Contemplative worship — with its emphasis on prayer and reading that leads participants into a silent, meditative encounter with God — pushes some Baptists outside their comfort zone.

But the increasingly popular approach sits comfortably with historic Baptist values, according to several advocates of this ancient worship style.

|

"Contemplative worship is consistent with Baptist tradition, and it can enrich and enhance that tradition,” said Randy Ashcraft, pastor in residence at the Virginia Baptist Mission Board.

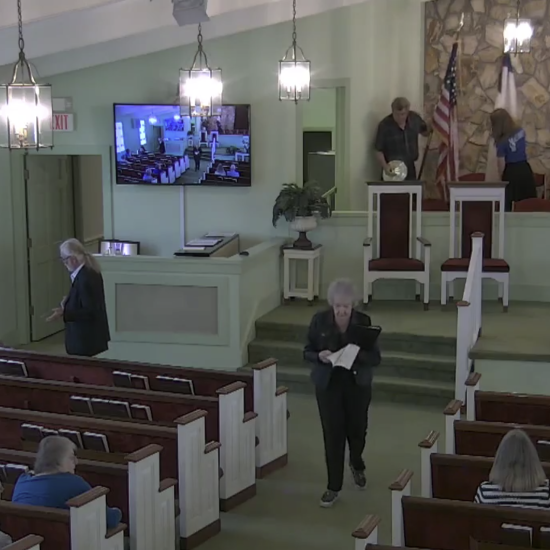

As part of his assignment to foster spiritual formation among Baptists in Virginia, Ashcraft regularly employs contemplative spiritual practices — most recently at a weekend retreat in Richmond that drew dozens and culminated in silent, meditative worship.

Baptist values such as the priesthood of the believer, the centrality of Jesus and a desire to be truly connected to God “all find a home easily in the contemplative worship tradition,” Ashcraft said.

In Waco, Texas, the pastor of DaySpring Baptist Church finds similar convergences.

“Baptists are people who have consistently desired personal connection with God, and the nature of the contemplative life is very much that God may be encountered personally,” said Pastor Eric Howell, whose congregation describes itself as “a Baptist church in the contemplative tradition.”

“Another consistency is the belief that God is actually present and active in the worship service, and in the lives and hearts of the worshippers, in a way that is not ultimately dependent on what happens from the microphone. Contemplative worship affirms the congregation’s participation in worship at the deepest level.”

Both Ashcraft and Howell say the doctrine of the priesthood of the believer — the quintessential Baptist insistence on humanity’s direct access to God through Jesus — makes contemplative worship a compelling spiritual exercise for Baptists.

Michael Sciretti, minister of spiritual formation at Freemason Street Baptist Church in Norfolk, Va., shares that view. He calls the “unmediated experience of God” one of the root images of Christian spirituality.

“We need to reclaim the language of priesthood and that all of us are priests,” said Sciretti. “To say we are a priest means we have ‘temple’ duties and functions. [The Apostle] Paul teaches that the Christian is a temple of the Holy Spirit, and the Jewish temple had chambers, the preeminent chamber being the Holy of Holies.

“Therefore, contemplative worship — or ‘con-templing’ worship — is about going into the innermost chamber to experience and encounter God in our own hearts.”

Sciretti developed that idea in a book, Entempling: Baptist Wisdom for Contemplative Prayer, that he edited with Blake Burleson, associate dean for undergraduate studies at Baylor University’s College of Arts and Sciences. The book is a compilation of writings by four centuries of Baptists, both well-known and obscure.

“The historical Baptist focus on experience with and relationship to the Divine Presence provides an important foundational element for contemplative prayer, meditation and worship,” said Burleson. “It is necessary for the contemplative [worshiper] to bring his or her presence into the Divine Presence.”

The “unmediated experience” is deeply rooted in the Baptist experience, said Bill Leonard, professor of Baptist studies and church history at Wake Forest University School of Divinity.

“The idea of the direct encounter of each individual with God through Christ lends itself to times of reflection, prayer and contemplative worship,” said Leonard. “One need only read [John] Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress to recognize the spirituality emphasized by 17-century Baptists.”

But, Leonard added, an inclination among Baptists in the American South toward evangelistic action — doing rather than being — probably diminished the value of contemplative worship in their eyes.

“Baptist emphasis on immediate Christian (evangelistic) activism has tended to minimize the sense of the contemplative in much of Baptist spirituality,” he said. “When I have taken Baptist students to monasteries, they always ask, ‘What are these monks doing to express their Christian witness?’ The monks explain that their life is their witness.”

Howell noted that practicing silence is foreign to some Baptists — especially silence that is something other than “a prelude to what is really happening or silence as an indication that someone forgot their part.”

“At the heart of contemplative worship is the silence between words,” he said. “This can feel contradictory to a tradition that emphasizes the spoken and proclaimed Word. I see this as complementary, but someone unfamiliar with this approach to worship might be thrown off.”

But Ashcraft said that “contradiction” can be bridged.

“When I was growing up, everyone was encouraged to have a ‘quiet time’ intended to be an opportunity to be nurtured by Scripture, to listen to the voice of God, to respond to that voice, to engage in confession and, hopefully, to sense God’s purpose for one’s life,” he said. “That essentially describes the tradition of lectio divina” — an ancient Christian contemplative practice of Scripture reading, meditation and prayer.

Reclaiming that tradition in part motivated the Virginia Spirituality Institute, being developed by Ashcraft and Sciretti, along with two Richmond pastors, Drexel Rayford and Sammy Williams.

“Our aim is to be a resource, to provide education and opportunities for Baptists in Virginia and elsewhere to sense the fresh winds from contemplative worship,” he said. “We have found that it is rejuvenative and builds hope in the lives of individuals who sit in congregations each week.”

Howell offered a warning for Baptist churches exploring contemplative worship.

“Please don’t make ‘contemplative’ the next brand or style of worship,” he said. “While we have discovered many young people hungering for the expression of worship and faith that we practice, churches need to understand the contemplative life is not a strategy to reach ‘emergent young people.’ It’s a way of life and posture toward God that may or may not attract people.

“The utility of the worship service becomes secondary to the encounter with the living God that happens when people slow down and listen and trust themselves and one another in God’s presence.”

Robert Dilday (rdilday@religiousherald.org) is managing editor of the Religious Herald.