ASHEVILLE, N.C. (ABP) — Dynamite pulling down mountain tops and satellite dishes pulling down a homogenizing signal are making Appalachia as a clearly defined region disappear before our eyes, according to longtime Appalachian watcher, minister and historian Bill Leonard.

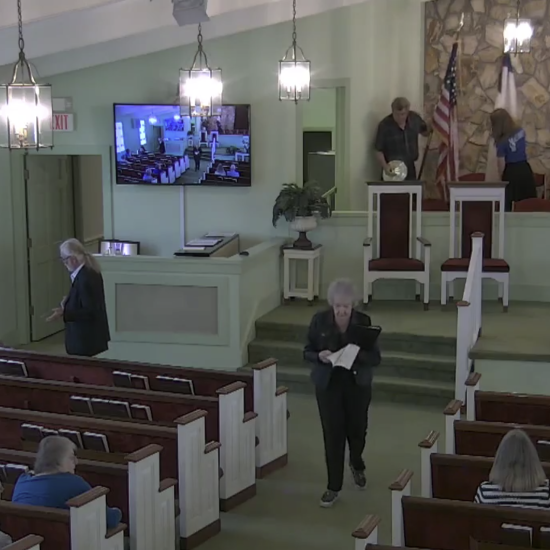

"Mass culture is overtaking it," Leonard said during a breakout session at the 2011 annual meeting of the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship March 25 at First Baptist Church in Asheville, N.C.

Technology penetrates the isolation that gave Appalachian families, churches and cultures its distinctive lilt. Now 24/7 "virtual religion" flows down the crease of every holler, streaming into trailers and cabins from sources as disparate as the prosperity gospel of TD Jakes and Mike Murdoch, the sweet Catholic piety of Mother Angelica, the strange new perspective of Mormons, the ubiquitous presence of the Gaithers music and Joel Osteen "insisting God feels good about himself and you should too."

"No single force is changing Appalachian church life like the technology of televised religions," said Leonard, who is on sabbatical as professor of church history from Wake Forest University School of Divinity.

Leonard addressed the changing Appalachians because the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship and other denominational groups are targeting the region with social ministries they expect will lead to spiritual development. Appalachia is a 1,600-mile long belt of mountains in eastern North America that stretches southwest from the Gaspé Peninsula in Quebec Gulf coastal plain in Alabama. Mount Mitchell (6,684 ft) in North Carolina's Black Mountains, just a few miles from where Leonard was speaking, is the highest peak.

They currently, but less frequently, find distinctive branches of faithful in the mountains, such as "No Hellers," who are Primitive Baptist Universalists of no more than 1,000 members in 20 counties. They "press their Calvinism to the logical conclusion — or illogical — that Christ's redemption is so powerful that all will be redeemed," Leonard said. They believe, "It's hell enough down here."

You will also find Pentecostal Holiness and those who will handle snakes and drink poison, pressing the literalism of Jesus' words in Mark 16:18. Disagreements will surface between Trinitarian and "Jesus only" theology. Leonard said denominationally connected churches, both in rural areas and in town, thrived in Appalachia, "holding to a fundamentalism that paralleled mountain sectarians."

King James remains the only "orthodox text" Leonard said, as he told of one pastor relating a conflict in an associational meeting because "one of the young preachers stood up and announced he was NIV positive."

More than any other distinctive religious expression, mountain religion is tied to oral tradition, the centrality of religious experience and the reality of the land," Leonard said, quoting Appalachian observer and writer Deborah McCauley

The elements that give the Appalachian region is distinctiveness are being hit hard by demographics, culture and destruction of the very mountains that gave the religion its uniqueness.

In the cultural dilution, Appalachia is not immune from the "mega-churching of America," Leonard said. Such churches "may be doing for Appalachian ecclesiology what Wal-Mart did for customer service. They rise on the edge of town, draining the life from mom and pop churches."

The mega churches, along with virtual religions pumped into living rooms from satellite dishes, are changing the expectations of church members for what preaching, worship, music and evangelism should be like, he said. On the other hand, these large churches also often provide meaningful activities for aimless and unemployed youth.

Evangelicals are immune to the backlash of that change prompts. Leonard said an attempted book burning by Amazing Grace Baptist Church in Canton, N.C., targeted writers and musicians like Rick Warren, Charles Colson, Billy and Franklin Graham and the Gaithers.

But, in good Appalachian fashion, the church advertised that after the book burning they would be serving fried chicken with all the sides.

A small but increasing presence of non-Christian religions is rising to give the mountains a global flavor. Leonard sees storefront signs alerting locals to the presence of the Islamic Society, Eckankar meditation, yoga and Wiccan practitioners. Buddhists, Muslims or Hindus run mom and pop motels throughout the region.

Environmental tragedies plague the region as forests disappear, mountain tops are blown off and creeks fill with the sludge of open pit mining. With few exceptions, Leonard said, the benefits promised to gain acquiescence for the destructive practices never materialize and the powerless populace is left with barren plateaus, poisoned water and disappearing culture.

"Large pieces of religious culture are coming apart," Leonard said.

As an observer who has watched Appalachian distinctives crumble away over decades, Leonard said it is important to remember Appalachia before it disappears. He said the mountain churches "reflect the strength and danger of sacraments and symbols."

Mountain religion can be dangerous, he said. River baptisms "can kill you" if you're swept away by the frigid, fast moving water. Wine is dangerous, whether purchased at Wal-Mart or poured from a backyard source; foot washing is dangerous relationally because it is difficult "to have ought against your brother or sister who is washing your feet.

Serpent handlers taught Leonard that "sacrament is alive, and it can kill you. Every time you go to worship it is a matter of life and death. That's fascinating to me."

"Generally speaking, Appalachian mountain churches refuse to civilize, memorialize or intellectualize the life out of the means of grace," he said.

Such churches also demonstrate the power of oral tradition and the strength of story. While mountain preachers may seem semi-literate to pedigreed flatlanders, some have committed large amounts of scripture to memory and have "amazing pulpit skills."

Appalachian religious communities embody an ability to acknowledge "sacred space" Leonard said, "and reclaim it when lost."

But as strip mines and strip malls, slag pits and condo complexes, polluted rivers and manhandled mountains mark the Appalachians, those sacred spaces are washing down the mountains like so much sludge.

"If Jesus continues to tarry and the mountains continue to vanish and the Church on Earth remains asleep then somebody ought to try and wake it up," Leonard said. "Before we all have to learn to sing the Lord's song in a treeless and mountain less land."

-30-

Norman Jameson is reporting and coordinating special projects for ABP on an interim basis. He is former editor of the North Carolina Biblical Recorder.