AMMAN, Jordan — Sitting on cushions in an almost bare apartment in a crowded Palestinian neighborhood in Amman, Jordan, a family of Syrian refugees began to tell their story through an interpreter to a pair of visiting Baptist journalists from America.

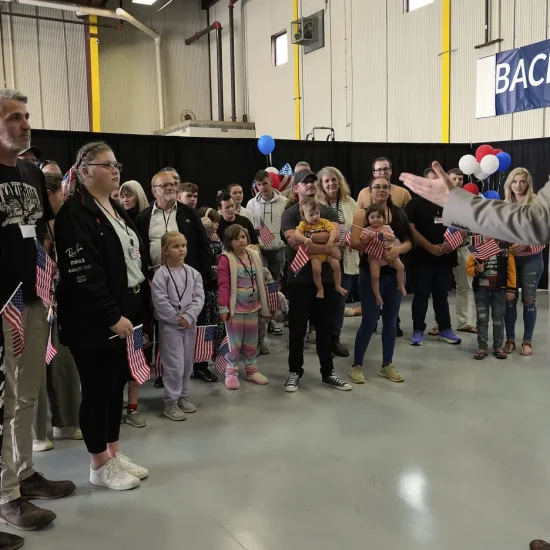

Adult Syrian refugees cover their faces for a photograph because they have relatives still in Syria and choose to remain anonymous when portrayed in media to protect loved ones back home. Syrians have flocked to Jordan to escape the civil war engulfing their native land.

|

The unannounced visit interrupted a day of housecleaning, but the visitors were welcomed with little hesitation. They wanted to hear the story of this family’s experiences during the Syrian civil war and their exodus to find refuge in this ancient capital city in the nation immediately south of Syria.

They briefly described their life in Syria as farmers on fertile that produced crops like barley, tomatoes and potatoes in good supply. Theirs was a good life, and they had been happy there.

But the good life disappeared. The people living in the area were soon surrounded by government forces commanded by Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, and supplies were cut off. The family’s teenage daughter demonstrated how troops intentionally trampled the crops, cutting off residents’ food supply.

The family fled to Jordan several months ago.

The family’s 14-year-old son described the chilling experience on June 1, 2012, when soldiers opened fire and bullets struck him in the leg and tore through the tendon of his then 6-year-old brother’s leg behind the knee. The older brother had thrown himself onto his younger sibling to protect him from further harm.

The driver of a car in the vicinity also was hit. In trying to get away during the shooting, he ran over the older boy’s leg, breaking it in three places.

The 7-year-old still has not had his tendon repaired. After school, he showed the journalists his scars and a crude brace that enables him to lift his foot as he walks.

His family still hopes the time will come when the youngster can have the needed surgery, but any money the family can earn goes first to pay their monthly rent (nearly $150) and then to buy food for the family. Their landlord threatens to evict them if they don’t pay on time. UNICEF provides food stamps to help with food.

The influx of about a half-million Syrian refugees into Jordan — a third in refugee camps but two-thirds scattered among the general population — guarantees a steady housing market. Refugees claim many landlords raise their rates for refugee families.

As the conversation continued, upstairs neighbors came in and more floor cushions appeared. The intensity of the stories increased, too, as each person recalled his/her pain and losses. In some cases, the tone was angry.

An older couple described their own losses — two sons.

“One of my sons was in the police,” the woman said, “But when he was told to kill some people who had done nothing wrong, he said he could not do it. A while later, they executed him. They put a gun to his head and killed him.”

The other son, they explained, died in an air strike as he prayed in a mosque.

The teenage daughter and others took issue with casualty numbers reported from recent chemical weapons attacks that turned out to be in the area where this family had lived. Said the girl: “We heard what they said on television, that 1,400 people died in the gas attacks. It was more than that — many more!” She charged that government forces scented the gas with hibiscus to disguise its deadly odor.

A middle-aged woman from upstairs heatedly joined the resulting discussion, repeating a concern shared by all present. President Obama had disappointed the refugees, she said. Their only hope of returning home was a U.S. strike that would have eliminated the Syrian president.

As long as Assad remains in power, they will continue to be refugees, they said.

The woman had fled Syria but her husband is still there. The family could not afford to pay for him to get out. Asked how much would be required, she shrugged, “It depends on how much money someone wants that day.”

Her voice raised and she became even more animated as she seemed to address Obama: “You know about the chemical weapons, and still do nothing! We are out of hope!”

Winter is coming and the clothes on their back are the only ones the refugees have, she lamented.

A short distance away, another family opened their apartment to share their story. This was a younger couple with a 10-year-old daughter and a 6-year-old son.

They recalled ongoing government airstrikes every night back in Syria as the family huddled under thin foam mats, fearful and unable to sleep. The woman has nine siblings still back in Syria, including a brother who is a medical doctor who disappeared months ago and is still missing. Her husband’s parents remain in Syria.

They left their home and moved in with another family in Syria before a bomb destroyed their home. To protect their children, they fled.

The father works when he can find it but sometimes is shorted when he is paid. He has no recourse. Despite applying for a passport in Syria years earlier, one was never granted, the process further delayed by the war. This makes him an illegal in Jordan, without legal recourse when disputes over promised wages occur.

He said he wants Americans to know that the desire for basic human freedom is what made Syrians revolt against Assad.

His wife says she became physically sick when she learned that the U.S. was not going to bomb Syria. That was their only hope of returning home and rebuilding their lives and home, she said.

Their daughter still dreams of becoming either a medical doctor or a pharmacist some day, while the 6-year-old misses riding the bicycle he left behind when his family fled Syria.

Editor Bill Webb and Jim White, editor of Virginia’s Religious Herald, recently visited Jordan. The fear of retaliation against loved ones in Syria prompted them to withhold names and to refrain from showing the faces of adults in photography.