Seminary in Lisle, Illinois.

“There is a polarization in Christian education today that lines up too neatly with partisan politics,” said McKnight. “Many of these schools are now making decisions about which partisan group they are going to align themselves with, which turns an institution away from critical thinking and toward partisan politics.”

Attanasi compared the targeting of certain Regent professors to dismissals at Liberty University in Lynchburg, Virginia, after the school’s then-president, Jerry Falwell Jr., championed Donald Trump’s White House run in 2016 and invited him to campus. (Trump also held a campaign rally at Regent and was later interviewed there by its founder, Christian media executive and star Pat Robertson.) Liberty also saw a dramatic drop in Black students under Falwell.

“I unfortunately see the reality of this institution becoming like the next Liberty University,” said one Cornerstone employee, “where students of color are slowly but surely eked out. Or they just know they are going to continue to face what Christians do, which is racism.”

Cornerstone has not commented directly on its faculty’s no-confidence vote, but an email sent to faculty on Nov. 19 affirmed the board’s commitment to “Biblical diversity and inclusion” and promised both “mission-centric hiring and retention of diverse faculty and staff.” (All of the terminated Cornerstone employees were said to be involved in promoting diversity, equity and inclusion efforts.)

In a Nov. 22 email to Religion News Service, Carole Bos, chair of Cornerstone’s board of trustees, wrote, “Our board of trustees has been very appreciative of those who have raised concerns and offered ideas on how we may continue to best fulfill our mission. Moving forward with President Gerson Moreno-Riano, the board remains committed to our Cornerstone Identity, Mission and Vision.”

But the atmosphere at the school remains unsettled. Deja Terhune, a senior secondary English education major at Cornerstone, said she hadn’t received any information about the faculty and staff who have departed. “There is no transparency at all. No one is saying anything, everything is very secretive at the moment,” she said.

Some students of color have spoken out about what they view as the president’s distaste for diversity programs.

“The gaslighting, spiritual abuse, racial microaggressions, removal of faculty and lack of safe spaces for people of color has been detrimental to my mental, emotional, and spiritual health and I am now seeing a therapist I hardly afford and have moved off campus to have space to breathe, rest, and recover from CU,” wrote Lamont Aldridge, a junior and intern in the school’s diversity department, in a letter shared with faculty on Oct. 21. “I do not trust the new administration or changes made to lead to the flourishing of our university, especially for marginalized students.”

At Regent, Moreno-Riaño was successful in bolstering enrollment, which nearly doubled during his tenure, thanks in part to an increase in online degree offerings. But several former employees allege the restructuring was used as an excuse to remove employees who challenged the status quo, especially on matters of social justice.

“The cuts that I saw were where they used the budget to justify getting rid of people whose scholarship was not seen as being extreme-right enough, fundamentalist enough,” said Kimberly Alexander, a former associate professor of the history of Christianity at Regent’s School of Divinity who resigned last year.

Alexander said administrators questioned her about her scholarship, which she described as being “conservative” but involving some “feminist language.”

Rev. Antoinette G. Alvarado, former adjunct professor at the School of Divinity, said that in 2016 she received an email from James Flynn, an associate dean, instructing her to stop assigning students a video of Rev. Jeremiah Wright — a dynamic Chicago pastor whose critiques of the United States made headlines in 2008 when it was reported that then-candidate Barack Obama had attended his church.

Flynn “stated in the email that (the) new vice president of academic affairs, had reviewed my curriculum and the sermon preached by Dr. Jeremiah Wright that I had assigned for my class to review was not acceptable for Regent School of Divinity,” wrote Alvarado in an email to RNS. The new vice president was Moreno-Riaño.

“I didn’t understand, because the part of the course was on Black preaching, and (Wright) is one of our hallmark preachers. And after I received that email, they never offered me another contract,” said Alvarado.

“Over and over, people were just disappearing,” said Staggs. “You realize, this is more like the Christian mafia. You can’t talk against the family or you’re gone.”

Staggs and Alexander said Moreno-Riaño acted in coordination with Corné Bekker, dean of the School of Divinity at Regent. As a member of the curriculum committee, “we were essentially just rubber-stamping curriculum,” Alexander said. “It was very much stated that this was a correction of the errors of the past, where the school had become too liberal or too diverse.”

The academic changes did not go unnoticed by students. “I felt like it was shifting away from a traditional, academic model with traditional, academic values, where inquiry, open exchange of ideas and scholarship are celebrated,” said Vincent Staggs, a former divinity student at Regent and now a professor at the University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Medicine. (He is not related to Walter Staggs.) “I felt like it was shifting away from that to a more ideologically narrow, controlled model.”

Jermaine Marshall, who was in a Ph.D. program at Regent’s School of Divinity from 2012-2019, agreed. “When I entered the School of Divinity, it was a world-class institution,” said Marshall, now pastor of Williams Institutional CME Church in Harlem. “It was a phenomenal place to study, a place of academic rigor, critical inquiry and critical thinking. Unfortunately, that does not exist there any longer.”

Students alarmed by the departure of School of Divinity faculty and the changing environment sent letters and petitions to Moreno-Riaño asking him to intervene. He did not. Marshall said he also witnessed a decrease in the ethnic and racial diversity of School of Divinity faculty.

“When I entered the School of Divinity, we had good diversity on the faculty, but over time, and particularly when Gerson was VP of academic affairs … that diversity just dissipated,” said Marshall, referring to Moreno-Riaño by his first name. “In many cases, people of color, they were either let go, or because of instances of either covert or overt instances of racial discrimination, they left.”

In a statement to RNS, Roslan said, “Regent University is deeply dedicated to advancing principles of academic freedom as is defined in its Faculty and Academic Policy Handbook. This policy allows for the fostering and free exchange of knowledge and a wide variety of ideas consistent with traditional Christian principles.” Roslan said 40% of Regent’s administrators campuswide are women and people of color, and he rejects any claim that the school discriminates against any race or gender.

“What’s going on at Cornerstone, it’s a playbook,” said Alexander. “It’s the same thing, except he’s gone in with this kind of license to do what he’s done.”