(RNS) — Let me take you down to Strawberry Fields— no, not the memorial in New York’s Central Park to the former Beatle John Lennon, who was slain in Manhattan in 1980, but to the place that inspired his song, where the Salvation Army is conducting an experiment in mixing tourism with faith and social action.

The original Strawberry Field was a children’s home in Liverpool, just around the corner from John Lennon’s childhood home. It inspired the Beatles’ 1966 track “Strawberry Fields Forever,” penned by Lennon (who added an “s” to its name), as well as what may be one of the most innovative projects undertaken by the Salvation Army, the Christian anti-poverty movement founded in mid-1800s London.

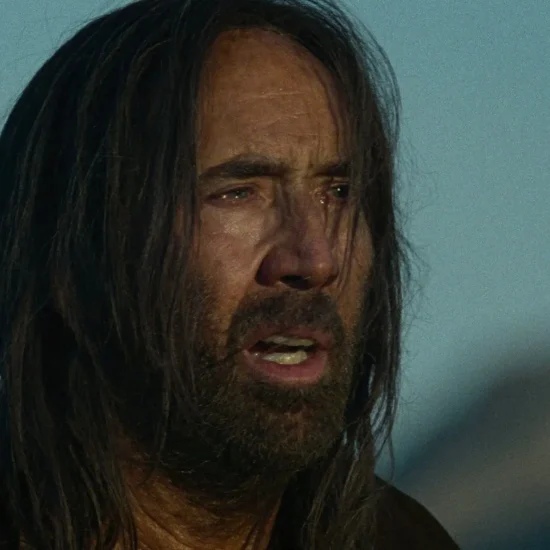

Mission director Kathy Versfeld at the famous red gates of Strawberry Field in Liverpool, England. (Photo by Catherine Pepinster)

Strawberry Field is known for its red gates festooned with strawberry motifs, which are often thronged with tourists taking selfies and some adding to the graffiti on the gates’ stone pillars. But the army has now deployed the site’s connection to the Beatles to draw more visitors to fund its mission and encourage people who would never consider stepping inside a church to find out about Christianity.

The children’s home, closed in 2005, has been demolished. In its place is a new structure that contains a prayer space, a café, and an exhibition about Lennon and the Beatles that includes one of Lennon’s pianos. The building also houses a training project to help young people with special needs get into work.

Stymied by COVID-19 pandemic closures when it first opened in September 2019, it is at last coming into its own. Last year Strawberry Field welcomed 120,000 paying visitors; this year the Army expects even more. International Beatles Week, which started Thursday (Aug. 22), will put it on the tourist trail that includes the nearby childhood homes of Paul McCartney and Lennon, local Beatles museums and other landmarks.

But none of the rest combine religion with Beatles tourism.

The piano on which John Lennon composed “Imagine,” loaned to Strawberry Field by the George Michael estate, on display at the Salvation Army museum in Liverpool, England. (Photo by Catherine Pepinster)

The Strawberry Field project is the result of years of discussion and prayer by the Salvation Army after it closed the children’s home. The worldwide movement, founded by William and Catherine Booth to work in urban slums, became known as the Salvation Army in 1878. It adopted a quasi-military structure, with officers rather than clergy leading it and members wearing uniform. Its membership across the world of 1.5 million still focuses on social action, and its officers, like Strawberry Field’s mission director, Kathy Versfeld, still wear the uniform.

Lennon is not a natural icon for a Christian organization. In 1966, he told an interviewer that his band was “bigger than Jesus,” and opined that “Christianity will go. It will vanish and shrink.” In the uproar that followed, more than 30 U.S. radio stations banned Beatles’ tracks, and young people were urged to burn their Beatles records and memorabilia.

In August 1966, as the Beatles launched a U.S. tour, Lennon said at a press conference, “I’m not anti-God, anti-Christ, or anti-religion. I was not knocking it. I was not saying we are greater or better.” Rather than comparing himself to Christ, he said, he was trying to explain the decline of Christianity in the U.K. (which has indeed seen more prosperous days).

Considering this history, honoring Lennon took more than a leap of faith, according to Versfeld. “The Salvation Army through its research discovered a surprising fact, and that was that every year 60,000 John Lennon fans and Beatles fans were bringing themselves uninvited to the red gates, and many came not knowing what Strawberry Field was,” she said.

“The Salvation Army realized there was the potential not just for a commercial operation here,” she added, “but an opportunity for engagement with those individuals who would not quickly come through the doors of a Salvation Army church or center.”

The refrain of Lennon’s song — “Let me take you down, to Strawberry Fields” — is reflected in the Salvation Army’s invitation to explore its site, including the gardens where Lennon used to play. He later remembered visiting the home’s annual summer fete with his Aunt Mimi.

The Beatles interactive display at Strawberry Field in Liverpool, England. (Photo by Catherine Pepinster)

Paul McCartney, who wrote his song “Penny Lane” about his own childhood memories of Liverpool, in response to Lennon’s memories of Strawberry Field, has said that the Salvation Army home and gardens were a utopia for the young Lennon.

“The bit he went into was a secret garden … and he thought of it like that, it was a little hideaway for him … living his dreams a little, a getaway. It was an escape,” McCartney says in Craig Brown’s biography of The Beatles, “One, Two, Three, Four.”

The Salvation Army said that it wants visitors to Strawberry Field to be able to “find out more about what it means to explore spirituality and faith” and that the Army strives to be “an inclusive community with God at the centre … but you do not have to belong to a Christian church — or any religious tradition at all to take part in what’s on offer here.”

Versfeld and her team want to challenge people who visit the center: “Strawberry Fields Forever — but what does last forever?,” she said. “What does abundance look like and what does it mean for us to open the gates and to do good?”

Lennon’s song “Imagine” is highlighted at Strawberry Field as an anthem for peace, its words carved in stone in the garden. The upright Steinway piano, on which he composed the song, is on loan to the site from the estate of the late British singer-songwriter George Michael, who bought it at auction in 2000.

The bandstand, in the shape of a drum, at Strawberry Field in Liverpool, England. (Photo by Catherine Pepinster)

According to Allister Versfeld, Kathy’s husband and development director of Strawberry Field, it was the Salvation Army’s mission that convinced Michael’s representatives to lend the piano. “They spent the day here; it was the work done here that convinced them it should come here,” he said.

Visitors today are invited to assist in Strawberry Field’s employment and training programs, Steps to Work, which are supported in part by the £11.20 admission fee — about $15 — for the Beatles interactive display, together with spending in the café and the gift shop. A ukulele band is among those who volunteer their time; on a recent day their version of the Beatles’ “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da” filled the café. In the garden is space for people to spend their time in contemplation, while at a far end is a giant bandstand shaped like a Salvation Army drum.

“This drum is on its side because in our early days people would see the band marching down the high street, and the drum would be used as a place of prayer,” explained Versfeld.

The doors are open seven days a week for tourists and local people alike. When the Versfelds arrived, the famous strawberry gates had been shut for years, but now, says Kathy, “The gates are open for good.”