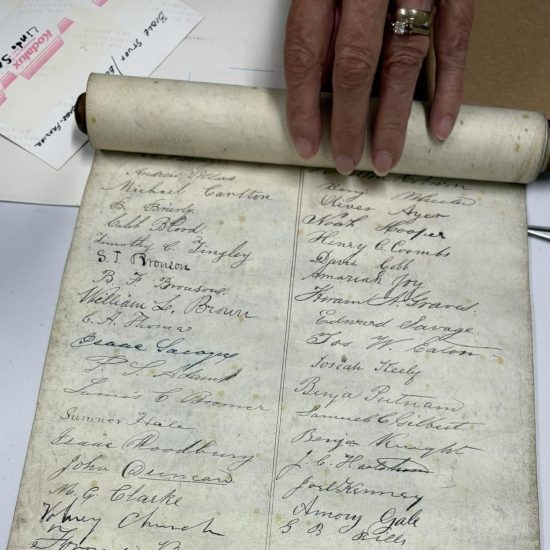

When Baptists constituted a minority sect in America, bold spokesmen such as John Clarke, Obadiah Holmes and James Ireland took courageous stands for religious liberty, historians agree. Baptists like John Leland led in calling for separation of church and state and demanding liberty of conscience for all people.

But in communities where Baptists and other evangelicals predominate, do their modern spiritual descendants demonstrate the same commitment to speaking up for religious minorities?

What does religious liberty mean in today’s culture?

|

When the shoe is on the other foot, are Baptists willing to speak up for nonbelievers or followers of non-Christian religions who object to religious displays on government property?

When they do, it can be a lonely place, said Brad Bull, whose opposition to a Ten Commandments display in Knox County, Tenn., set off a firestorm locally more than a dozen years ago. At the time, Bull served as associate pastor of youth and young adults at Cumberland Baptist Church in Knoxville.

Originally, he attended a public hearing regarding a resolution to authorize prominent placement of the Ten Commandments at the courthouse just to monitor the situation. Prior to the meeting, he privately expressed his concerns to a county commissioner, who later unexpectedly called on him to speak to the issue.

“I was motivated by what I learned in seminary and from my reading of Baptist history. Beyond that, it’s like I told a county commissioner at the time: ‘I have a neighbor who is Buddhist. Another neighbor is Muslim. They pay taxes in the county just like I do.’ I just saw what I did as an issue of fairness,” Bull said.

He never anticipated the fallout. After the Knoxville newspaper and a local radio station reported his opposition to the resolution, his wife, Connie, nearly lost her job teaching Spanish and music as part of a cooperative for home-school students.

After the parents of a couple of her students objected to her husband’s comments, the church where she taught classes threatened to cease making its facility available. The cooperative placed her on leave for two weeks until the matter could be resolved.

After a three-hour meeting in which Bull fielded questions about his theology and his politics, all the parties finally agreed to disagree about the Ten Commandments display. A few days later, the Bulls joined several individuals involved in that meeting for dinner after a Christmas concert.

Looking back, Bull said, he not only felt he “went out on a limb” where many fellow Baptists failed to join him, but also believed some Baptists in the community were “shaking the tree.”

“I don’t have any regrets about the stand I took. My regret is for Baptists in general,” Bull said. “There’s a lot of lip service paid to separation of church and state and a lot of lip service offered to sacrifice, but there’s a whole lot of hypocrisy, myself included. That saddens me.”

Baptists need to honor their heritage by standing for religious liberty — and the principle of church-state separation that protects freedom of religion, said Courtney Krueger, pastor of First Baptist Church in Pendleton, S.C.

“As a Baptist Christian, I believe that we Baptists have a heritage and, therefore, a responsibility of promoting the separation of church and state,” Krueger said. “We must remind ourselves and others that inappropriate entanglements between church and state tend to harm both.”

In 2011, the Wisconsin-based Freedom from Religion Foundation responded to a complaint by an anonymous resident of Henderson County in Texas, and called on commissioners to remove a nativity scene from the courthouse lawn in Athens. The nativity was part of a display by Keep Athens Beautiful, and it included secular holiday scenes.

Some East Texas Christians joined a public rally supporting the nativity display, but Baptists among them voiced varied reasons for the support they offered.

Nathan Lorick, pastor of First Baptist Church in Malakoff, insisted he wanted to protect his children from an increasingly secularized society that marginalizes or vilifies Christianity.

He questioned how one local resident and an organization across the country could compel an East Texas county to reverse a longstanding tradition — particularly, he said, when evangelical Christians have a strong presence in Henderson County.

Kyle Henderson, pastor of First Baptist Church in Athens, posted a statement on his church’s website framing the issue in terms of free speech, and emphasizing the need to stand in support of unpopular minority voices.

Too often, Baptists and other Christians respond reflexively and allow partisan political rhetoric to shape their responses to complex issues, rather than thinking critically about them, Krueger observed.

“I do wonder if a response would not be to ask that any using such rhetoric apply the Golden Rule to whatever situation or issue they are commenting on,” he suggested.

Brent Walker, executive director of the Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty, echoed the sentiment. “Not everything is either barred by the establishment clause or required by the free exercise clause. Both clauses need to be taken seriously, but not so rigorously that one swallows up the other,” Walker said.

“We should always look out for the rights of the minorities — majorities can generally take care of themselves — and keep the Golden Rule in mind, a completely fair and evenhanded principle that all citizens should be able to rally around.”