ATLANTA (ABP) – The American Civil War affected Baptists in the South in profound ways that still reverberate more than 150 years after the first shots were fired on Fort Sumter, says a new book by a Baptist historian.

"Diverging Loyalties: Baptists in Middle Georgia During the Civil War" is published by Mercer University Press.

|

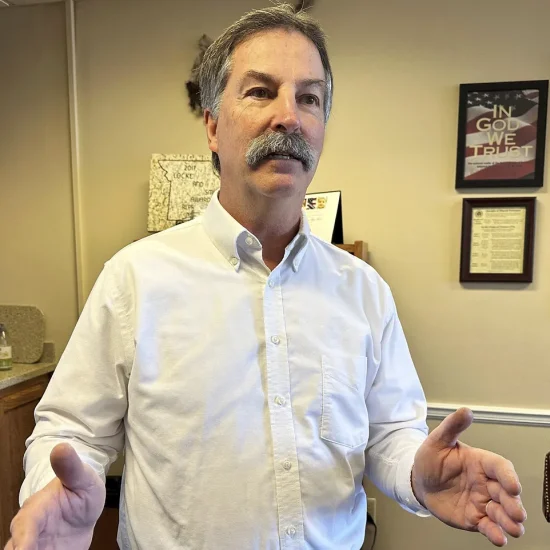

Author Bruce Gourley says in Diverging Loyalties: Baptists in Middle Georgia During the Civil War that the Calvinism that caused many Baptists to view the war as God’s providential hand guiding the Southern cause waned as early victories turned to defeat and all but disappeared from public discourse by the turn of the 20th century.

Gourley, executive director of the Baptist History and Heritage Society, said that silence was not because of disinterest in the tenets of Calvinist theology, but rather integration of ideas of providence and sovereignty with a heightened embrace of free will prompted by the global spread of human progress, democracy and freedom following the war.

Gourley says it wasn’t until the cultural and social revolutions of the 1960s and 1970s, followed by fundamentalist-modernist struggles in the Southern Baptist Convention, that Calvinism made its comeback.

“Some conservatives of the late 20th century, spearheaded by the Calvinistically reoriented Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, appropriated the language of providence from Baptist life of the 1850s and 1860s in an effort to legitimize their current cultural positions and seek purity of theology,” Gourley observes.

Along with challenges to theology, Gourley says, the war set back the trajectory of Southern Baptist missions. Not until the 1880s did Southern Baptist missionary activity experience notable recovery, and it was thanks to the efforts of women.

“Although yet regulated to traditional roles of limited power within local churches, women experienced increased numerical influence within church life after the Civil War,” Gourley writes. “Seizing an initiative that men failed to address adequately, women in the 1880s used their numerical clout to develop funding mechanisms for missionaries at home and abroad.”

Gourley says women’s support not only remains critical to the success of Baptist mission work, but their influence on the mission field opened doors to other formal leadership roles for women, including pastoral positions, despite resistance from denominational leaders.

By the time of the Civil War, Gourley says Baptists in the South had long welcomed slaves into their churches, accepting responsibility for their souls if not their bodies. Refusing to accept blacks on the same level as white Europeans, Southern Baptists joined other Christians in the South equating the African race with the descendants of Noah’s son Ham, cursed to subservient status in the book of Genesis.

With increased racial tensions during Reconstruction, many black freedmen abandoned white power structures to establish their own missionary and educational structures. Freed from white paternalism, black Baptists continued to experience growth even after Southern Baptists peaked in the 1950s. Southern Baptist efforts to recruit black members in the latter decades of the 20th century, Gourley says “produced limited success.”

“While most Baptist congregations yet remain segregated, as they were in the years immediately following the war, African-American Baptists today are arguably more influential than Southern Baptists in the South, reflecting a juxtaposition of the racial dynamics of Civil-War era Baptists,” he observes.

-30-

Bob Allen is managing editor of Associated Baptist Press.

Diverging Loyalties: Baptists in Middle Georgia During the Civil War is published by Mercer University Press.