AMMAN, Jordan (RNS) — Preparing breakfast on a recent morning, Amany Khraisat listed imported products she stopped purchasing after Oct. 7. Instead of buying American condiments, the mother of two now chooses a local Jordanian brand. Instead of a Western laundry detergent, she’s switched to an Egyptian one. She no longer orders from McDonald’s or KFC, and she shops at C-Town, a Jordanian grocery chain, rather than Carrefour, a French company.

Khraisat is one of millions of Jordanians participating in a grassroots-level boycott that swept the Middle Eastern country after war broke out in Gaza between Israel and Hamas nearly a year ago. A May 2024 poll conducted by the Jordanian research firm NAMA Strategic Intelligence Solutions showed that 83.1% of Jordanians are refusing at some level to buy certain imported products because of the conflict.

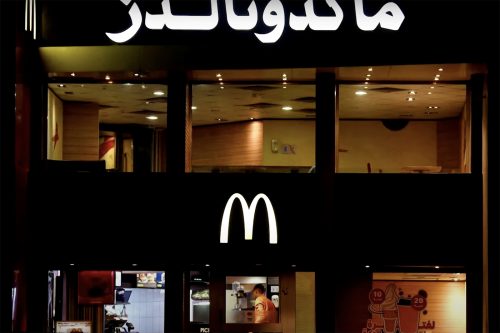

People in a variety of Middle Eastern countries have been boycotting McDonald’s since the Israel-Hamas war. (Video screen grab)

“The boycott has become our religious duty, like giving alms, fasting, and the other pillars of the faith,” said Khraisat, a Muslim.

Initially, some denied that the boycott had religious backing, Khraisat explained, until a saying of the Prophet Muhammad began to circulate on social media: “Strive … with your wealth and yourselves and your tongues,” using the Arabic word for “strive” that is related to the noun “jihad,” encompassing both armed and spiritual struggle against the enemies of Islam.

Though Khraisat does not have Palestinian roots — her father was Jordanian and her mother Syrian — she, like many Muslims, calls the Palestinian cause her own. And like Muslims worldwide, she considers Jerusalem’s Al-Aqsa Mosque — located in an area known to Jews as the Temple Mount, the site of Judaism’s ancient temples — to be the spot where Muhammad ascended to heaven.

About half of Jordan’s 11 million citizens do claim Palestinian ancestry, and some, such as Hanaa Elyyan, still have relatives living in Gaza. In the first days of the war, more than 40 members of her sister-in-law’s family died when their building was bombed. In May, her maternal aunt and cousin died when an Israeli bomb landed near their home.

Elyyan recalls a recent phone call with an aunt who also lives in Gaza. “She told me, ‘We hope our Lord will take us because we are not able to endure this suffering. … We don’t want to live — we’re done. We’re weary. We’re not able to feed our children, we’re not able to endure the injustice, we’ve moved five or six times during this war.’”

Elyyan’s family, Palestinians originally from two farming villages near Gaza, was expelled by Jewish forces in 1948, during Israel’s war for independence. They fled to nearby Gaza City, where they gradually rebuilt their lives, only to be forcibly displaced again in 1967 as a result of the Six-Day War. This time they fled to Jordan on foot.

She sometimes feels helpless as she listens to the news, but said boycotting has given her a tangible way to resist. She’s taken to heart the words of Kuwaiti religious scholar Sheikh Othman Al-Khamees: “The boycott is the least we can do.”

In a speech delivered in October 2023, the Islamic jurist cautioned Muslims to carefully examine companies that purportedly support Israel, warning that rumors on social media have in some cases misidentified such companies. Many Jordanians, however, are simply avoiding any products made in the U.S., which supports Israel with more than $3 billion annually.

Sheikh Othman Al-Khamees in October 2023. (Video screen grab)

Echoing the calls of other Muslim leaders, Al-Khamees called on Muslims to persist in the boycott, describing it as an expression of “zeal” for their brethren in Gaza and for Islam in general. “Do something to let (Palestinians) feel that we are with them,” he said.

Hamzeh Khader, a Palestinian-Jordanian member of the Jordan BDS (Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions) movement, said the number of Jordanians committed to the boycott surpasses that of any other Arab country. He cited a study conducted by a research center at the University of Jordan in early 2024. It concluded that more than 94% of Jordanians are boycotting.

Jordan launched its BDS branch in 2014 in response to an Israeli military operation in Gaza. While the movement has spearheaded other boycotts in the last decade, Khader says the current iteration differs from previous ones because this war has lasted so long. The more Israel pursues its enemies into Muslim-led countries, he said, the more enthusiasm Jordanians exhibit for boycotting, which he considers an effective way to express their anger.

In the boycott’s early days, some store owners taped handwritten signs on beverage coolers, warning customers that the drinks inside were boycotted. Soon, methods grew more sophisticated; large supermarkets labeled Jordanian products to encourage customers to buy local. Now apps such as “I’m Boycotting” and “My Cause” help shoppers determine which brands and stores to avoid. Across Amman, giant ads for local brands splash over billboards.

Not all are convinced of the boycott’s rationale. Raad Haddadin, a Jordanian Christian who owns a minimarket in Amman, personally continues to buy foreign brands and support local franchises of Western companies, believing he’s supporting the Jordanian employees, some of whom are university students paying their way through school.

But at his store, Haddadin quickly realized, he wouldn’t be able to withstand Jordan’s boycott fever. After Oct. 7, customers who entered his shop were searching for local alternatives, and some asked why he still carried brands such as Pepsi and Coca-Cola instead of rising-star alternatives such as Matrix. “I didn’t decide to join the boycott,” he said. “I was forced to join the boycott because of the nature of my business.”

Christians in Jordan compose about 2% of the population, and Haddadin said many are committed to the boycott, driven more by ethical principles than by religion, and by a desire to show empathy and a shared sense of humanity with suffering Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank. “No one would like to have his family or her friend killed in such a way — from any religion,” he said.

Of the seven years he’s owned the minimarket, Haddadin said this year has been the toughest. He doesn’t make as much profit on local brands, which differ from their imported counterparts in quality and flavor. Once the war ends, he thinks, people will return to the products they purchased before it started. In the end, he predicted, those who lose in the boycott won’t be big Western companies but local ones that are mushrooming at an unsustainable pace.

Khraisat continues to boycott, though she acknowledges that not everyone shares her conviction. “We can’t force people (to boycott), because this is something that springs from religion,” Khraisat says. “It comes back to an individual’s faith, if he’s convinced that this thing is right or wrong.”