(RNS) — Elket Rodríguez, the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship’s global migration advocate, has served migrants on the Texas-Mexico border for years. But until earlier this month, he had never been to the Darien Gap, a dangerous jungle route many migrants traverse as they move from Colombia to Panama, most often en route to the United States.

In early November, just days after former U.S. President Donald Trump was elected to a second term, Rodríguez joined a pilgrimage sponsored by Como Nacido Entre Nosotros, or “As Born Among Us,” an ecumenical Protestant Christian network working on migration issues. “It’s a level of vulnerability, even much higher than what I see at the border,” Rodríguez said of his experience.

Volunteers with Como Nacido Entre Nosotros, in blue shirts, distribute donations to migrants at the Lajas Blancas migrant reception center, Nov. 8, 2024, in southern Panama. (Photo courtesy of Como Nacido Entre Nosotros)

The trip brought 25 Latino Protestant leaders and pastors to Panama to help them understand the experiences of migrants who arrive in their communities and to explore opportunities to collaborate with Panamanian churches and other partners to support migrants. Participants came from 10 Latin American countries and several states across the U.S., and included representatives of Mission Talk, Latino Christian National Network, Mygration Christian Conference, and Avance Latino.

The Rev. Carlos Malavé, a southern Virginia pastor of two churches and president of Latino Christian National Network, said he was motivated to go on the trip because “it’s not the same to listen or hear about stories as a religious leader in the U.S. than experiencing face-to-face the pain of people,” saying he’d heard “horrific stories” and understood “the reasons why they risk their lives” when he was in Panama.

Many of these pastors count immigrants from Latin America among their congregants. Even for their churchgoers who have not migrated, a story of a loved one’s migration is always close at hand.

“The person who arrives here is already bathed, clean, and ready. They’re only thinking about work, about the next thing, about beginning to grow and beginning to produce,” said the Rev. Rubén Ortiz, Latino field ministries coordinator for the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship, who took a leading role in the two Darien Gap pilgrimages sponsored by the Como Nacido Entre Nosotros network. Ortiz, a Cuban immigrant who now lives in Deltona, Florida, where he formerly pastored a church, now coordinates the work local churches in his denomination do with migrants, including food distribution and connecting them with services.

“We want people to understand where this person comes from and to understand the traumas and possible circumstances that they will find in their pastoral life with them,” Ortiz explained. “It would be terrible, for example, to deport them,” he said, “because those people have already lived trauma.”

Beginning their work in Panama on Nov. 8 — two days after Trump, who campaigned on a platform that included mass deportations, had been declared the winner — was an experience of “grief,” Ortiz said. “It wasn’t easy at all because many of us had no words of hope” to share with migrants, the pastor said.

The pilgrims met with evangelical and Catholic church groups and Panamanian government officials, and they visited Lajas Blancas migrant reception center, where migrants arrive, often hungry, injured, or exhausted, after crossing the Darien Gap. The Como Nacido Entre Nosotros delivered donations of food, clothing and personal hygiene items, as well as medical assistance and spiritual care.

Rodríguez said he was struck by the commitment of the Panamanian Christian young adults who woke up at 2 a.m. on a Saturday to fill two buses of donations and then drive more than five hours to the Darien Gap, where they served until late at night.

“In this country, we live a Christianity completely privileged, comfortable, and of cheap grace,” Rodríguez said of the U.S., where he has not seen a similar commitment by Christians.

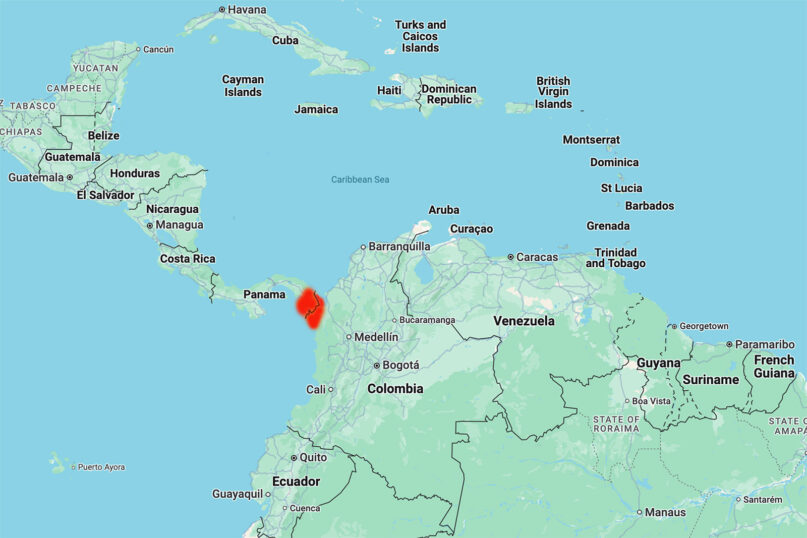

The Darien Gap, red, connects North and South America along the Panama-Colombia border. (Image courtesy Google Maps)

The Darien Gap, a jungle and marshland landscape covering a 60-mile break in the Pan-American Highway, is the only overland route connecting North and South America. Crossings through the Darien rose from an average of 2,400 crossings annually in the early 2010s to more than half a million people last year, as more migrants flee South America countries, such as Venezuela. Migrants through the jungle face criminal gangs, difficult terrain, and lack of cellphone service, clean water, and food.

Meeting the migrants also moved Rodríguez. “I am a man. I identify with the men who cannot provide for or protect their families, that type of powerlessness,” said Rodríguez, clarifying that the men are not physically powerless, but instead morally powerless.

Rodríguez was outraged by reports of sexual violence against migrant women on the journey — and by the “silence” and lack of action to address it. “As if it is something normal, that many migrant women are sexually abused on their journey, and no one does anything. There is total impunity.”

“My conscience does not allow me to get to the level of having to accept that as a given fact of the migration process,” Rodríguez said.

Ortiz said the migrants he spoke with were fleeing from personal experiences of violence, and many were hoping to reunite with family. In the camp, they met migrants from Latin America and Africa, including Congo and Cameroon, as well as Pakistan and Nepal.

He provided RNS with recordings of conversations he had with migrants in Lajas Blancas, where many repeatedly urged other migrants to avoid crossing the Darien Gap because of its danger, and some recommended against migrating altogether.

An Ecuadorian father named Carlos told Ortiz that “the voyage was extremely difficult,” mentioning hunger, as well as tigers and snakes in the jungle. He said that he had been tricked by his guides, who had not followed through on their promises, and that his wife had miscarried her pregnancy of two months.

Carlos also recounted jumping back in a river after his own crossing in order to rescue a family from drowning who had been swept away by a current.

Other migrants recounted losing people who had traveled with them or seeing dead bodies.

William, a 57-year-old migrant with infected wounds on his legs from a fall during the crossing, said the vast majority of people crossing the jungle suffered some kind of injury.

During their meeting with Panamanian authorities, Ortiz said, the Christian group learned that, while crossings of the Darien Gap have significantly dropped since their peak in 2023, the government believes it will run out of money to feed migrants in December. The Panamanian officials also shared that migrants leave over 2,000 tons of garbage in the jungle, which is a national park.

Ortiz also said that at the request of the Panamanian government officials, the pilgrims prayed for the soldiers during the camp visit and the trauma they experience in their work with migrants.

After conversations with local churches and the government, the network is looking for more ways to collaborate on humanitarian support and logistics. Instead of just welcoming migrants who arrive in the U.S., Ortiz said the idea is to “encounter the people on their journey and get to know them on their journey so that they feel accompanied by the church because the church is one no matter which country it is in.”

Looking ahead, the network hopes to plan more pilgrimages, especially in response to changes in government policy in the U.S., Panama, and Venezuela, because, regardless of policy, leaders of the network cannot imagine migration stopping.

“Migration is the crisis of the 21st century,” Ortiz said.

Malavé said, “As I deal with the new reality that we are experiencing in our country, the anti-immigrant sentiment, it is very powerful when you can look back and look at the faces of people, having heard their stories, and that motivates you to keep working and to not give up even though this scenario looks very grim and very difficult.”

Rodríguez said Christians have a choice between seeing migrants as angels or as criminals or “scum.”

Citing Matthew 25, Rodríguez said, “The decision that we take on how to see the migrant will be the material for our judgment in front of the Lord.”