(RNS) — In 1775, a year before there was a United States and six weeks after the Continental Army was formed, George Washington made a declaration that has shaped the military ever since.

“We need chaplains,” he reportedly remarked, prompting action by the Continental Congress near the start of the Revolutionary War.

Cmdr. John Logan, a Navy chaplain aboard the aircraft carrier USS George H.W. Bush, reads a prayer during a sunrise Easter service held on the flight deck. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 1st Class Sean Hurt/Released)

The U.S. military chaplaincy will mark 250 years on Tuesday (July 29), as the national military marked its own 250th anniversary in June. A week of celebrations includes a golf tournament at Fort Jackson in South Carolina, hosted by an organization raising funds for scholarships for family members of chaplains, and a sold-out ball nearby in Columbia. Meanwhile, across the globe, thousands of clergy in uniform continue to provide counsel and care to military members of a range of faiths or no faith.

“In times of peace and war, our chaplains have held fast as beacons of hope and resilience for our troops, whether enduring the brutal winter of Valley Forge, comforting the wounded and dying on the battlefields during the Civil War, braving trench warfare in World War I, storming the beaches of Normandy during World War II, marching the frozen mountains during the Korean War, slogging through the rice paddies and jungle battlefields of Vietnam or traveling the bomb-filled roads of Iraq and Afghanistan,” said retired Chaplain (Major General) Doug Carver, a former Army chief of chaplains in charge of the Southern Baptist Convention’s chaplaincy ministries, at the denomination’s June annual meeting in Dallas.

A month later at the annual session of the Progressive National Baptist Convention in Chicago, Navy Chaplain J.M. Smith, the grandson of a former PNBC president, stood before delegates and described his just-completed tour as a Marine Corps command chaplain in Okinawa, Japan, and his plans to report to a ship in Norfolk, Virginia, to begin a tour of Europe and the Middle East and be promoted to lieutenant commander.

“My team and I have ministered to thousands of Marines, sailors, civilians, and Japanese,” he said. “We increased our chapel’s membership from eight to 100. We incorporated spiritual readiness into our base’s core curriculum.’’

Chaplains serve in hospitals, hospices, and manufacturing plants, and while chaplaincy researchers see commonalities among them, there are also key differences in the military. All are involved in gaining the trust of people who are in their particular milieu, enabling them to think and sometimes pray through their times of greatest need and day-to-day struggles.

An example of both the danger and the dedication of military service chaplaincy is the 1943 death of four chaplains — two Protestant, one Catholic, and one Jewish — who helped save some of those aboard a World War II ship, turning over their life jackets and praying and singing hymns before it sank. All four were trained at Harvard University, then the site of the Army’s chaplain training school, during a two-year wartime period.

“It was a real defining moment,” said retired Gen. Steve Schaick, who served as Air Force chief of chaplains from 2018 to 2021, and in the same role for the Space Force from 2019 to 2021. “The stories that came from that really kind of highlighted chaplains at their best.”

The Army’s chaplaincy corps also includes religious affairs specialists and religious education directors. Some service members provide armed protection to unarmed chaplains and set up worship spaces in on-base chapels or makeshift altars on truck hoods in the field. For example, Berry Gordy, who later founded Motown Records, served as a private in the Korean War and played a portable organ and was known as a chaplain assistant, notes “Sacred Duty,” a new comic book posted on the Army’s website to mark the anniversary.

While 218 chaplains served in the Revolutionary War, 9,117 chaplains served in World War II, according to the Army. Currently, the Army has 1,500 chaplains on active duty. The Navy Chaplain Corps, which began on Nov. 18, 1775, had 24 chaplains during the Civil War; 203 by the end of World War I; 1,158 at its height in 1990; and currently has 898 on active duty, according to the Navy.

“Today’s Chaplain Corps includes Chaplains representing a multitude of faith groups, and the Chaplain Corps recruiting team is actively working to increase the Corps’ diversity, with a special focus on increasing the number of women Chaplains in the Corps and the number of Chaplains representing low-density faith groups,” reads an Army historical booklet marking the Chaplain Corps’ 250 years.

Initially, U.S. military chaplains were Protestants. The first Catholic chaplains served in the Mexican-American War in 1846, and the first rabbi was commissioned in 1862 and served in the Civil War. The first Muslim chaplains were commissioned in the Army in 1993. The first Buddhist Army chaplain was named in 2008, followed by the first Hindu chaplain in 2011.

Chaplain Margaret Kibben, acting chaplain of the House of Representatives and former chief of chaplains of the Navy — the first woman in that role — said the isolation and the immediacy of ethical decisions faced by military members, as well as a high level of confidentially, can make the work of military chaplaincy teams different from other settings where chaplains work.

“It’s the one place that people can go where there’s essentially a sanctuary around them, wherever they find themselves, a safe place to have somebody to talk to about a whole host of issues,” she said, adding that topics can include anything from supporting their families to handling combat responsibilities. “How do you deal with those issues in a place where you’re not going to look stupid, you’re not going to look weak or unreliable because you have these doubts and you have these concerns — to have a place that you can go to ensure that you can get that off your chest?”

Those private conversations often are not faith-filled, added Kibben, reflecting on her military career that began in 1986.

“What I realized later, 20, 30 years later, was that many service members have never learned the language of faith,” she said, citing terms like confession and forgiveness. “So as a chaplain, we had to figure out our way around the lack of a lexicon of faith. How do you speak about grace to someone who doesn’t have a clue how powerful grace is?”

Another change, sparked by the efforts of Julie Moore, the wife of a military officer who served in the Vietnam War, was the Army’s method for notifying the next of kin when a soldier died. Soon after a 1960s battle in that war, a chaplain and a uniformed officer began teaming up to knock on families’ doors; prior to that time, the news arrived in a telegram delivered by a cab driver.

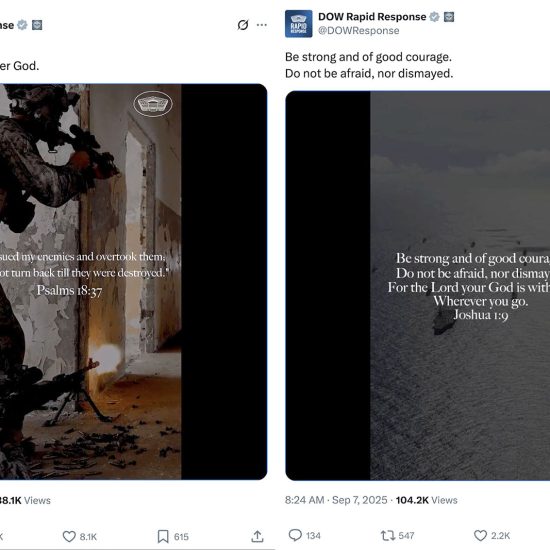

The work of chaplains has sometimes been the source of church-state debates. For example, Michael “Mikey” Weinstein of the Military Religious Freedom Foundation, a nonprofit that advocates for separation of church and state in the U.S. military, has questioned what he viewed as proselytism in the chaplains’ ranks. Meanwhile, conservative Christian organizations have voiced concerns about an antipathy against some Christians in military ranks.

Karen Diefendorf, a two-time Army chaplain and a board member of the U.S. Army Chaplain Corps Regimental Association, which supports chaplains and their families, said the primary goal for chaplains is “to provide for the free exercise rights of every soldier, sailor, airman, Marine, Coast Guardsman.” She currently is an interim minister of an independent Methodist church in South Carolina, after serving as a chaplain at Tysons Foods and in hospice care.

“I had soldiers who were practitioners of Wiccan faith, and my job is not to say to them, ‘Hey, wouldn’t you like to love Jesus?’” she said, recalling how she assisted a Wiccan Army member serving in Korea. “My job was to help that young soldier find where his particular group of folks met and where he could practice his faith.”

Also during her service in Korea in the late 1990s and early 2000s, Diefendorf said she provided cassette tapes of sermons to soldiers and entrusted one with Communion elements because she knew she wouldn’t be able to reach their location often.

“So far, the courts have upheld that you certainly have two competing clauses within the First Amendment, establishment and free exercise,” she said. “And at this point, certainly chaplains have to walk that fine line not to create establishment in the midst of trying to also enable people to practice their beliefs.”

Schaick recalled being deployed overseas in the Air Force when a new rabbi joined his staff. On arrival, the rabbi described himself as “first and foremost a chaplain and secondarily a rabbi” — an order of priorities that Schaick said applies to chaplains to this day, regardless of their faith perspective.

“The longer you serve in the chaplaincy, I think the closer you get to really believing that — and therefore, religious affiliation becomes secondary,” he said. “It’s ‘How’re you doing today?’ and ‘I’d love to hear what’s on your heart’ and ‘How can I be able to help you today?’ Those kind of questions, quite frankly, are impervious to religious distinctions.”